Decolonizing Travel: An Interview with Bani Amor

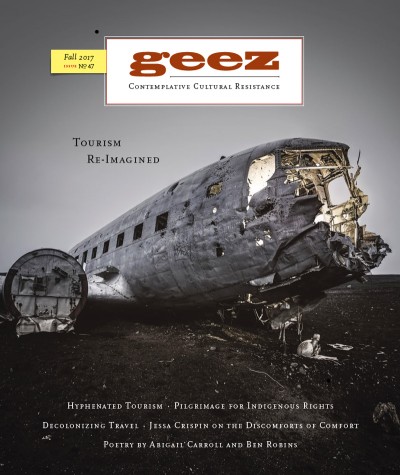

Credit: Jahel Aheram, see link below

Bani Amor is a queer nonbinary travel writer, photographer, and activist from Brooklyn by way of Ecuador, who explores diasporic identities, the decolonization of travel culture, and the intersections of race, place, and power in their work.

They’ve been published in Bitch magazine and Apogee journal, among other outlets. They are a three-time VONA/ Voices Fellow and have an essay in Brooklyn Boihood’s anthology Outside the XY: Queer Black and Brown Masculinity. Follow them on Twitter @bani_amor. Contributing writer James Wilt interviewed Bani Amor for Geez in July.

Geez: When did you first start thinking about this idea of decolonizing travel?

Bani Amor: It was a few years into trying to write professionally: being in the travel writing industry, scoping it out, working within it, trying to see where I could inject my voice, especially for these particular audiences which were mostly white and Western. In the travel writing space, the opportunities are mostly with white editors and their audiences. As a person of colour and all these other identities, it’s like I was already thinking of how to change my voice for this kind of gaze.

I’d already been talking about race, travel, and place in my work, and trying to visibilize more travel writers of colour with a series of interviews on my blog. [This was something] that I had to do to feel like I wasn’t alone and to foster more of a com- munity where we could talk about things a bit more openly. After a few years of talking about diversity a lot, I got really tired and saw what little this meant to the people who were talking up diversity in travel. I saw what their actual intentions were and saw what the actual impacts were, which were not sufficient for what I was thinking of and what I wanted to do with my work.

So really, being in those spaces kind of pushed me to really think about what I wanted to do in my work: what really fascinated me, what challenges me and what I wanted to challenge other folks and this industry with. That’s why I wanted to talk more about decolonization and travel culture, to get really to the root of the issues that I was trying to discuss. And not just change the face of who’s talking about this, but to question how and why there’s a tradition and these narratives that won’t die, and how to subvert them.

Geez: What are those traditions within travel and travel writing that won’t die?

Bani Amor: In travel writing, it’s right there: it’s colonialism. It’s pretty stark. When we look at the history and take a step back to look at travel writing in its tradition … well, first off, I’m not saying travel writing necessarily started with colonization. There are people of colour who travelled and wrote before then, and white people who travelled before then. It wasn’t always a problematic thing. But I do think that travel writing as we know it today was forged in this colonial, European, imperial era of “exploration.”

There’s something zoological about that which hasn’t left. It’s having an anthropological gaze on Others and the entitlement of going to the Other and explaining them to a more “civilized” audience in search of further knowledge about the human race or knowing more about nature. It’s like studying beasts. It might not be that blatant to people these days, but it really does go deep and carries on to the writing of today from blogging, to Condé Nast Traveler, to the way the outdoor industry communicates its message to people and who it does it to. It’s deeply colonial to me.

There’s something zoological about that which hasn’t left. It’s having an anthropological gaze on Others and the entitlement of going to the Other and explaining them to a more “civilized” audience in search of further knowledge about the human race or knowing more about nature. It’s like studying beasts. It might not be that blatant to people these days, but it really does go deep and carries on to the writing of today from blogging, to Condé Nast Traveler, to the way the outdoor industry communicates its message to people and who it does it to. It’s deeply colonial to me.

Geez: What are some of the key factors to decolonizing travel?

Bani Amor: First, it’s thinking about what travel culture is, including travel media. A big part of that is the writing, which has been around since the dawn of this kind of colonization. But also now, in the contemporary world, we have different kinds of media with images and film, and different things that carry all this problematic shit from writing into different kinds of media.

Also, the culture of travel: expat culture, backpacking culture, or the way we talk about being able to travel as if it’s something everyone has to do or should do, or a life-changing growth experience. Those are all cultural codes, the way we in the Western world are able to talk about these things. It’s about asking questions about the origins of those cultural codes.

Yes, you can travel and grow, or whatever. But why do that at the expense of others? Or why can’t you grow at home? Or why do certain people want to travel far, so much, to see a certain people or certain places but don’t really have a relationship to their own home or land, or don’t know much about what happened there or who was originally there, or what it means for them to be where they are now? They’re a little deeper questions.

I think subverting these colonial narratives in travel writing and in media is very much a part of decolonizing that narrative. And the narrative is very important to move on to the next thing, which is real-time impacts of tourism on Native lands, on places where Black and Afro-descendant people live, and what it does to them today.

What happened in order for a mass tourist presence to happen in a certain land? It usually has to do with years of a snowball of factors: local industries being taken over by outside ones, or people made economically vulnerable because of things that usually have to do with imperialism, and how people get to a place where they need money so much that they really do have to sell their culture or make the most out of what’s happening on their land. That’s really not a choice that communities usually make. It’s made for them.

Then there’s displacement. We’ve had people who are historically from a place who don’t have full access of moving around the places where they’re from. And then also having your resources taken from you to serve this temporary presence of all these people who overuse things. There’s an imbalance. Decolonizing, at its root, is about sovereignty for Indigenous people and Black and Afro-descendant people. What I’m trying to talk about with decolonizing travel culture is that tourism and the culture of travel is a really big threat to those people and their lands, to the self-determination over their bodies and lands, and how they want their cultures to survive or be communicated to the world.

Geez: On the subject of local impacts, what can travel mean for environmental consequences?

Bani Amor: There’s always going to be an impact. I usually get a lot of messages about how to travel in way that’s not problematic at all, or how to be a perfect traveller. I don’t think that exists. As much as it may seem, I’m not really here to play a blame game. I’m not the perfect traveller. There are impacts to everything we do: if you get into ethics, you’ll know that no one’s perfect and we’re harming the rest of the world in some way just by living.

The issues around environmental impacts of tourism that I think are more glaring are connected to imperialism or an overuse of resources by people who have more power and what that says about this imbalance, or who deserves more shit, or why it’s okay for a lot of people to just live with the fact that these things are being taken from people. Colonization is still in progress and the environmental impacts of tourism really make that obvious.

Natural resource extraction is one of the bigger problems for Indigenous groups in the world today. When we come to thinking about mass tourism, they’re doing very similar things: it’s not exactly extraction, but overuse of resources damages things. In Bali, there’s a huge water crisis and they depend so much on the tourist economy.

Natural resource extraction is one of the bigger problems for Indigenous groups in the world today. When we come to thinking about mass tourism, they’re doing very similar things: it’s not exactly extraction, but overuse of resources damages things. In Bali, there’s a huge water crisis and they depend so much on the tourist economy.

There’s kind of a sense when it comes to problems that are made possible by mass tourism that you can’t go back: if you’re so dependent on this industry but you’re running out of water, what do you do at that point? It’s very hard to go back and be like, “Well, we can’t have this industry.” They have to work with it and see how they can drink water. But it’s scary, because a lot of people don’t have water to drink, and they’re made more vulnerable to things in the pursuit of drinkable water. The white girls there on yoga retreats are not just going to look at their Jacuzzi, then the thirsty people, have a change of heart and return to Idaho or Portland. So we desperately need to have a conversation before it gets to that point.

Coastal places are the number one tourist destinations. People want to go to beaches, especially for mass tourism: this is where all-inclusive resorts are. People who are historically on beaches are usually fishing; they’re usually fisher folk, folks who have a deep history – tradition or culture that’s bound up with water, the land, marine botany, the animals – and taking care of it. There are people who really know how to take care of the land and it’s bound up with their sense of self, culture, and health.

And there’s a way of thinking that those things can be exploited for temporary gain without looking at long-term impacts, not just for these people who are vulnerable, but for the earth. This shit’s not going to be around forever, especially with what we’re seeing right now.

A lot of development on coastal lands really leads to the destruction of marine botany on those places, which makes those communities much more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and [have] less control over what happens around them. Whenever a disaster strikes, which is very common these days, they have less power over how to handle that and how to ameliorate that. It tends to make it worse for folks who are dealing with a warming planet.

Geez: How do you find that people, particularly white people, tend to respond to these critiques of travel culture?

Bani Amor: It’s very defensive and, “I can do what I want, don’t tell me what to do.” It’s super entitled. I get that from people of colour, I get that from white women, I get that from white men. It happens as soon as you try to be critical of something that people think everyone has a right to. But if you just look at the news or Twitter, we know that you have all these people that are being detained and turned away at airports, there are mass deportations, there’s a “migrant crisis.” And then you have a different type of migrants with so much power, who go wherever they want, impact places how they want, and we don’t want to have a conversation about that.

Bani Amor: It’s very defensive and, “I can do what I want, don’t tell me what to do.” It’s super entitled. I get that from people of colour, I get that from white women, I get that from white men. It happens as soon as you try to be critical of something that people think everyone has a right to. But if you just look at the news or Twitter, we know that you have all these people that are being detained and turned away at airports, there are mass deportations, there’s a “migrant crisis.” And then you have a different type of migrants with so much power, who go wherever they want, impact places how they want, and we don’t want to have a conversation about that.

It’s not totally about the blame game, like “you’re doing this wrong” or “I’m doing this wrong” and “we have to not be wrong so that we can talk about this in a very politically correct way.” It’s not about that shit. It’s about asking ourselves really uncomfortable questions so that we can talk about power in general and the way that it functions in this travel space.

Ultimately, this is decolonizing. I’m not trying to use this term as a metaphor. I want these people, and all of us, to be free and have self-determination. And in order to get to that, we have to talk about this stuff.

That’s the goal. My goal is not so people can travel in a way that makes them feel less guilty. It’s just about challenging ourselves and each other. Any social justice conversation is like that. With travel, it’s a lot more insular: it’s a very insular world, and it’s kind of harder to talk about it in this space because people do feel implicated and like you’re pointing the finger at them.

We’re not used to writing from a place of discomfort. Travel writing is supposed to really glorify ourselves, this sense of self-reflection and growth, both how I was before the trip and how I was after the journey. There has to be a big change that came about from something flowery and emotional. Because of that inherent romanticism that tends to carry on in travel writing, it’s just a little more unpopular to write from an uncomfortable place, or ask questions that we may not have an answer to right now.

I do see a big change. I see a big change in people talking about race: there’s so many travel blogs from people of colour and all these Instagram accounts. There’s more people talking about it. But that narrative that lies at the root of so much of this stuff still has yet to be challenged on more of a communal or mass scale.

It’s not all bad, though! I get a lot of positive messages and things from people kind of like me – diasporic people of colour who are from the West and coming from a generation where they might for the first time have some kind of wealth or privilege – who travel back to our homelands or to other places where we’re put in situations that we might not understand. And then you read something like my work or [an] interview with somebody else, and it’s like, “Oh shit, I felt uncomfortable and didn’t really know what happened or what I thought about it or why I felt weird, and then I read this thing and it makes more sense and now I’m thinking about this stuff as I travel and as I write about it.”

Geez: Are there other people of colour who are exploring similar questions that you’d recommend?

Bani Amor: Absolutely. A lot of my platform and getting on social media and work is about making a conversation that’s been had in the academy for years – because that’s the nature of those institutions, to study a thing from a totally non-romantic standpoint – more accessible to people like me who may have been kept out of those spaces and who also come from a place where they’re working toward social justice. Two shorter, accessible works I’ll name are Inedible Roots: Our Cultures are not Commodities by Esther Choi and Lovely Hula Hands: Corporate Tourism and the Prostitution of Native Hawaiian Culture by Haunani Kay-Trask, which is older but still sadly relevant.

Faith Adiele has been huge in my personal growth as a writer: she wrote this book called Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun. It’s a very involved memoir that’s really cool. She teaches the only travel writing workshop for people of colour in the United States, and probably the West, at the VONA/Voices workshop. I went to the first few years and then was on as staff last year with her. Just being in that space and going to this week-long workshop each year, under her tutelage where she gets into this stuff deeply, she’s pushed me to think how I can – as an activist but also an artist – do better.

Faith Adiele has been huge in my personal growth as a writer: she wrote this book called Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun. It’s a very involved memoir that’s really cool. She teaches the only travel writing workshop for people of colour in the United States, and probably the West, at the VONA/Voices workshop. I went to the first few years and then was on as staff last year with her. Just being in that space and going to this week-long workshop each year, under her tutelage where she gets into this stuff deeply, she’s pushed me to think how I can – as an activist but also an artist – do better.

She’s been huge, and also been talking about this stuff for much longer than I have.

Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place is a book we read in my POC [people of colour] Travel Book Club. That’s one of the biggest books that people think about when they think about tourist occupations as viewed from local people who are not grateful and not going to dress it up in a nice way to make anyone comfortable. She’s very just like, “This is how the fuck I feel about this stuff.”

I do have an interview series with women of colour authors of travel books for a website called On She Goes right now. Migritude by Shailja Patel is also about migrants in Kenya and the history of colonization; it’s a performance piece that she turned into a book. My interview with her and other authors are up on that website.

Finally, Belonging: A Culture of Place by bell hooks is a book I’ve been carrying around with me and referring to for years. It’s been very foundational for me and I highly recommend it for folks thinking about land, race, and community.

Geez: Anything that you wanted to add?

Bani Amor: If anyone’s interested in the things I’ve been talking about, Bitch magazine – which I write for every now and then – will run a series on Fragility this Summer, and I’ll have a long-form feature there on the fragility of the Western traveler. It goes into tourism marketing and how patriarchy works through it, specifically the male gaze and coded messaging of travel media and the effects of it on women of colour labourers, and how tourism marketing is very much sending us a message that women of colour and the land is all for the taking for tourist and male consumption.

Look out for that. My website is baniamor.com. I do a lot of interviews, so if you go on the website there’s so much shit and other people’s work to check out; you’re going to be led to other blogs, books, and resources. And if you like any of it, all of my donation links are up there, too!

James Wilt is a Geez contributing editor and freelance writer living in Calgary, Alberta.

Dear reader, we welcome your response to this article or anything else you read in Geez magazine. Write to the Editor, Geez Magazine, 400 Edmonton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2M2. Alternately, you can connect with us via social media through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Image: Jahel Aheram

Sorry, comments are closed.