Move to Detroit

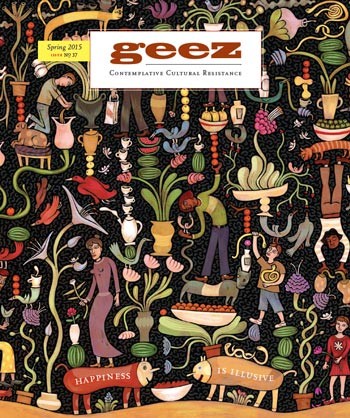

Community art in Detroit. Credit: Russ, see link below.

We will continue to wage love, and struggle against the systems which seek to oppress us. – Tawana Petty, A Poem For Charity (2014)

My spouse, Lindsay, and I were both raised in Orange County, a beautifully manicured playground of lawns and stucco sandwiched between the Southern California mountains and the Pacific. It boasts year-round sunshine and is home to Disneyland, the so-called “Happiest Place On Earth.” No matter where you travel in The OC (the name of the TV show, although no one from the region actually calls it this) you are no more than five minutes from a Starbucks. A few years back, however, this commodified formula for fun became a cul-de-sac for our souls.

While cruising through my teaching career by day and attending seminary classes by night, James Cone’s A Black Theology of Liberation (1970) dropped a bomb on my white Evangelical privilege: “Persons who live in the real world have to encounter the concreteness of suffering without suburbs as places of retreat. To be oppressed is to encounter the overwhelming presence of human evil without any place to escape.” Liberation theology and living in The OC quickly became “Adventures in Cognitive Dissonance.” We knew, deep down, that we would need a change in both location and vocation in order to clear a path towards cognitive congruency.

Eventually, our mentors Ched Myers and Elaine Enns challenged us to embark on a 12,000-mile road trip to visit radical discipleship communities all over North America, and to encounter the concreteness of suffering. After our 75-day journey during the summer of 2013, we felt Something driving us towards Detroit.

On the day after Labour Day last year, a week after we moved to Motown, the Reverend Bill Wylie-Kellermann invited us downtown to join pastors, labour activists, and community organizers to bear witness. It was the first day of Detroit’s highly contentious bankruptcy trial. A few moments after arriving, God showed up on the corner of West Lafayette and Shelby in the form of a fiery middle-aged African-American woman – she had shoved the sanctuary on to the street.

With a team of lawyers, Maureen Taylor emerged from the courthouse just after 9:30 a.m. and beelined for the mic, preaching an urgent message of salvation for desperate low-income residents. She echoed the fifteenth chapter of the Gospel of Luke, animating the victims of the city’s brutal water-shut-offs as “sheep with broken legs.” She proclaimed an abundance mentality: “We have enough gifts for everyone. We don’t have to segregate the population!”

A week later, God showed up again, this time at a church a stone’s throw from Frederick Douglass Boulevard during a panel talk about what it might mean to “occupy the Bible.” On that Tuesday morning, drenched in torrential downpours, Monica Lewis-Patrick hauled the street into the sanctuary. After academics jargoned over “hermeneutical circles” and “the scandal of particularity,” Monica let the whisper become flesh, harkening St. Peter’s proclamation that “love covers a multitude of sins” all over impoverished neighbourhoods in Detroit.

The sins of power and privilege, according to Monica, cling to this city like late summer humidity: backroom deals, shady business contracts, and inhumane water shut-offs. But the power of love rushes in as neighbours come to the rescue via buckets and hoses. Young African-American men like “Rome,” “Kitchen,” and “Razor” deliver gallons of water to those in dire straits all over this 139-square-mile post-industrial apocalypse. There’s no giving up. As Monica proclaims, “It’s not their fault, but it is their fight.”

Maureen and Monica break into sermon wherever they go, a style that African-American scholar Vincent Wimbush refers to as “a more consistent and intense and critical focus on the Bible as script/ manifesto that defines and embraces darkness.” Here in Detroit, this manifesto has instinctively harmonized the seminary, the sanctuary, and the street into a movement largely composed of women of colour. Their lifelong struggle against racism, socio-economic, and political injustice has honed a persevering spiritual vitality – Debra Taylor, Valerie Burris, Tawana Petty, Alice Jennings, Ebony McClellan, and the late Charity Hicks who, before she was killed in a hit-and-run this summer, was arrested for resisting water shut-offs and then exhorted the movement to, above all else, “wage love” against their corporate opposition.

So far this year, the City of Detroit has shut off the water of an estimated 27,000 households whose residents are at least $150 behind on their water bills. Approximately 15,000 homes have had water turned back on after they’ve paid the bills or have been placed on a water payment plan. This is bad news for the remaining 12,000, some of whom I’ve had a chance to meet while canvassing with the nonprofit We The People Of Detroit.

Some have signed leases for suites only to find out – after signing the lease! – that water had already been shut off because the owner hadn’t paid the bill. Others have been astounded by six years’ worth of back sewerage charges that recently appeared on their bills in one lump sum. Many just can’t afford it: the average water bill in the city is twice the national average, while the median income in the city is half the national average and almost 45 percent of residents live below the poverty level.

Maureen and Monica are building a coalition committed to the long-term strategy of knocking on every door of the city, listening to the plight of residents, and enlisting them in the struggle. As they lead teams collecting data, informing residents about the water hotline, and setting up 30-gallon water deliveries for those most in need, there’s still time for hugs and tears. They are deeply in touch with pain and suffering; the five stages of grief, experienced daily, drive them towards justice. Even with the odds stacked against them, they refuse to become numb to the harsh realities of what they call Beloved Detroit.

As Maureen and Monica commit their lives to pursuing a prophetic truth that, according to Cornel West, “allows suffering to speak,” they are sustained by laughter, a spiritual discipline that organically arises from storytelling. This could be a re-telling of the day’s events or yet another recollection of the time Monica’s dad barbecued outside in shorts on a snowy Christmas Eve. The struggle against injustice is sustained through improv: head-shakin’, howlin’, and hollerin’ down the path to a world that, one day, will no longer need food stamps and foster care.

Our deep roots of suburban happiness are characterized by entertainment and consumerism. But our upwardly-mobile sense of humour can seldom be found outside our enclave of privilege. Here in Detroit, we’ve become acquainted with a different kind of fulfillment: one that arises from a community of oppressed people who are on a mission together. It is not free. It takes on the pain of each other and all those survivors in the city, who, according to Maureen and Monica, “stayed and paid and didn’t walk away.”

I am convinced that what allows these women to laugh out loud and graces them with a rare brand of conscientious contentment is a fervent faith in Something in our broken world that sides with the perspective of those on the periphery. It is a robust hope in the core principle of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream: that truth crushed to earth will rise again.

Maureen has been the state chair of Michigan Welfare Rights since 1999; a native Detroiter known for her creative resistance, she exhorts the homeless and the unemployed to stay in vacant homes for survival. Back in the late ’90s, she set up a circus tent in Detroit so that the homeless would have protection from the elements. Then she moved the whole thing to the Capitol lawn in Lansing. She lost her bid for city council in 2001 on a budget of $150. Then she ran a competitive community-based operation in 2005 and was defeated by a devious opposition.

Monica was born in Tennessee, but she was made in Detroit. The youngest daughter of a master sergeant mother and a father who served two tours of Vietnam, she greets everyone with “Sir” and “Ma’am.” She moved to the city in 2008 and joined up with a grassroots community of women resisting the mayor’s unjust emergency management proposal (basically a dictatorship with no oversight over decision-making and spending) for the public schools.

In 2013, while the opposing city council candidates were spending leftover campaign cash on clothing to look “sugar sharp,” Monica was surviving on a shoe-string budget (less than $15,000) and an army of teenagers phone-banking and canvassing in exchange for pizza and ice cream. She lost a tight race that is still clouded with questions over voter fraud.

Back in the summer, when Maureen and Monica sent weekly invitations to the United Nations to come investigate the dehumanizing water shut-offs in their city, they did not really imagine the behemoth would take them seriously. But, indeed, two UN rapporteurs came to Beloved Detroit for 72 hours in mid-October and, just as civil rights leaders petitioned the UN in 1951, Maureen and Monica boldly charged “genocide” on the emergency manager, the governor, and the President of the United States himself.

After touring the sites, hosting a town hall for testimonials, and interviewing a range of folks from victims of shut-offs to Mayor Mike Duggan, UN officials found Detroit to be in violation of international law:

Low-income African-Americans in Detroit are being asked to face impossible choices – to pay their rent or their water bill, to pay their medical expenses or their water bill. These are not choices we expect people to have to make in one of the richest, if not the richest, country in the world.

When the UN came to Detroit, it was “a watershed moment,” according to Maureen. These women now have international leverage. Inspired by their struggle to rehydrate Detroit, people call them from Tokyo to Turkey. But the fight has just begun – up to 150,000 tax foreclosures are coming in 2015.

In this city, water shut-offs are just one of the insidious manifestations of what activist and author bell hooks calls “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” These courageous and compassionate women of colour stubbornly confront power and hubris, with a blend of prayer and humour. They are galvanizing a grassroots resistance that disregards the saying, “We may not see it in our lifetime.” Lindsay and I miss our friends and families in Southern California, but we have found what we were looking for in Beloved Detroit.

After a 12,000-mile road trip visiting alternative Christian communities throughout North America, Tommy Airey and his wife Lindsay discerned a move to Detroit to throw down with the radical disciples at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. In their free time, they seek happiness on runs on the Detroit River, watching Kansas Jayhawk basketball and listening to stories about Rev. Bill Wylie-Kellermann getting arrested.

Image: Russ

1 Comment

Sorry, comments are closed.

I was born in Detroit and I also remember the hazy, lazy good times I experienced in southwest Detroit. I am saddened by the “bad press” the city has received lately, but encouraged by the courage of these women who “won’t be quiet.” This was an insightful presentation that has opened my eyes to circumstances that I was unaware of. Kudos to the writer who set out to get a “deeper cut” of life.

Victoria Watts May 18th, 2015 3:37pm