Watershed Discipleship: Re-Imagining Ecological Theology and Practice

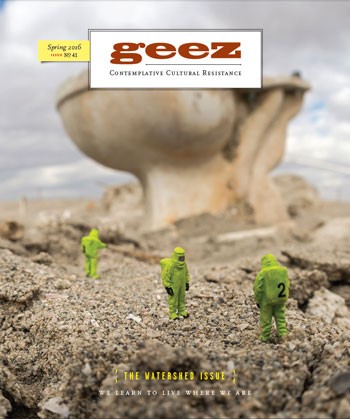

Pitt River Watershed in British Columbia. Credit: Simon Fraser University, https://flic.kr/p/oW8Cpf

An old-growth forest, a mountain range, or a river valley is more important and certainly more lovable than any country will ever be. – Arundhati Roy

Climate catastrophe and its interlocking ecological crises make this clear ultimatum: we must urgently “turn things around” – the biblical verb is “repent” – if we are to survive. But this poses a challenge for activists, for we often have little to offer in the way of positive alternatives. We are usually opposing the forces pushing us into this cul-de-sac.

In the 1980s I learned an important lesson while working with Indigenous communities for self-determination in various parts of the world. I saw over and over again that the people most likely to sustain fierce, long-term resistance, even against great odds, are those who are deeply rooted in their place and identity. This is because they are ultimately struggling for a way of life, not just against one.

With the above ultimatum in mind, I first identified as a bioregionalist in a book that attempted to articulate a First-World theology and practice of discipleship. At the time, environmental concerns, or what they call “creation care,” were just dawning on churches and theologians, and few were in significant conversation with deep ecology. An exception was Kentucky farmer Wendell Berry, one of the foremost Christian voices addressing placelessness in North America.

More than a quarter century ago Berry was arguing – quite out of fashion – that “global thinking” was often a mere euphemism for an abstract anxiety or passion that is useless in the struggle to save real places. “The question that must be addressed,” he contended, “is not how to care for the planet, but how to care for each of the planet’s millions of human and natural neighbourhoods, each of its millions of small pieces and parcels of land.” Only love for specific places – what native Hawaiians call aloha ‘aina – can motivate us to struggle on their behalf.

The focus for Christian theology, spirituality, and politics in the 21st century needs to be “re-place-ment.” And bioregionalism is a practical paradigm that is radical yet constructive, contextual yet universal. Kirkpatrick Sale’s 1985 primer Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision provides a helpful definition: “Bio is from the Greek word for forms of life . . . and region is from the Latin regere, territory to be ruled. . . . They convey together a life-territory, a place defined by its life forms, its topography and its biota, rather than by human dictates; a region governed by nature, not legislature. And if the concept initially strikes us as strange, that may perhaps only be a measure of how distant we have become from the wisdom it conveys.”

More recently, many bioregionalists, myself included, have emphasized an even more specific locus for re-inhabitory literacy and engagement based on what is most basic to life: water. Wherever we reside – city, suburb, or rural area – our place is deeply intertwined within a larger system called a watershed, which John Wesley Powell (the first non-Indigenous person to run the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in 1869) defined as “that area of land, a bounded hydrologic system, within which all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they become part of the community.” All of us live in a watershed, no matter how ignorant we may be about it (which most of us are). It is there we must take our stand.

A talk in 2009 by Brock Dolman, a permaculturist in Northern California, really sold me. “Watersheds underlie all human endeavors and form the foundation for all future aspirations and survival. The idea is one of a cradle,” he said, cupping his hands into a little boat. “Your home basin of relations is your lifeboat.” “Our watershed represents a community,” he continued, “every living organism within this basin is interconnected and interdependent.” This represents the most viable “geographic scale of applied sustainability, which must be regenerative because we desperately are in need of making up for lost time.”

What would it mean for Christians to re-centre our citizen-identity in the topography of Creation, rather than in the political geography of dominant cultural ideation, and ground our discipleship practices in the watersheds in which we reside? Five years ago I began to explore an approach I called “watershed discipleship” with other faith-rooted organizers and educators around North America. “Watershed discipleship” is an intentional triple entendre:

- recognizing that we are in a watershed moment of crisis. Environmental and social justice and sustainability need to be integral to everything we do as inhabitants of specific places;

- acknowledging the bioregional locus of an incarnational following of Jesus. Our discipleship and the life of the local church inescapably take place in a watershed context;

- and implying, as Todd Wynward added, that we need to be disciples of our watersheds, learning from and recovenanting with the local “Book of Creation.”

To paraphrase an argument made in 1968 by Senegalese environmentalist Baba Dioum, we won’t save places we don’t love; we can’t love places we don’t know; and we don’t know places we haven’t learned.

A symbiotic, relational ethos of watershed literacy and stewardship is crucial to the survival and flourishing of traditional societies. We have a long way to go to reconstruct such intimacy. Yet I believe this new/old paradigm holds the key to our future as a species, and can also inspire the next great renewal of a church that will squarely face the looming ecological endgame.

Re-placed ecclesial communities can make an enormous contribution to the wider struggle to reverse ecological catastrophe – and in the process recover the soul of our faith tradition. We Christians are deeply culpable in the present crisis, but we also have ancient resources for the deep shifts needed. Watershed disciples believe that only by “taking root downward,” as the old prophet Isaiah put it, “can the surviving remnant . . . again bear fruit upward” (Isaiah 37:31).

Ched is an activist theologian, popular educator, author, and advocate who has spent the last 35 years challenging and supporting Christians to engage in peace and justice work and radical discipleship. He is the editor of the forthcoming book, Watershed Discipleship: Inhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice (Cascade Books, 2016). He lives in the Ventura River Watershed in Oak View, California.

Note: For more information see watersheddiscipleship.org and facebook.com/groups/watersheddiscipleship.

U.S. readers can can locate their watersheds at cfpub.epa.gov/surf/locate/index.cfm.

Sorry, comments are closed.