Context is everything

For those who care about living the Christian faith in a troubled world, the crucial question – the political and deep, life-changing question – is not what we know about Jesus, it’s how we know about Jesus.

For those who care about living the Christian faith in a troubled world, the crucial question – the political and deep, life-changing question – is not what we know about Jesus, it’s how we know about Jesus. The transforming question is not, What do I believe about Jesus? It is, With whom do I gather to understand the life and impact of Jesus?

For example, if I rely on friends who are (or want to be) wealthy for my interpretation about Jesus, I will most likely feel good about a path of upward socio-economic mobility. I will also have a ready answer for those who are poor: they should get a job, work within the system, take out a loan to develop a credit rating.

If I turn to a community of shoppers, television watchers and personal-electronic-device users for my interpretation of Jesus, I will likely find a Christ who died for my sins, offers instant but temporary relief from personal guilt and guarantees long-term rewards of silver and gold in the afterlife.

If I turn to a group of middle-class, educated, white people who are conflicted about their social status (e.g., they can’t decide how to use their power to both “make a difference” and still go to the lake on the weekends) then I will find a Jesus who doesn’t offer easy answers. This Jesus blesses the centurion (the military commander, of all people), heals a paralytic and reclines with the tax collector (whose vocation includes legitimate skimming).

I’m more and more compelled by the notion that we don’t know much on our own. We need to discern with others to make meaning in this world. I say this descriptively, because that’s what I see myself doing all the time. But I also say this in reference to how we form knowledge. We develop a social consensus around our common interpretations, and then bless this agreement with grand notions of “right,” “good,” “true,” even “natural” or “it’s simply a fact.”

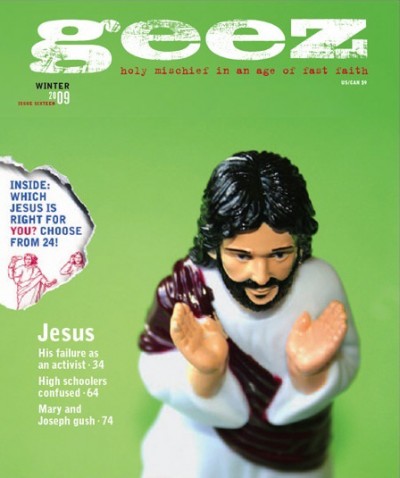

I’m struck by how depictions of Jesus change with social concerns. See, for example, the depiction of a feminine Jesus at a peak in U.S. domesticity in the late 19th century on pages 58-59, and the muscular boxer Jesus of today’s military celebrity culture on page 36.

Our self-identity is profoundly shaped by the communities in which we belong. Theologian Paul Tillich wrote about the the “polar tension” between individuals and community; you can’t have one without the other. Every community is made up of individuals; it needs free thinkers to remain vibrant. Individuals form identity from their community and are alienated otherwise.

As I turn to others with questions, they shape my reality. These influences are not just friends, but also books, blogs, magazines, salons or church groups. I find this approach to my faith hopeful. As I despair over notions of belief, I can find a way forward not by asking a new question, but by gathering with friends (or books, articles, movies) who are dealing with the similar concerns.

As I continue to develop as a person of faith, I apply this communal hermeneutic (way of interpreting) to the story of Jesus. For example, if I want to feel a threatening pull of the gospel, I need to hang out with dispossessed believers. If I want to find energy and concrete options for solidarity with those on the margin, I need only begin engaging with those who are already there. (For a powerful discussion on solidarity and community across lines of class and race, see the various responses to Nate Buchanan’s article on pages 68-71.)

This is a very Anabaptist way of understanding faith formation. They were seen as rebels in the 16th century because they refused to give those in power authority in interpreting the scriptures. They took the books into their own hands and discerned together a word for the day. They were called radicals, insurrectionists and heretics (there’s a big book of martyr’s stories as a result).

This communal approach to interpreting the story of Jesus allows for differences according to contexts. This makes it tremendously difficult to find the way of Jesus. (Hence we depict 24 different Jesuses in a special table of contents, see pages 6-7.)

How do we get past the relativism that plagues the different stripes of Christians? My answer is that we don’t. We have to learn to live together with our differences, this is the reality I’ve come to see in community. I have an SUV-driving brother and a bicycle-advocating sister. This is part of my larger community and also part of me (literally and metaphorically). The question is, whom do I allow to influence me more? To what circles do I migrate to deal with my questions? Jesus, according to my favourite sources, moved among those at the margins.

Aiden Enns is editor of Geez magazine. He can be reached at editor@geezmagazine.org . He lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.