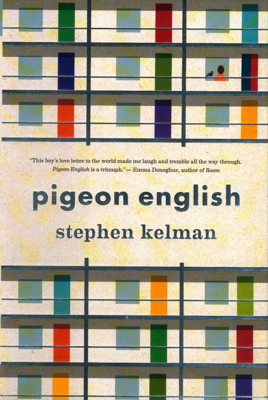

Pigeon English

Pigeon English

by Stephen Kelman (Anansi, 2011).

A book review by Julienne Isaacs

“The window at church is fixed but you can still see where the bad words didn’t come off properly. . . I couldn’t concentrate on praying because I kept remembering them. The prayer sounded right when Pastor Taylor said it but it came out wrong in- side my head. Me: ‘Dear fucking God, please stop all the bad shit happening. Thanks a fucking lot. Amen.’ Asweh, lucky it was only in my head!”

“The window at church is fixed but you can still see where the bad words didn’t come off properly. . . I couldn’t concentrate on praying because I kept remembering them. The prayer sounded right when Pastor Taylor said it but it came out wrong in- side my head. Me: ‘Dear fucking God, please stop all the bad shit happening. Thanks a fucking lot. Amen.’ Asweh, lucky it was only in my head!”

Few writers nail a “voice” as well as Stephen Kelman does in the principal character and narrator of Pigeon English, 11-year-old Harrison Opoku. In fact, it is difficult to think of Harrison as a character at all – days after I finished this novel I heard his chatter rattling in the back of my brain. Pigeon English will no doubt be dubbed an “issues novel,” as its plot centres around gang-related violence in London’s inner city schools. But it is also a portrait of Harrison.

Recent immigrants from Ghana, Harri, his mother and his older sister Lydia live in a crumbling tenement in a crime-and-grime-streaked section of the city, awaiting the rest of the family’s arrival while coping with the various challenges of adapting to an entirely new culture. Harri’s mother, struggling to feed her reduced family, fades into the background of Harri’s narrative – no doubt taken for granted as all mothers are by their children, her personal difficulties only dimly perceived by the reader. Neither does she seem to perceive the bristling dangers engulfing her children as their lives become increasingly tangled with the life of the community. If she doesn’t appreciate the danger, though, neither does Harri.

His tale warbles from observations of the world around him (rarely the ugliness, often the humour) to descriptions of his classmates’ various skills, especially those of his friend Dean (“I didn’t think Dean would be such a good climber because he has orange hair. I just didn’t suspect it”) to script-like recordings of conversation (“Dean: ‘Have you got any leads?’ Me: ‘She’s not a dogcatcher!’”)

Predictably, at least half of the students at Harri’s school seem to be either gang members themselves or keeping their knowledge of gang activity silent. And the secret at the heart of the book has to do with murder: a student in Harri’s class has been found stabbed, and nobody is telling the police what they know. Harri and Dean, remembering “the dead boy” with fondness, set out to solve the case in the way one might expect 11-year-olds to do – randomly collecting samples of hair, capturing fingerprints on Sellotape and sitting in trees spying on passersby.

But what Harri doesn’t see because of his innocence quickly becomes uncomfortably clear to the reader – nothing is safe in his small world, least of all Harri himself, the closer he stumbles to the truth.

Part of Kelman’s skill with Pigeon English is undoubtedly his ability to balance these two perspectives. Harri’s running commentary is sometimes distractingly joyful, and you can’t help but take interest in the beauty he is quick to find in his surroundings – most particularly the pigeon he feeds on the balcony. But at other times it is impossible to ignore the horrors around him as he blithely reports them. Students are cornered in empty hallways and threatened or abused; others barely entering puberty exhibit openly sexual behaviour. In playgrounds, children make games out of hopping over hypodermic needles; at school, they have to hide lunch money in their socks if they want to keep it. And then there is the murder, underpinning everything. A real murder, in fact – this novel is inspired by the true story of Damilola Taylor, a 10-year-old Nigerian boy who, shortly after his family’s move to England, was stabbed to death by his contemporaries.

Kelman doesn’t have to pound out a message about youth violence in Pigeon English. The message writes itself. But he does find loveliness amid the chaos of the inner city, centred in the essential beauty of Harrison’s voice and character. If this book is to be believed – and I think it is – children can grow up uncorrupted in the very heart of corruption. And if some of them are capable of murder, others embody the hope of the inner city.

Sorry, comments are closed.