Solidarity’s Long Walk

Step. Move foot forward 45 centimetres. Step. Move foot forward 45 centimetres. Step. Repeat for 30 kilometres and call it a day.

The tiny bones in the feet, the tibia and fibula at the shins, the knee joint, femur, and hip joint ache. Muscles and tendons swell. Hot spots inside the shoes lead to small pockets of fluid under the skin. Spend time protecting these with moleskin and duct tape. Back up onto the feet to step. Move foot forward 45 centimetres.

This was the reality of the Pilgrimage for Indigenous Rights, a 600-kilometre walk from Kitchener, Ontario to Canada’s capital city of Ottawa. In the span of 22 days in April and May this year, 50 people, mostly settler Christians joined by some Indigenous friends and strangers, walked all day on the shoulders of minor highways in Ontario. We ate wonderful meals provided by hosting churches, community groups, and one First Nation cultural centre. We held teach-ins for the community almost every evening and slept on mats on church floors.

Every day we wrote an email to Canada’s prime minister, telling him about the walk of the day, the people we met, and the landscape we walked through. And we reiterated our request: That the federal government keep its promises – to “walk the talk” – to fully adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (also known as UNDRIP). The way it could do this is to support the private members Bill C-262.

This UN declaration is a document completed after 23 years of work by Indigenous peoples from around the world. It contains 46 articles that set out “the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”

Before winning the 2015 election, the current Canadian government had spoken good words of favour toward the adoption of the declaration. However, they are now finding many reasons to stall and leave room for resource extraction and pipelines without Indigenous peoples’ “free, prior and informed consent”.

Two Christian-identified groups collaborated to create the pilgrimage: Mennonite Church Canada and the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Project from Christian Peacemaker Teams. The long and public walk was one answer to the question of how we educate and motivate both church and non-church people to become aware of the declaration. It was also one way to inform those we met that if all Canadians looked at their actions, policies, and beliefs through the lens of the articles in the declaration, we could move much closer to reconciliation with the peoples whose ancestors have lived on this land millenniums before ours even knew it existed.

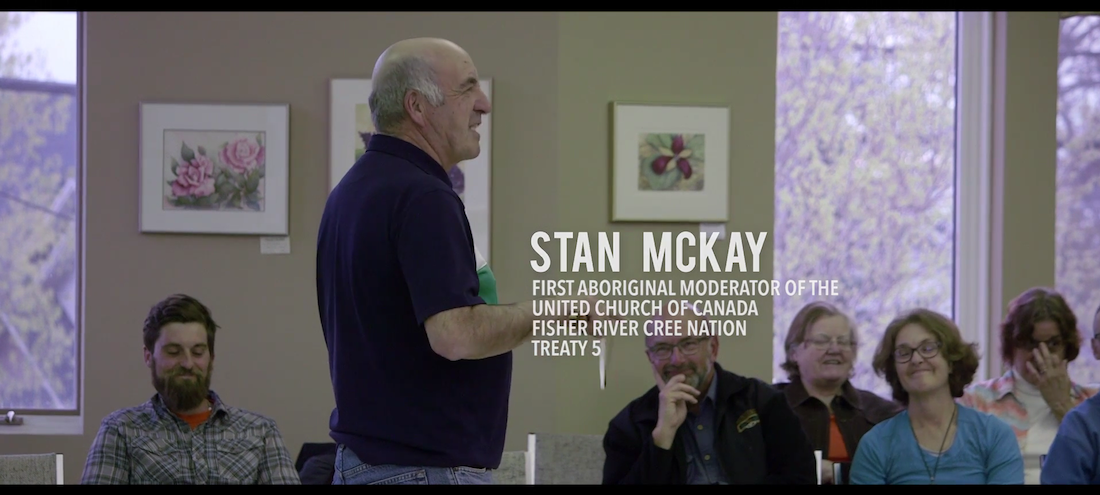

It’s so hopeful to see non-Indigenous people walking in solidarity with Indigenous people, for 600 kilometres, 22 days. . . . It makes me feel hopeful. It makes me feel like change is becoming more and more possible by the day, that people want to do better, and they want to participate in that change. – Leah Gazan, Pilgrimage Discernment Circle member, Lakokta Wood Mountain First Nation (Treaty 4) Credit: This and above image are video stills from Brad Leitch, Pilgrimage for Indigenous Rights, see pfir.ca

With an age range among the walkers of 11 months to 87 years, the journey required patience. The slower pace created time for deep conversation. For six hours a day we moved up and down the line of walkers, encountering new ears and minds to help us reconsider long-held beliefs: things we were taught by our schools, churches, and governments about the Indigenous peoples of this land; colonial habits of thought that we must constantly expose, acknowledge, and change.

Indigenous walkers graciously shared teachings with us to inform our thinking, as did settlers who had been doing this work for decades. Newcomers to the conversation learned the names of the nations who had lived on the land upon which they now live.

The pilgrimage allowed us to really see the land we walked on as we moved from residential suburbs and industrial parks to Ontario farmland to boreal forest and Canadian Shield and back again: taking a minute in the pouring rain to guide the large “grandmother” worms off the asphalt and back to the safety of the earth; learning from a walker studying herbology that the ditch plants were not just weeds, that hawthorn is known to decrease blood pressure and spruce tea can offer healing from sore throats.

The walking also created space for prayer. One of the large flags that we carried through the sunny days pictured two huge bare feet and the words “Praying with our feet.” The monotonous hours gave room to be grumpy, to think quietly, to be grateful. This was a time to honour that of God in each other, quirks and all, and to hear our Indigenous friends tell us that Creator was pleased with our action – that this journey was right and good.

“The walkers are teaching us about the importance of interdependence. They don’t walk for themselves, they walk for others. They walk because they believe that society can be transformed to include even Residential School survivors,” said one evening presenter along the pilgrimage, Stan McKay, member of the Fisher River Cree Nation and the first Aboriginal moderator of the United Church of Canada.

Indigenous friends came from afar to join us in the walking: Pat Makokis from Saddle Lake Cree Nation in Alberta connected with a group she knew nothing about, feeling that she needed to come; David Spenceley came to our teach-in in Peterborogh and then walked for a day to encourage us with his drum and teachings; Romeo Saganash, a member of parliament in the second largest riding in Canada, put on his walking shoes and endured the blisters before teaching why Bill C-262 was important; Leah Gazan, an educator at the University of Winnipeg from Wood Mountain Lakota Nation, took off her high heels and put on bright pink runners to say, “We are all in this together”; Sylvia McAdam, co-founder of Idle No More, drove from Saskatchewan to Ottawa to stand with us on the last day in the Ottawa rally. We heard from all of them that we were “walking the talk.”

At a large teach-in in Perth, Ontario, a local leader, Mirielle La Pointe from Ardoch Algonquin First Nation, expressed gratitude that we had taken up the Indigenous tradition of walking from community to community carrying messages, literally carrying a birch-bark scroll with our message about the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Bill C-262 inscribed into the soft inner bark.

We also heard that we were walking in a line of hundreds of Indigenous people across this land who have marched to bring awareness and resistance to the oppression faced daily by Indigenous men, women, and children:

2013 The Journey of Nishiyuu, a 1,500 kilometere walk from the Cree Community of Whapmagoostui, Quebec, to Ottawa, Ontario, to bring awareness of the vulnerability of the rivers and lakes after government policy (Bill C45) had removed the protection of the water;

2015 Anishinaabe Water Walk (Treaty 3), a walk along the proposed route of the Energy East pipeline in order to draw attention to threats posed by the 1.1 million-barrel-per-day pipeline;

2015 Walk for All Missing and Murdered Indigenous Men, Women and Children, 4,200 kilometres from Norway House, Manitoba to Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

2017 Mother Earth Water Walk, led by Elder Josephine Mandamin; they carried a copper pot full of water and an eagle staff 2,285 kilometres, from Duluth, Minnesota, and ending at Matane, Quebec, where they meet the waters of the St. Lawrence. Mandamin has walked over 20,000 kilometres to bring awareness to the poisoning of the water.

All those who walk experience the physical, emotional, and psychological benefits of moving their bodies kilometre by kilometre. They depend upon strangers for the hospitality of food and encouragement. They carry messages of resistance, prayer, and protest.

The wayfarers on this Pilgrimage for Indigenous Rights have no illusions about the government’s response to their efforts, but we know we touched the minds of hundreds of people along the 600-kilometre trek. We pray that many will take their first steps – literal or symbolic – on a journey toward rights for all people living in this land.

Kathy Moorhead Thiessen is a member of Christian Peacemaker Teams and a coordinator with their Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Project. She was also a co-organizer of the Pilgrimage for Indigenous Rights. She lives in Winnipeg.

Sorry, comments are closed.