Editorial: We are Water, Let’s Swim

Credit: sherifx, https://flic.kr/p/qHbQ24

When I was young and evangelical, I had a summer job painting houses, and I didn’t care about the water table. I thought pollution was gum wrappers lying on the sidewalk. I also thought God would magically make everything better in the end. I really believed that.

When I got older, God came down to earth and dwelt among us and was in all things, and I started to care about the water table. But that was still a theoretical concern.

For example, one time when I was cycling to graduate school, I saw an odd yellow symbol on the pavement by a storm drain. Then I saw it again further down the road. It was the image of a fish, and it was “swimming” right by the storm drain. Something clicked. It seems weird to confess this, but until that moment I hadn’t connected my pouring poison down the drain with polluting the oceans and killing the fish. I thought that the city’s water system would magically make the poisons go away.

I have vague recollections of pouring terrible things down the drain: paint thinner from an odd job, a tub of gasoline after cleaning a bike chain.

If I became a powerful capitalist, and I kept the same theology of my youth, I could easily run a factory and pour toxic effluent into the sea; I could easily blast crap-loads of water under the earth, releasing oil from the goopy sand. All that would keep me from this would be the laws of the land, the threat of legal action, and financial loss.

But my religious worldview took a mystical turn. The transcendent God became immanent. Not pantheism, but panentheisim (a term I learned from Matthew Fox and his notion of creation-centred spirituality in his book Original Blessing). God is not all things; rather, God is present in all things.

How did I know God was in all things? Quite simply, I felt it. When I was baptized by the sprinkling of water over my 18-year-old head, I didn’t feel a mystical thing. I felt a sense of duty to a community. It was good, but theoretical. But when I smelled the towering cedars at summer camp, felt the plush padding of a path made soft by generations of needles falling to the forest floor, I felt it, I smelled it, I breathed it, and I was consoled by the vitality of a community of trees. Unconsciously, I knew that I was part of a meta-vitality that permeates everything.

Change happens slowly. It takes years, more likely decades, to develop new habits. Trial experiments can become new patterns of behaviour, more sustainable lifestyles.

This change can appear to others as insignificant: eating less meat to preserve water, travelling by bike to reduce fossil-fueled transportation, counting birds to appreciate vulnerable creatures and document species loss. These could be viewed as bourgeois activities, pastimes of the leisure class.

But, animated by a deep connection to the vital energy in and around us, i.e., a panentheistic worldview, these actions become seeds of subversion. We loosen our attachments to material goods, connect with people, respect our watersheds, and develop the fortitude to resist the exploitative, polluting patterns of the dominant culture.

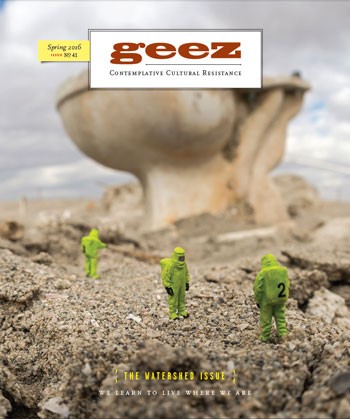

We find inner renewal that fuels outer change. This is a form of working out our personal and collective salvation. I hope this issue of Geez can arouse in readers fresh affinities for the water in and around us, and that this attraction leads to organizing for change.

Aiden Enns is editor of Geez magazine. We welcome your comments and feedback to anything in this magazine. Write to editor@geezmagazine.org, or Editor, Geez magazine, 400 Edmonton Street, Winnipeg,

Manitoba, R3B 2M2.

Sorry, comments are closed.