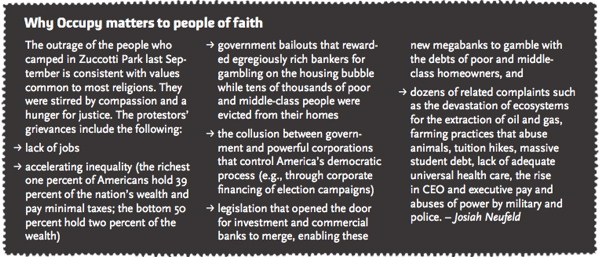

Occupy Wall Street’s altar call

Bishop George Packard (right) was among the first to climb over a fence into Duarte Square next to Trinity Church in New York, and face arrest.

Credit: Adrian Kinloch, http://www.flickr.com/photos/akinloch/6528496247/in/photostream

I just got off the phone with Walter Bergen and I’m uneasy.

Occupy Wall Street is “a straw fire,” Bergen said matter-of-factly. “Lots of heat to begin with and no substance.” He was kind; he didn’t make me feel foolish for my zeal; he agreed that the economic inequalities that sparked the fire are real and unjust. Then he explained why he didn’t think a bunch of starry-eyed activists camping in a park were going to change the world.

Now Bergen’s cool logic is sitting uneasily in my head next to the sharp-edged words of Chris Hedges:

“Occupy Wall Street is the force that will revitalize traditional Christianity in the United States or signal its moral, social and political irrelevance.”

Hedges, political author, former correspondent for the New York Times, and the son of a Presbyterian minister, made this forecast in an impassioned speech in Zuccotti Park on the first Sunday of Advent. The church, he said, has failed to “condemn the crimes and cruelty of the corporate state” and has misused the Gospel to “champion unfettered capitalism, bigotry and imperialism.”

I had phoned Bergen because I wanted to hear what a conscientious, capitalist Christian would say about the movement that drove hundreds of thousands of angry people in 900 cities around the world to occupy public space and swear they wouldn’t budge until something changed.

Bergen is committed to trying to make the world a better place – mostly by leveraging capital. The 55-year-old Mennonite entrepreneur who lives in Abbotsford, B.C., Canada’s equivalent of the Bible belt, supports Mennonite Economic Development Associates, an organization of business people committed to making small loans available to the working poor around the world. Eventually you have to stop being “prophetic” and come up with practical business solutions

to poverty, Bergen said.

Bergen is wary of anyone who calls for more regulation. More rules will only hurt small entrepreneurs while big corporations with teams of lawyers find loopholes. And taxing the uber-rich will just make them move their money elsewhere. Capitalism isn’t perfect, he said, but it’s the least exploitative system we’ve come up with so far.

Bergen is wary of anyone who calls for more regulation. More rules will only hurt small entrepreneurs while big corporations with teams of lawyers find loopholes. And taxing the uber-rich will just make them move their money elsewhere. Capitalism isn’t perfect, he said, but it’s the least exploitative system we’ve come up with so far.

I rotate Bergen’s argument in my head for days, looking for chinks. What could I say that would convince him that the Occupy movement holds a critical imperative for Christians in North America? I can’t win this debate. I need something that will persuade when arguments fail.

I believe in stories. Here are a few.

A bishop, a cop and a drink of cold water

George Packard relates to people in uniform. He’s worn military combat gear and a bishop’s cassock. He’s “rather conservative” but he votes independent. Packard, a retired Episcopal bishop, told me his story over the phone from the small house he shares with his wife in a well-to-do part of New York City.

Packard only began to suspect that something really important was going on in Zuccotti Park the day he decided to drop off some drinking water for the protesters. He bought 12 boxes of water at Costco and drove down to the park to drop them off. He had almost finished unloading the back of his Subaru when a police officer approached him and threatened to impound his car if he didn’t “move on.” Packard’s military ID didn’t impress the officer. So Packard got behind the wheel, prepared to obey orders. “I looked out over the steering wheel and then back in my rearview mirror and I saw two boxes of water to go and I said, ‘this is ridiculous.’” Packard got back out and told the officer he could go ahead and do what he had to; he was going to unload the water.

In the end the officer let him go, but Packard’s ire was raised and his curiosity piqued. A few days later he joined 30,000 people protesting at Foley Square. He tried to strike up a conversation with a couple of police officers; they ignored him.

So Packard was primed when his friend, Chris Hedges, called a few days later to ask if he’d help him lead an Advent service at Zuccotti Park. It was there Hedges delivered his ultimatum for the church in America. His speech was an appeal to the leaders of Trinity Wall Street, a venerable Episcopal church in Lower Manhattan, to turn over Duarte Square to the protesters. Early in the Occupy Wall Street movement protesters had identified the fenced-in gravel lot belonging to Trinity Wall Street as a potential campsite. So after police evicted the tent village from Zuccotti Park, organizers approached Trinity and asked permission to set up camp in Duarte Square. The church’s answer was an unequivocal “no.”

Faith coalition meeting at Occupy Oakland, November, 2011. Credit: Cary Bass, http://www.flickr.com/photos/bastique/6307098563/in/set-72157628039773092

Allowing the encampment on church property would be “wrong, unsafe, unhealthy and potentially injurious,” the rector said in a statement on the church’s blog. Although Trinity had allowed protestors to use its building to hold meetings, recharge cell phones and use the bathroom, this was where they drew the line.

Packard tried to negotiate between occupiers and the church. But discussion, street theatre, media coverage and even hunger strikes failed to change the minds of Trinity’s leaders.

“I have this great worry that this venerable parish will be on the wrong side of history in a few weeks,” Packard wrote in frustration on Trinity’s Facebook wall after a failed negotiation. He knew that when the protestors lost their appetite for talk they would act. And he would be among them.

The night before the storming of Duarte Square, George Packard was afraid. He knew about fear, having tasted it as a platoon leader in Vietnam and in a cancer ward awaiting radiation treatment. “I’m a Silver Star winner. I’ve been in combat. But I’ve never been arrested,” he said. On the evening of December 16, he found himself mentally preparing for an act of civil disobedience that would put him, literally, on the opposite side of the fence from the two loyalties of his life: his church and his country.

In the morning Packard donned his clerical collar and magenta cassock, pocketed an emergency bottle of pills for his high blood pressure, and set out to join hundreds of activists massing around the chain-link fence that surrounds Duarte Square. A portable staircase swayed through the crowd and came to rest against the fence separating the protesters from their objective. Packard was among the first on its steps.

In the morning Packard donned his clerical collar and magenta cassock, pocketed an emergency bottle of pills for his high blood pressure, and set out to join hundreds of activists massing around the chain-link fence that surrounds Duarte Square. A portable staircase swayed through the crowd and came to rest against the fence separating the protesters from their objective. Packard was among the first on its steps.

He was also among the first handcuffed and escorted to waiting police vehicles.

Packard remembers a moment of illumination as he crossed the fence. “When I jumped in, these scales fell off my eyes,” he said. “I thought: this church that I grew up in and loved is reforming itself.” To him it was clear: the centre of Christianity had fled the cathedral pews and was alive “in the streets.”

Why does the church continue to fixate on the small questions while ignoring the big ones? asked Packard in a post on his blog, bishopsnotebook.blogspot.com, at the end of January. “For Martin Luther King, society is not educated by the Samaritan story (charity) but by the larger question of why injustice plagues the entire Jericho Road.” Why is the church comfortable with charity, but fails to move towards solidarity?

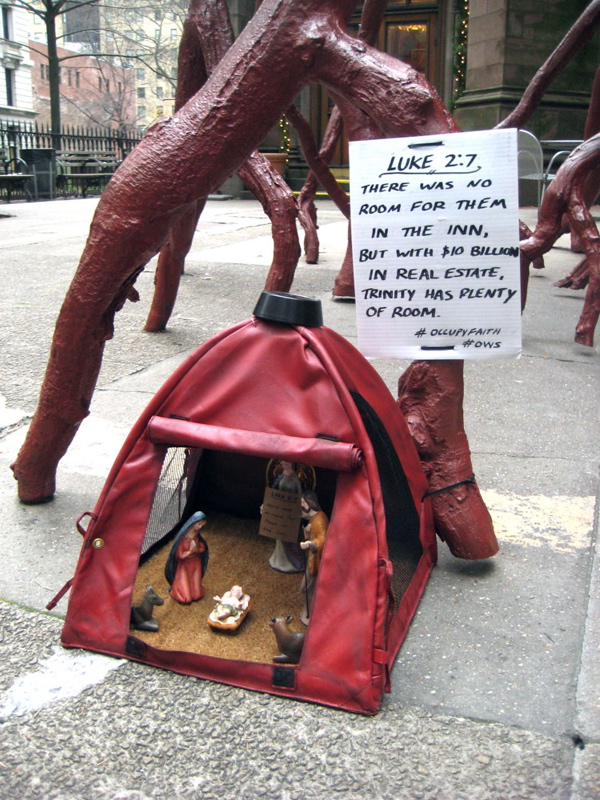

A manger scene for baby Jesus given to Trinity Church pastors, December 2011. For a video of the installation with media cameras and prayers, see yeslab.org/trinity

Credit: Poster Boy, http://www.flickr.com/photos/posterboynyc/6550614955/in/photostream

When Kristin met Sallie

Kristin Rawls grew up in North Carolina, an “earnest liberal-evangelical” who believed God had a plan for her life. She “prayed, studied hard, said no to drugs,” and took out a loan for university. She finished her undergrad degree and started a PhD program at Penn State University. Rawls was earning high marks and living on the $14,000 per year she received from the PhD program. Then she was diagnosed with lupus, a potentially life- threatening autoimmune disease. Because her insurance didn’t sufficiently cover her health needs, she was forced to take out “astronomical amounts of loans” from Sallie Mae (formerly SLM Corporation) and Citibank. Her illness started to interfere with her studies, and the university wouldn’t let her take a semester off with health coverage, so she had to drop out.

At 31, Rawls is a smart, educated, articulate woman who can’t find a stable job. She writes freelance articles day and night to pay the bills. She’s more than $100,000 in debt. Her credit rating is destroyed, and she can’t rent an apartment without a co-signer. She fears she will never be able to own a home or raise children.

Rawls swallowed her shame and published her story in the online magazine Killing the Buddha because “refusing to be silenced by shame is the first step in fighting predatory student lenders.”

Rawls has run out of patience with Christians who don’t get that Occupy is about class warfare. “Occupy Wall Street is not perfect, but it is the first sustained critique of class injustice in this country in my lifetime,” she writes. She gets upset and starts to swear when she hears left-leaning Christians like Jim Wallis and Shane Claiborne offer cautious support for the protestors while backing away from the language of liberation theology and class warfare. She doesn’t want prayer. “I want ‘fellowship’ with people who are outraged with me and who practice solidarity by showing up when it matters and advocating for real economic justice,” she wrote. “I want you to use your clout and influence to help shut down predatory lenders like Sallie Mae and Citibank. When I say, ‘fuck your prayers,’ I say it with teeth.”

Signs of the Community

The Community of Heaven is like a pearl hidden in a field (or a park in Lower Manhattan). A rich person went out and found the pearl. Overcome by great joy, the person sold everything and joined this collective, non-hierarchical movement. Those who have ears, let them hear.

In Vancouver, Beth Malena, a minister in the Downtown Eastside, saw the Community of Heaven at work when Occupy Vancouver gave her homeless friend, a man named Ricky Lavallie, a voice in its decision-making circle. Some of Lavallie’s new friends started teaching him to read and write.

In Vancouver, Beth Malena, a minister in the Downtown Eastside, saw the Community of Heaven at work when Occupy Vancouver gave her homeless friend, a man named Ricky Lavallie, a voice in its decision-making circle. Some of Lavallie’s new friends started teaching him to read and write.

Erica Moulinier found the Community of Heaven camped out on the front steps of Philadelphia’s city hall. Occupiers made room for the homeless, shared their food, identified the needs of the most vulnerable, and devised solutions. When people living with addictions needed to get to Methadone clinics, occupiers arranged transportation.

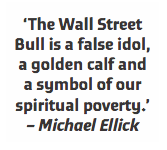

To add what they called a “biblical perspective” at the protest, three demonstrators showed

up at Occupy Chicago with their offering: a golden calf, October 26, 2011.

Credit: John W. Iwanski, http://www.flickr.com/photos/usachicago/6284576824/in/set-72157627801242178/

Michael Ellick, a minister at Judson Memorial Church in Lower Manhattan, radiated the Community of Heaven as he marched with Christian, Muslim and Jewish faith leaders behind a makeshift sculpture of a golden bull. The idol’s bright skin caught flashes of sunlight as it lurched through the streets of New York City on the shoulders of four men in suits. Its papier-maché stance mocked the lunging, 7,100-pound bronze bull on Wall Street, a symbol of financial optimism. “The Wall Street Bull is a false idol, a golden calf and a symbol of our spiritual poverty,” shouted Ellick. Judson Memorial members housed protesters in its basement, wrote liturgies for street marches, hosted public communion services and convened meetings of sympathetic faith leaders.

In San José, California, Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church invested in the Community of Heaven when Father Eddie Samaniego announced to the press that the church and parish school, with a combined annual budget of $3 million, was divesting from the Bank of America. For years the church had listened to the lament of its community. Since 2008, nearly 3,500 homes within the parish had been foreclosed on, and families evicted. The Bank of America held 90 percent of those mortgages. “We tried to meet with them. We tried to advocate for the people they were foreclosing on, and there was absolutely no cooperation,” Samaniego said to Geez in a phone interview. “We finally said, ‘enough is enough.’” Hours after Samaniego announced his church was moving all its money to a credit union called Micro Branch, two representatives from the Bank of America showed up at his door. “Why should I talk to you now?” Samaniego asked. “Adios and good luck.”

In San José, California, Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church invested in the Community of Heaven when Father Eddie Samaniego announced to the press that the church and parish school, with a combined annual budget of $3 million, was divesting from the Bank of America. For years the church had listened to the lament of its community. Since 2008, nearly 3,500 homes within the parish had been foreclosed on, and families evicted. The Bank of America held 90 percent of those mortgages. “We tried to meet with them. We tried to advocate for the people they were foreclosing on, and there was absolutely no cooperation,” Samaniego said to Geez in a phone interview. “We finally said, ‘enough is enough.’” Hours after Samaniego announced his church was moving all its money to a credit union called Micro Branch, two representatives from the Bank of America showed up at his door. “Why should I talk to you now?” Samaniego asked. “Adios and good luck.”

May Day 2012

Walter Bergen may be right about what Occupy hasn’t done: articulate a viable alternative to corporate capitalism. But what Occupy has done is this: defy the empire, stand in solidarity with its victims, model a new way of holding power, enact radical democracy, extend hospitality, demonstrate abundance and remain non-violent in the face of brutality.

Maybe stories aren’t enough to persuade – even stories of conversion or oppression or

eyewitness accounts of the Community of Heaven.

Maybe you had to see it to become a believer.

I wish I could say I saw and believed. I didn’t visit a single encampment while Occupy inhabited public space in my city. But I’ve been collecting stories, and these stories have kept Chris Hedges’s prickly words rolling around in my gut.

As I write, the movement is underground, germinating, getting ready for a mighty awakening on May 1, 2012, say organizers in New York City. Maybe by spring I’ll be ready for the second coming with a little more faith – with the kind of faith Packard saw in a protestor confronting the rector of Trinity Wall Street. When the rector asked him what he wanted, the protestor looked at him “innocently, eyes open, unblinking,” and said: “We’re here to change the world.”

Josiah Neufeld is a contributing writer to Geez magazine. He lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.