Community is Bullshit

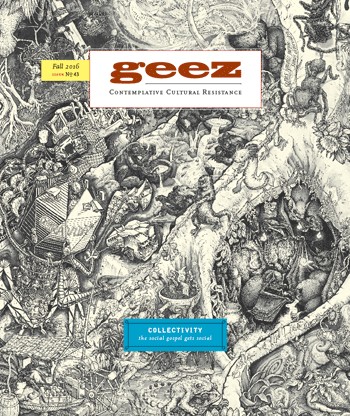

Credit: James Darling, https://flic.kr/p/8MvB4k

The following piece is rooted in my experience as a university student at the Oregon Extension, an intentional educational community based atop a mountain in Lincoln, Oregon.

The Oregon Extension was formed by a collective of independent Christian professors in the mid-1970s and grounded in the works of Thoreau, Dostoevsky, Annie Dillard, and Wendell Berry. It is known for its cultivation and examination of “big ideas,” and has been touted as a space for seekers of all stripes and disgruntled Christians alike. This article is an update of a story that originally appeared in catapult magazine [online] and in Road Journal magazine in 2008.

God, please help me not be an asshole, is about as common a prayer as I pray in my life. – Nadia Bolz-Weber, Pastrix

The year is 2001. Professor John casts his gaze across the batch of eager new students and, pausing for dramatic effect, calculates the measure of our idealism on some internal register built upon years of guiding sanguine undergrads. “Community is bullshit,” he grunts, turning away without explanation.

Twenty-year-old me is indignant. Had this professor, this Christian professor, really said what I thought he said? After countless months courting financial aid advisors, several hours on a plane, and interminable minutes inching along a mountain pass with the simple goal of sitting cross-legged on the floor of that room – a former logging camp cookhouse-turned campus library, a supposed mecca for pilgrims of my theological bent, a haven for skeptics and Jesus Freaks alike – I was in no mood for irony. I was there for community, damn it, and I expected these professors to dish it up as their pamphlets promised.

As it turns out, my professor’s words were prophetic. Though some of the best months of my life would be spent with these people, by the end of the semester my cabin had split, our little cadre disemboweled by petty arguments and arrogant presumption. One of my roommates moved in with her Mennonite-cum-postmodern-artist boyfriend; another retreated mysteriously into the forest with a sleeping bag and her unfinished novel, and a third invited her girlfriend to hunker down in the tiny bedroom adjacent to the kitchen, surfacing only for water and Discman batteries. By that time, our hoped-for utopia was a long-gone notion. We came with big dreams of common vats of hummus, late nights over yerba mate and clove cigarettes, and long hours spent dreading one another’s hair. These things did happen, don’t get me wrong, but a vat of hummus and a head of dreads does not a community make.

Of course, my experience is but one among many models of collective living. Not everyone who longs for community fetishizes hippie-era stereotypes of shared housing, common-pot economics, baking, batik-ing, and playing lute to throngs of naked toddlers and nursing moms. Yet, whether the collective is anchored in a shared ethos based in faith, social justice, or the simple practicality of geography, none are immune to the bullshit factor, as Professor John coined it, inherent in all human endeavours.

We, socialists and capitalists alike, are averse to acknowledging our own subjectivities. We make grand meals out of grass-fed beef and organic carrot cream soup, only to find that half at the table are vegan. We design houses fit for off-grid queens only to discover that Meadow enjoys a good 45-minute shower. We come together over shared ideals andfall apart over our own humanity.

These fissures are an innate part of any collective venture, and must be understood as the inevitable result of the interpersonal tectonics necessary for a community to function. That is to say, compromise and shift are required for any group to move from the realm of the theoretical into the realm of the real. If the individuals within the collective are willing to depart from their closely held notions of community, it then becomes possible (with actual, unsensational work) for the fissures to be transmogrified into ingredients for true, albeit wabi-sabi, community.

It’s been 15 years since Professor John grunted those iconoclastic words, and I have come to see their wisdom. In the meantime, I became a wife and a mother and have rubbed shoulders and greased elbows along the edges of several different ad-hoc collectives, though always managing to remain at a self-serving arm’s length from meaningful commitment.

Today, however, I had a first playdate with the wife of the local Baptist minister and her daughter. This may mean nothing on paper, but for me, consorting with two “mainstream” groups – “Moms Who Attend Playdates” and “Conservative Minsters’ Wives” – is akin to fetching my bra from the burn pile and tying an apron around my neck like a noose, fraternizing far from the margins in the burning hell of patriarchal normativity.

But, surprise surprise, if it wasn’t already evident in my diatribe, I was the asshole in the scenario. The Baptist-mom-hostess was genuine and generous, nothing feigned or forced. When I left I found that I was simply, startlingly, happy. The experience had been uncomplicated, comforting. In the same vein, after nearly 20 years of being unmoored from the institutional church, I have, in the past year, found a church community: I got religion. The structures of liturgy and playdates both, and the flesh and blood people these rituals are enacted through, are, for this cynical “spiritual but not religious” feminist, a necessary balm.

When I popped out my first kid, I lived in a city, had no community but for my former co-workers and grad school friends (all otherwise busy), and I found myself adrift, isolated, and in a really dark place. Now I live in a tiny town, and Baptist ministers’ wives are inviting me over for watermelon, despite my best attempts to look aloof and gnostic at preschool parent events. I am starting to come to the realization that though I think I don’t want community, to the marrow, I need it. And maybe that’s the kernel of wisdom, at least for me. Unintentional – and thus, perhaps, sustainable – community happens when the myopic vetting process for the people we’d like to commune with intentionally implodes from within, and we are left the humbled recipients of hospitality in unlikely places.

The point of origin for all communities – intentional and unintentional alike – hoping to defy statistics and remain viable in the long run may rest in the simple acknowledgement of our own humanity; which is to say, both our subjectivity and our capacity for change, our parallel tendencies toward destruction and creation.

When you see the Buddha of community in the street, as they say, you must kill it. Because, really, living in community is not about being happy, or safe, or a good steward – although if you are lucky, these things might happen in spite of you. Living in community does not make you better than your Trump-supporting, GMO-scarfing cousin, although it is likely to make you more judgmental. Living in community does not make you hipper, less morally repugnant, or more environmentally savvy, but it might make you feel exposed and vengeful and protective of your privacy.

So yeah, Professor John, you were right: community is bullshit. And as every community gardener knows, bullshit is beautiful. And now, I see, it’s my turn to till the soil. Lord help us all.

Katie Hoogendam lives in unintentional community in a little town on the shores of Lake Ontario. A former lone wolf, she is finding her way into various packs because without them, she will not survive her vulnerabilities.

1 Comment

Sorry, comments are closed.

Thanks, Katie, for your insightful essay. I lived in an intentional Christian social justice community for two years in my 20s. While I met some phenomenal people, I also met a few of the meanest people I’ve ever known to this day. I still marvel at the juxtaposition.

It is certainly understandable to become a lone wolf, and sometimes that just happens, like it or not. But we can’t get away from our need for community. And sometimes the best we can do is become someone who is good at it, yes, someone with soil fertile for growth.

Susan Harrison Portland, Oregon January 16th, 2017 8:53am