Black to the Land

Sarah Thompson (left) and Na’Taki Osborne-Jelks at Hampton Beecher Nature Preserve located along North Utoy Creek in southwest Atlanta in 2014. Credit: Courtesy Sarah thompson: blogfromthebelly.com

The following article is adapted from a chapter in the forthcoming anthology, Watershed Discipleship: Inhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice (Cascade Books, 2016) edited by Ched Myers. Sarah Thompson, the executive director of Christian Peacemaker Teams, spoke with Na’Taki Osborne-Jelks, the board chair and part-time director of the West Atlanta Watershed Alliance, also known as WAWA.

Na’Taki Osborne-Jelks was born in Walnut Grove, Mississippi, and later moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The corridor between her home and New Orleans is nicknamed “Cancer Alley,” because of how many people have been affected by chemical leakages from nearby industrial plants. Her mother’s cancer diagnosis was a catalytic moment for Na’Taki’s involvement in environmental justice struggles.

As an undergraduate student at Spelman College and Georgia Tech, she had the opportunity to participate in local efforts to restore the Proctor Creek Watershed, in which Spelman sits.

“The Proctor Creek watershed is one of Atlanta’s most impaired,” Na’Taki told me, describing, among other things, how people from the suburbs illegally dumped into the communities there. Though transient, Spelman students were invited to team up with long-time residents to do community cleanups and organize community watchdogs to hold people accountable for this behavior. Na’Taki’s involvement as a student with local, off-campus work inspired her for a lifetime.

Sarah Thompson: How did the West Atlanta Watershed Alliance [WAWA] start?

Na’Taki Osborne-Jelks: The City of Atlanta made some decisions about its combined sewer system [in the 1990s, in an attempt to improve and expand its wastewater treatment system to accommodate urban growth,] that resulted in open sewage flowing into Utoy Creek. Utoy Creek flows through some people’s backyards in northwest Atlanta. Those people were not consulted. The people from Utoy Creek Watershed got together with those from neighbouring watersheds [Proctor Creek and Sandy Creek]. . . . We formed an alliance of the watersheds in west Atlanta, hence the name.

There are other watersheds throughout the city, but these were all contiguous and all predominantly African-American. We had various incomes, but still faced some similar challenges. We hope that if we can harness our collective power and our collective voice then we can make a difference on the west side of Atlanta. Particularly, we aim to improve northwest and southwest Atlanta, where African-Americans live, and most are inundated with environmental stressors but are often underrepresented at environmental decision-making tables. . . .

Thompson: In community organizing it’s great to have a success to build on to keep momentum. What organizing tactics did you use?

Osborne-Jelks: Organizing in our watershed is mostly grassroots. It’s going door-to-door, town hall meetings, it’s CallingPost phone trees, some social media . . . It’s going to community meetings, where people are, where they are already gathered. It’s working with faith leaders to some extent, and it’s going to the Atlanta University Center and helping students understand that they are student residents of these watersheds and even if they are going to only be here for four years they have an impact on this environment. Our conversations focused on helping people connect to public decisions, to connect to their neighbourhood, [and] to see how they can make a difference. We also invited people to connect to the land through our visitor’s days, giving them safe experiences on the land and water. . . .

Thompson: I feel we are in a moment on our collective journey where most African-Americans must first meet, or re-meet, the land they live on in an empowered way. We’ve had a disempowered relationship with the land, the last time we farmed en masse in the Americas it broke our bodies, and we broke the land.

The foundation of the U.S. economic system was slavery and our bodies were used to extract as much production as possible from the land. No rest for the land or our people! No wonder so many people of African descent want nothing to do with the “back-to-the-land” movements.

Osborne-Jelks: WAWA’s work is to encourage our population to care for the land on which they live. We’ve been able to get some traction on “green infrastructure,” working with people to see how you get the land to work with you, rather than decide to build something that works against it. That’s why we have visitor’s days at the three land areas we steward. A lifelong connection starts with a visit.

Thompson: What does watershed discipleship look like in Northwest and Southwest Atlanta?

Osborne-Jelks: We have some more structured “rituals,” I guess you could call them, and some more free-flowing activities. One aspect of our faithfulness in this place is facilitating relationships, making it possible for people to visit the ecologies in which we live. The work we do in all three of those watersheds makes it possible for people to touch and feel and see and make the connections with water and land here – not far away in the rural woodlands of Georgia but right here in the city. We began by doing weekly creek clean-ups, and water quality monitoring. We take the water supply to be tested by a partner organization that analyzes the data for contaminants. The water quality monitoring efforts are focused on Proctor Creek, as it is our most impaired watershed. That’s where the most attention is needed now.

We are stewards of the water, but with an understanding that when you take a watershed approach, what happens on the land impacts the water. So I would say that another [watershed discipleship] practice is taking care of the land, for example organizing clean-ups at the 26 acres at the Outdoor Activities Center, and the 102 acres at Hampton Beecher Nature Preserve located along North Utoy Creek in southwest Atlanta. We’ve also saved over 400 acres of green space in the city from being developed!

Thompson: I saw my first image of Jesus as a Black man when I came to Spelman. I can hear him saying, “each time you visit this land, and touch this water, do it in remembrance of me.

Osborne-Jelks: Water is life, like faith, it sustains us. At the same time we are concerned with water quality we need to be concerned about the people through whose neighbourhoods this creek flows. If the city of Atlanta would have been successful with their policy plan to change the infrastructure, that creek would have been full of sewage flowing through their land during times of heavy rain.

…

Thompson: Some people think that people who are oppressed don’t have the capacity to take care of the environment around them, because of the other pressures on their life. Your response?

Osborne-Jelks: Everything is connected. I do think people do get it and can get it. People who live in the Proctor Creek Watershed, in some of the most blighted communities, they still care. You would think that they may not have much hope for how their basic needs are going to be met, but thereis something about these natural resources in our communities that compel them to care beyond just what their circumstances are. Proctor Creek has had significance for people in northwest Atlanta. People’s kids used to swim there, people fished, people used to be baptized in this creek. There is a lot of history in that place, people even used to bottle spring water there. To see what used to be an amenity is now a polluted eyesore that detracts from these communities is motivational and begging for transformation. That transformation has to be driven by the people themselves. And that is what WAWA is fighting for, the ability to transform it to what we want it to be.

This article is adapted from the book, Watershed Discipleship: Inhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice . Used by permission of Wipf and Stock publishers. For order information, contact the publishers at wipfandstock.com.

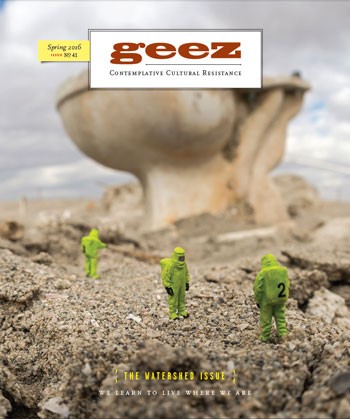

This is an excerpt from the article “Black to the Land” by Sarah Thompson. The rest of the article can be found in the print copy of Spring 2016 issue of Geez, The Watershed Issue.

Sorry, comments are closed.