A Locavore’s Dilemma

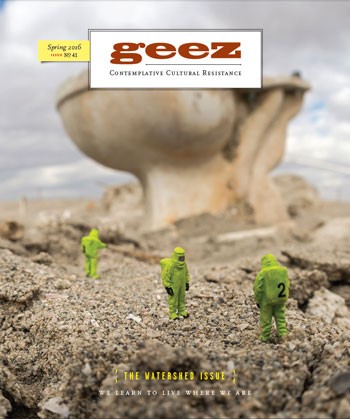

Credit: Federico Moroni, https://flic.kr/p/p9FexS

Few things bring me more joy than the taste of fresh vegetables picked straight from my garden, but last summer my greatest accomplishment was the legumes.

Wendell Berry, in his essay “The Pleasures of Eating,” famously wrote, “eating is an agricultural act.” The industrial food system, however, does a great job hiding that fact (anyone remember purple ketchup?). I once had a conversation with a young boy who had no idea that the chicken on his plate was the same as the chicken pecking in the grass behind his neighbour’s house. He told me, with a serious look in his eyes, “Chicken comes from the grocery store.”

In my second year of university, I began to understand eating as something more than the simple act of refuelling myself. During a course on “Local Participatory Development” I was introduced to Michael Pollan’s book The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Pollan, building off Berry’s idea, writes that eating is “a political act, too. How and what we eat determines to a great extent the use we make of the world – and what will become of it.” Equipped with this knowledge, and a newfound passion for “voting with our forks,” my class embarked on a project to put on a gourmet dinner for 100 people with locally sourced and made-from-scratch food – including farmer sausage, butter, and cottage cheese. The experience was transformative, and I thought I had discovered the cure to all the world’s problems. Clearly, if we were all able to eat locally and organically, we could forever transform the evil forces of globalization and capitalism.

Today, I study food systems in graduate school. When I tell people that I’m studying to become a Master of Science in Food Systems and Society I get a lot of blank looks. I explain it’s the study of how to make the food system more equitable. Food security, according to the United Nations, is achieved “when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization).

In the context of food systems, we know that food insecurity affects close to 800 million people worldwide. That means one in nine people goes hungry on a consistent basis (according to the UN’s World Food Programme). In the United States and Canada, between 13 and 15 percent of the population is food insecure. In the northern territory of Nunavut, one third of all residents are food insecure. In fact, the rate of food insecurity among Indigenous peoples in Canada who live off reserve is more than double that of non-Indigenous peoples. In a world that produces more than enough food to feed everyone, this is a problem worth studying.

I entered grad school under the assumption that the local food movement, with its emphasis on sustainability and community, was the antidote to the destruction and alienation created by the industrial system. Now, the answer in my mind isn’t so dualistic. Scholars, such as Patricia Allen, Rachel Slocum and Julie Guthman, argue that the narrative of the local food movement is dominated by middle-class white people and tends to leave out the experiences and histories of low-income people and people of colour.

While I admired (and still do) the writing of white men such as Michael Pollan and Wendell Berry for the work they have done to bring the issues around food and agriculture into cultural consciousness, I had to admit that it lacks perspective. Local, organic food, as it currently exists, is just not an affordable, or practical, option for many people. What’s more, in an article entitled, “Bringing good food to others,” Guthman argues that the local food movement tends towards a missionary impulse of converting others to a culturally specific (i.e., white) ideal of “getting your hands in the dirt” and eating “good food.”

A few years after my transformative second-year course, I took part in a gardening project. The intent was to nurture relationships between Indigenous and Mennonite peoples through gardening. The project was mostly a flop, in that Indigenous people weren’t interested, but it also embodied Guthman’s proselytizing notion of bringing good food to others. Ironically, it was I, the white woman, who ended up learning an important lesson through this experience. I realized that eating local, growing my own food, and reconnecting to land could be seen as problematic. How could I justify my desire to know and love the land when my living there had caused others to be forced off the land? Was my desire to “go back to the land” just another sign of white privilege, or, dare I say it, white supremacy? Rather than being a solidarity effort, I now see the gardening project as a well-intentioned, but misguided perpetuation of colonialism.

Indigenous scholars and activists have challenged me to think about farming as a colonialist enterprise. In North America, agricultural expansion was often the justification for the removal of Indigenous peoples from traditional lands. In fact, when the agricultural sector was being developed in Canada, a “peasant” farm policy was introduced. It was based on the idea that in order for Indigenous people to make the transition from traditional hunter-gatherer and trader to modern farmer, they must pass through the evolution of farming – from small rudimentary hand tools to modern technology. Yet, many Indigenous communities were already farming, and had been for generations. Not only were these skills not taken into account, in addition, working in vegetable gardens was also a punishment used in residential schools.

For some, then, agriculture is a source of pain. Romantic agrarian imagery is persistent within the local food movement despite the fact that farming (both industrial and local) in North America continues to be dominated by white (male) land ownership and non-white labour. When we valorize the act of getting our hands dirty in the soil, we emphasize our own triumphalist history of settling/cultivating the land and forget the history of slavery and (ongoing) colonization in North America.

I have learned I cannot presume that what I value as a white settler will be universally recognized as good or valuable. Justice is not necessarily an implicit by-product of local or organic movements. I still choose to buy local and organic rather than from Big Agriculture sources, and I treasure my time in the garden (here’s to many more handfuls of peanuts in years to come!), but I have to question my definitions of good food and my desire to claim connection to the land. A good place for me to start might be to step back and ask “what don’t I know?” in order to open up the space for others to define what food-system transformation looks like. In the end, I hope my daily food decisions will reflect a commitment to acknowledging the rightful space and participation of my hosts on this land, as well as those whose voices have been silenced through exploitation or lack of resources.

Zoe Matties recently moved to the Lower Fraser River Watershed on the unceded Coast Salish territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil Waututh peoples. When she’s not busy writing her thesis on food movements, land, and decolonization, she enjoys getting to know her watershed by hiking and bird watching.

2 Comments

Sorry, comments are closed.

thanks Zoe, I really enjoyed your article. great work

Yael Joffe south africa March 11th, 2016 2:28pm

Beautifully said, Zoe!

Sarah California March 12th, 2016 2:35am