Parents Rise Up

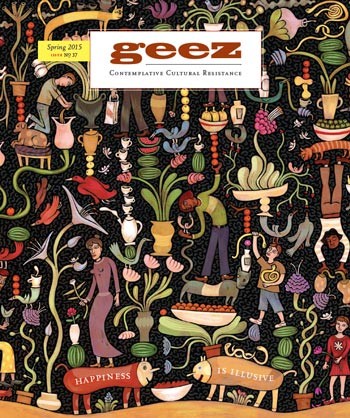

Children at a protest in Broadmeadows, Australia. Credit: John Englart,https://www.flickr.com/photos/takver/5581217769

For the last year-and-a-half, I’ve been the primary caregiver for my 3-year-old son, while my partner completes a two-year master’s program.

We live on campus at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

We spend a lot of time doing leisurely things: walking to the biodiversity museum, baking cookies and muffins, chatting with grandparents on Skype. Of course, I experience inevitable moments of boredom, impatience, and frustration, but right now, I’m wrestling with seeing the time I spend with my child as important work, especially as someone concerned about ecological and social justice.

My partner and I occasionally go to rallies with our son, but we don’t stay long. We go to panel discussions and lectures, but only when we can find a babysitter; often, only one of us goes. We’re locked into a routine that is limiting when it comes to participating in activism.

American journalist and activist Chris Hedges predicts that as struggles against corporatization escalate, two groups, the parents and the fighters, will emerge: “Parents – and I am one – do not make great revolutionaries. We have to go home to put a child to bed. Those who do not have children more easily rise up. Most parents, for this reason, are able to embrace only nonviolent protest.”

While I identify with Hedges’s point that parents are limited by their caregiving, the statement that I can’t “easily rise up” like child-free folks downplays the significance of parenting and its contributions to nonviolent activism.

In her 1989 book, Maternal Thinking, feminist philosopher Sara Ruddick describes how ways of thinking that arise from childcare are inherently nonviolent and can inform ways of peacekeeping. “Out of their failures [and] successes, mothers develop a conception of relationships that undermines the dominant conception of individuality that fuels conquest [and] provocative ‘defence’. They not only modify aggression in the interest of connection but develop connections that limit aggression before it arises.”

Some of the most powerful resistance movements in the last 50 years have been led by parents: the Madres de Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, U.S. mother Cindy Sheehan’s anti-war vigil outside George W. Bush’s ranch, Chief Theresa Spence and the Indigenous women leaders of Idle No More. These parents, the majority of them mothers, gathered in protest because they had lost children and relatives to forces of power. When life is threatened, parents certainly rise up.

I haven’t experienced this threat, in large part because of my privilege. Because I spend my days so comfortably, it takes an intentional effort on my part to engage in resistance movements. But, rather than categorizing myself in an unhelpful and discouraging dichotomy, as Hedges does, why not acknowledge how parenting work can contribute to an activist life?

With my son, I am constantly learning to eschew my position of power over him when he makes demands, to listen first, patiently instruct, and calmly set boundaries when he is aggressive or refuses to listen. I teach him how to communicate in ways that respectfully show what he wants. I’m doing my best to create a peaceful place for my child to grow, be nurtured, and to form friendships with other children and caregivers.

Ruddick argues that I’m learning ways of peacekeeping, and I appreciate her theory. It opens up a space for me on the activist spectrum and reminds me that I have resources and reason enough to “rise up.” Parenting prepares me for an activist life, even if it doesn’t have me on my knees in front of the riot police. I may be there someday, but in the meantime I don’t consider myself on the sidelines.

Katie Doke Sawatzky is the Geez Experiments editor. While she hopes to bring her kids and her cookies to future protests, she’s learning to appreciate the peacekeeping work she does at home.

Sorry, comments are closed.