Guest Column: I can’t easily dissociate from oppressors

Lunch at an intentional community. Credit: Earthworm, http://www.flickr.com/photos/earthworm/2343726913/

The first time I remember hearing the word anarchist was when my older brother told me his roommate’s mom was one.

How terrible, I thought. It sounded like it had something to do with the Antichrist, and I didn’t understand how anyone would want to be associated with that.

Twelve years later, I work for Mennonite Church USA and have a seminary degree (from Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary) under my belt. Not so long ago I was sharing with a group of Mennonites about my experiences at the Jesus Radicals conference and why I think conversations about Christianity and anarchism are important for the church.

I could tell one woman was feeling rather agitated as I talked about these Christian pacifist anarchists and counted myself among them. She brought up the Seattle World Trade Organization riots in 1999. She had been there and she vehemently reported, “I’ve seen anarchists and they’re all violent!”

Thanks to a spark of inspiration I replied, “Well, wouldn’t most people throughout history say that about Christians too?”

As a Mennonite Christian I believe that Jesus came to undo the “power over” that exists between people. I believe that the Divine calls us to mutuality with all living things. And I believe that the Anabaptist movement has resonances with anarchism.

Now, for those of you who know Anabaptist history, before you go pointing to Münster (a horrific clusterfuck of tyrannical violence in the name of “Anabaptism”), that’s not the kind of anarchism I’m talking about.

Wikipedia defines anarchism as a philosophy that deems the State harmful and is opposed to hierarchical organization in human relations. Furthermore, it says most anarchists oppose all forms of aggression and support non-violence. So who taught us to think anarchists are angry, violent, chaos-loving people?

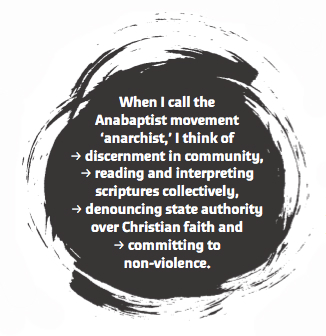

When I call the Anabaptist movement anarchist, I think of discernment in community, reading and interpreting scriptures collectively, denouncing state authority over Christian faith and committing to non-violence. Anabaptism was the “people’s movement” of the Reformation and it was hated by those in positions of power. Slowly, over decades and centuries, as the movement institutionalized, those who carried on the tradition from Europe became known more for their business savvy, respectability and quiet faith.

One example is Henry Clay Frick, who was once known as “America’s most hated man.” He was a steel industry tycoon making his fortune manufacturing coke, a derivative of coal. With his wealth he financed the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company (Monopoly anyone?) and built a mansion that still stands in Pittsburgh. He violently suppressed workers who protested his inhumane business practices, and credited his Mennonite grandfather – whiskey distiller and Mennonite church elder Abraham Overholt – with his strong work ethic, frugality in business and shrewd bargaining practices. A few years ago, before I knew all of this history, I walked around the grounds of the Frick mansion in Pittsburgh. My companions thought this was a “beautiful place to visit.” I felt sick to my stomach. I mean, who had over 20 cars and handfuls of carriages, plus a village of houses and a private bowling alley, in 1914?

As an anarchist, feminist Mennonite who is part of a co-housing community and committed to speaking prophetically into the institutionalized Mennonite church, I’m trying to do my part to restore right relationships.

But I can’t easily dissociate myself from Henry Clay Frick. Not only was he shaped by “Mennonite” values, he was also my great grandma’s grandpa’s fourth cousin. Got that? So, although distantly, I am related to this most hated capitalist.

As a Mennonite I confess anarchism. I also confess I am part of a line of people who have disregarded the teachings of Christ and oppressed others viciously. I confess that the good news of salvation continually calls us to a transformed way of life, toward mutuality with all living beings.

Anarchism calls me to constantly examine my relationships and challenges me to a deeper embodiment of justice and love.

Joanna Shenk is editor of Widening the Circle: Experiments in Christian Discipleship , and a member of the Prairie Wolf Collective in Elkhart, Indiana. If she made an anarchist T-shirt, it would have a spiral and say, “anarchy: the upward spiral.”

Sorry, comments are closed.