Christo-anarchism is a move toward non-domination

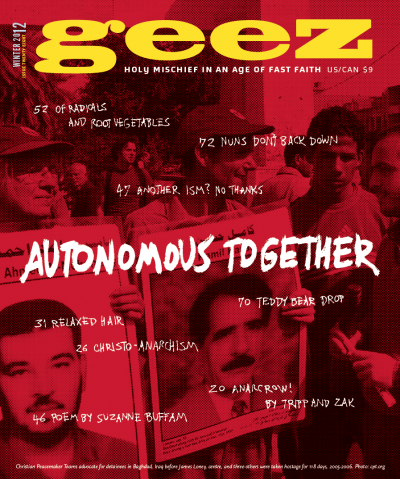

Credit: Donald Lee Pardue, http://www.flickr.com/photos/oldrebel/6131101636/

As a Christo-anarchist, I have trouble finding comrades.

“No gods, no masters” is a slogan embraced by most anarchists. Many anarchists I know assume that Christo-anarchists are either anarchists who refuse to let go of their childhood fantasies or Christians who really don’t understand anarchism. Their assumptions are often correct.

Anarchism, particularly as a loose set of principles, doesn’t often “play well” with Christianity. Most Christians I know assume that I am either amazingly impractical or a heretic. (I am more comfortable with the latter than the former.)

And so, in the interest of making some new friends and allies among you lovely Geez readers, I want to explore some common questions about the anarchist impulse in Christianity.

What does anarchism mean?

Defining anarchism is problematic because it makes assumptions about authority, but I’ll give it a shot. “An-arch” means contrary to authority or without ruler. So anarchism is the name given to a principle or theory of life and practice under which a collectivity or group of people may be conceived without rule. Specifically, anarchism is traditionally understood as both critiquing the State and promoting a stateless society.

That is the basic textbook definition. Most anarchists go further, trying to name those things that oppress or give the State its power; therefore, they seek to reject or undermine other forms of static authority in human relations, recognizing the many forms of oppression (class, race, gender, species, etc.) that make up a system of domination. In recent years, anarchist organizing has increasingly focussed on economic concerns, suggesting that there are things more powerful and oppressive than the State. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (and others) point out that “empire” is supernational, being driven by international banking and supercorporations. It would be fair to say that being anti-capitalism or anti-globalization is as important (or, perhaps, even more important) as being against the State.

What’s a Christo-anarchist?

I am an anarchist because I believe that our world works best when we live with a sense of mutuality – when we care for each other and the land. I’m a Christian because I believe Jesus shows us a way to do that, and I believe this way is rooted in the source of all life. To be a Christo-anarchist is, to me, the logical conclusion of taking Jesus seriously when he calls us to love God and neighbour.

Rather than discussing beliefs in more detail (as you can guess, there’s a wide diversity in the beliefs of Christo-anarchists), I prefer to talk about what a Christo-anarchist life looks like. The emphasis should be on how we live. With that in mind, here’s my working definition of Christo-anarchism:

Christo-anarchism refers to the insight that Jesus’ vision of the (un)Kingdom of God has anti-domination, anarchic implications; it also assumes that only by nurturing practices centred on the presence of the living Christ can we move from domination to non-domination, from death to life, from oppression to liberation and from alienation to love.

Practically speaking, this affects most of our choices in life. Being a Christo-anarchist isn’t a position one has or an ideology one holds, it is practising non-domination, liberation and love. Do you care about homelessness? Rather than voting for a progressive candidate or complaining against the wealthy, offer someone your guest room or couch. Become friends with some folks who are homeless. Being a Christo-anarchist is about putting love into action. As long as love is an abstraction, you probably aren’t loving. The more concrete your love, the more you challenge oppression.

How can you be an anarchist and worship a heavenly King?

Some definitions and expressions of religion assume a controlling, dominant God. Most also assume social structures and hierarchies that anarchists reject. Christian anarchists usually get around this in one of two ways: a) They say the anarchist critique doesn’t apply to God and God-ordained systems. . . that anarchism is only about human-made things. Or b) they suggest that it is possible to hold communally shared spiritual beliefs, practices and stories without affirming social hierarchies and authority (as typically defined). I fall into the second category.

To me, it makes no sense to say, “God is a big King who can obliterate all other kings; therefore, I’m an anarchist.” I would rather say, “The way God sustains and shapes existence and calls us to be in deeper relationship is the opposite of how kings function; therefore, I am an anarchist.”

Jesus is an unking, as my friend Jason Evans calls him. He is the king who subverts kingship. Despite our popular images of God, I don’t believe God is interested in either hierarchy or control. Where the president of the United States insists on a troop surge, Jesus calls people to love their enemies. Where dictators seek to secure their own power and prestige, Jesus calls people to serve one another and lay down their lives for friends.

Jesus is an unking, as my friend Jason Evans calls him. He is the king who subverts kingship. Despite our popular images of God, I don’t believe God is interested in either hierarchy or control. Where the president of the United States insists on a troop surge, Jesus calls people to love their enemies. Where dictators seek to secure their own power and prestige, Jesus calls people to serve one another and lay down their lives for friends.

I worship the one who transcends and excludes kingship, the one who calls me friend. But I don’t think it would be accurate to say that I “obey” him in the way that servants obey masters. That is just a first step – a metaphor. Just as most green anarchists believe they should respect, cherish and affirm nature, I am called to worship and love the source of life. Semantics? Not to me.

Aren’t Christians supposed to “submit to governing authorities” and “render unto Caesar”?

Passages like Romans 13 (where Paul instructs Christians in Rome to submit to the government) and Mark 12 (where Jesus says to “give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s”) are problematic for Christo-anarchists. But upon careful reconsideration, each passage is more anarchist than it would first appear. I’ll take these passages up briefly here; see Jacques Ellul’s Anarchy and Christianity, John Howard Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus or my book That Holy Anarchist for more comprehensive answers to this question.

In Mark 12, Jesus is seemingly backed into a corner by the Pharisees and Herodians, who ask whether it’s right to pay taxes. He points to their coin (no good Jew should have a graven image like a coin in their pocket to begin with), exposing idolatry and saying that such things belong to Caesar already, not God. If you’ve got any Caesar-stuff, it should be rendered accordingly. But what is God’s belongs to God.

Dorothy Day offers this quip: “If we rendered unto God all the things that belong to God, there would be nothing left for Caesar.” That gets to the heart of the passage more than anything else I’ve read.

In my estimation, Romans 13 presents the larger problem. Some Christians (like Ammon Hennacy) get around this by simply rejecting the writings of the apostle Paul. However, I would like to offer two insights that help reveal the intent of the passage.

First, the call to “submit to governing authorities” occurs immediately after Romans 12, where Paul challenges his readers to bless persecutors, live peaceably, never avenge, feed enemies and overcome evil with good. Given that Paul is likely drawing directly from Jesus’ teachings, it may be best to interpret the call to “be subject” as an application of the call to “turn the other cheek,” as another way to subvert the power of the ruling empire. It is not a call to mere obedience or happy citizenship.

Second, John Howard Yoder and others have challenged the common translation of the phrase “the authorities that exist have been established by God.” Yoder argues that “the authorities have been ‘restrained’ by God” is more accurate. Paul could be advising readers to refrain from revolt because God is already restraining the rulers.

Second, John Howard Yoder and others have challenged the common translation of the phrase “the authorities that exist have been established by God.” Yoder argues that “the authorities have been ‘restrained’ by God” is more accurate. Paul could be advising readers to refrain from revolt because God is already restraining the rulers.

From Paul’s perspective, the first-century Christians in Rome should not revolt; they should love their oppressors and leave wrath to God. This isn’t because the Roman government is good, but because followers of Jesus are called to the way of love for all. So Paul argues against violent resistance, but his words leave room for nonviolent struggle.

Aren’t anarchists a bunch of young white males? How does that help the struggle for justice?

It certainly doesn’t help: it’s a stumbling block for many Christo-anarchists. It is challenging to find a place within anarchist circles if you aren’t a white male (as I am). When you combine Christianity and anarchism it gets even harder to nurture a safe place. It’s like joining the whiteness of anarchism with the heteronormativity and latent patriarchalism of Christianity.

Considering that anarchists aim to diminish the structures of domination – to align with feminists, to come along-side people of colour and combat racism – we certainly have a great deal to work on here. I look to anarchist people of colour and anarcha-feminists, like my collaborators Nekeisha Alexis-Baker (see her article on page 54) and Joanna Shenk (see her column on page 14) for direction on these matters.

If it’s so tough being a Christo-anarchist, why bother?

Whether we like it or not, those who embrace Christian anarchism are going to find it difficult to really “fit in” with either the mainstream anarchist crowd or the mainstream Christian crowd.

But what is the alternative? Mainstream Christianity has become complicit in the very injustices Jesus confronted. And conventional anarchism leaves me cold – lacking in beauty and mystery and hope that we can ever become more than we are.

Christo-anarchism is the way of repentance, of rejecting, like Jesus, the three temptations of Satan, saying no to our religious, economic and political dominance and working toward a world where nobody has power over another.

If you choose Christo-anarchism, be prepared for a hard road. Anarchists will reject your spirituality and Christians will reject your politics.

The temptation is to try to force it, to try and show why our views fit “perfectly” within our theological traditions or show anarchists how we’re just like them (except that we pray). But I don’t think we should try too hard to fit in at all. Instead we should embrace our peculiarity and let it become our strength. Let us focus on how we can offer a unique perspective and give flesh to that perspective. Instead of trying to blend in, we should find a way to speak boldly as we forge a path that aims to be faithful to the way of Jesus in provocative ways.

Mark Van Steenwyk is a co-founder of the Mennonite Worker (formerly Missio Dei) in Minneapolis. Mark is a writer, speaker and grassroots educator working with groups to help them live more deeply into the radical implications of the way of Jesus. He is one of the facilitators of JesusRadicals.com and co-host/ producer of the Iconocast podcast. Mark has contributed to several books and is the author of That Holy Anarchist (Missio Dei, 2012) and the forthcoming unKingdom of God . If he were at an anarchist DIY festival and had to make his own T-shirt, it would say “anarchism rules!”

9 Comments

Sorry, comments are closed.

Thank you for this, Mark. I pretty much agree with you. And although I am white, I’m not male and I’m not young!

Anne Australia November 25th, 2012 4:19pm

I agree, too Mark, although I would take it even further and say that God is not a strong force/being who “restrains” powers. I’m currently reading John Caputo’s “The Weakness of God”, and it makes a great case for pulling together anarchy and Christianity. Check it out.

Nathan Canada November 27th, 2012 5:47am

Anne, thank you!

Nathan, I’m a little familiar with Caputo’s work, but haven’t read “The Weakness of God.” Thanks for the suggestion.

Mark Van Steenwyk Minneapolis December 2nd, 2012 6:10am

This is moralistically therapeutic, not biblically-based. When Steenwyk attempts to reconcile his predisposed political position with biblical doctrine, he has to take scripture out of context. Contrasting Romans 12 with Matthew 5:39 is a stretch, and also misunderstands the meaning of “turn the other cheek” (which, in its context, was applying to matters of court and law and had nothing to do with subverting the power of the ruling empire).

Steenwyk seems to miss that Paul was not the only one who said to obey the governing authorities — Peter did, too (1 Peter 2:13-25), where he says, “Fear God, honor the king.” These passages go beyond commanding submission to the governing authorities. It says that all rulers and governors have been given their powers of authority by God and that there is no position that God has not established.

Steenwyk tries to redefine the word “established” to mean “restrained.” Ridiculous. The actual Greek word used in Romans 13 is “tetagmenai” which translates as “that have been instituted” or “that has been ordained.” This is not at all “restrained” as he and Yoder would like to suggest. Government is not against God’s design — it is God’s design. At one point, Steenwyk says, “Paul could be advising readers to restrain from revolt.” Does he not know? Has he ever actually done an exegetical examination of Paul’s letter to the Romans or even read a commentary? He shouldn’t be trying to convince someone of what he doesn’t understand.

Paul was a working man and very much up on matters of the law. In fact, he used the law to his advantage when it came to advancing the cause of Christ. Look at Acts 16:16-40 and Acts 22:22-29. The spread of the gospel was his utmost priority, and he used his status as a Roman citizen to accomplish that goal. So we as Americans should use the protections we receive under the First Amendment to advance the gospel.

Anarchy is actually a conflicting belief system to the point of being a paradox, and Steenwyk often contradicts himself. For example, he tries to say Christo-anarchism is anti-ideological, and yet he has a working ideological statement. The ancient Greeks stated that with no law, there can be no freedom. The State is not oppression. When handled properly, it is protection for its people, and it’s a necessary and God-ordained establishment.

To say that God is not “interested in hierarchy or control” is flat-out wrong. To say that you’re some kind of buddy of Christ’s but not an obedient servant is disrespectful. Friends of God? Yes, we are. Yet subjected to his divine authority and giving him absolute control? Yes, we should. Read Psalm 68, which was a Psalm that Paul referenced to the Ephesians, and see just how king-like the Bible speaks of our God.

There are admirable aspects to Steenwyk’s propositions. For example, don’t complain about the wealthy or the government not helping the homeless — do something yourself. I’m small-government minded, and it’s our responsibility to help the poor, not the government’s. That’s something I’ve taught at my church. We can do that without being anarchists. Selling Christo-anarchism as biblically supported requires manipulating doctrine. Steenwyk should very much heed the warnings given against those who try to twist scripture for their own purposes. (2 Peter 3:15-17)

Gabe December 10th, 2012 6:25am

Guess I’ve struck a nerve, Gabe. I’ve done my homework to the best of my ability and stand by it. God bless you as you seek to live faithfully.

Mark Van Steenwyk Minneapolis December 11th, 2012 1:30am

Just a question Gabe. Where do you draw the line on totalitarian government? It’s said that the church was mute under the Nazi’s. At what point should a Christian reject and oppose tyranny? I’d consider myself a Christian anarchist of sorts and while I don’t entirely agree with Mark, I do consider my political and economic views thoroughly biblically sound first and pragmatic second. It did seem you were a little heated (understandably), so I’d appreciate a little more gracious discourse if you please. The state to me is God ordained in that consequences of sinful behaviour is ordained.

John R London ON December 31st, 2012 8:33am

Helpful. I’ll read this a few times. Really like the unique view of the passages. Comment/question: I worked with at-risk boys at a ranch for many years. They were introduced to Christ through their time with us, and many found a new path. Through therapy, mentoring, job-training, etc. most followed a really positive path even upon their return to their home-community. Still, it took cops with handcuffs and guns and the state’s resources to get a hold of these kids and into our program. So, I’m not sure how they would have ever gotten help unless their was some “power” in place.

Rob Jirucha Victoria, Bc January 26th, 2013 4:02pm

there is a long tradition of christian anarchism. one item i’d point to is william lloyd garrison’s astonishing ‘declaration of sentiments adopted by the peace convention’ (1838). it was quoted in its entirety in tolstoy’s the kingdom of god is within, another classic version of christian anarchism.

crispy United States February 2nd, 2013 10:54pm

Rob: How much did structures of oppression or authority create the situations where the boys became at-risk? If cops are the best way to get kids into your program, can our communities get together to conceive of better ways to reach out to at risk kids that doesn’t involve the police? These aren’t easy questions. But I’m convinced it is more fruitful to ask them and live into new directions rather than simply saying the police are the problem.

Mark Van Steenwyk Minneapolis February 5th, 2013 3:26am