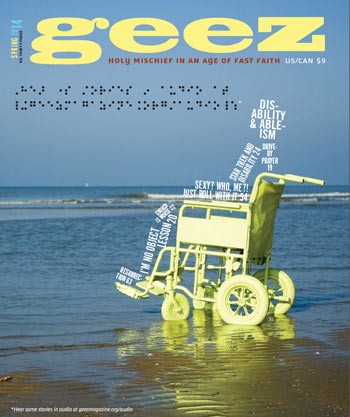

Sexy? Who, me?! Just roll with it

A man and a woman holding hands.

Credit: David Amsler, http://www.flickr.com/photos/amslerpix/8230461579/

At the tender age of 13, I was diagnosed with a neuromuscular disorder and told I might one day end up in a wheelchair.

My young mind could not comprehend the reality of living with a physical disability. I became preoccupied with the fact that I was different from others my age, and I hid my body in an attempt to avoid notice. When I could no longer hide the protruding, crooked and accident-prone signs of muscle weakness, I physically removed myself from groups because of my deep-rooted shame and fear of rejection. Eventually, muscle weakness made walking difficult. I began to rely on a cane, then a walker. I have now used a wheelchair for nearly 10 years.

It was not until I began to use a wheelchair that I truly considered myself a person with a disability. I could no longer pass as able-bodied: the hunk of metal on which I came to rely screamed difference. My disability impacted every facet of my life – none more significantly than my sexuality.

It was not until my mid-20s that I began to explore my sexuality. It has been shocking to discover the vast misperceptions regarding disability and sexuality and the barriers that prevent people with disabilities from exploring their sexuality. People with disabilities are often assumed to be asexual or sexually deviant. When the sexual health of people with disabilities is not ignored or avoided, it is usually discussed only in a very limited medical fashion. Many young people with physical disabilities are not given sexual health education and are rebuffed when they approach medical professionals about birth control and sexual health. This lack of professional, medical-based guidance has led me on a search high and low for sexual health resources.

Published in 2010, Heather Kuttai’s Maternity Rolls: Pregnancy, Childbirth and Disability was one of the first books written by a woman with a disability about society’s perception of sexuality and women with disabilities. Kuttai writes candidly about how her disability affected her identity, and how she experienced a distinct set of social and developmental expectations compared to her non-disabled peers. Many assume that to live with disability is to live without sexuality, a notion that Kuttai internalized at a young age and continues to struggle with despite being married with two children. For her, pregnancy was a short period in which she was able to claim her sexual identity. The visual bump representative of the life growing inside her was an undeniable indicator that she was a fully sexual human being. For me, Kuttai’s words provide a guidepost, a much-needed perspective from a fellow woman with a disability.

Gary Karp is another writer with profound thoughts on disability and sexuality – I have come to cherish my signed copy of Disability and the Art of Kissing. Karp explains that no degree of disability should limit one’s need for intimacy or sexual experience. Disability allows for exploration and experimentation that extends beyond the most basic, physical aspects of sex. Karp believes that disability presents an opportunity to expand our idealistic notions of sexual satisfaction, and he gives a gentle reminder that features of disability (scars, atrophied or missing limbs) provide foundations for forming intimate relationships with others; that these features represent a significant part of our story.

Representations of disability and sexuality have become more visible with award-winning films like Scarlet Road and The Sessions. Both films bring the topic into public consciousness by portraying the experiences of sex workers who take on disabled clients. For some, disability may present a significant barrier to forming a meaningful, intimate relationship with another person, but such a reality should not limit a person’s ability to achieve sexual satisfaction.

Representations of disability and sexuality have become more visible with award-winning films like Scarlet Road and The Sessions. Both films bring the topic into public consciousness by portraying the experiences of sex workers who take on disabled clients. For some, disability may present a significant barrier to forming a meaningful, intimate relationship with another person, but such a reality should not limit a person’s ability to achieve sexual satisfaction.

Though I have lived with a disability for nearly 20 years, I still struggle to consider myself sexy. Showing my body to a new partner is one of the scariest things in the world for me, as it is for many people, for many different reasons. But as long as the sexual lives of people with disabilities continue to be discredited or perceived as subversive, it is one of my many life missions to make disability sexy – not only for my own health, but for the greater good of all who do not fit the narrow and unrealistic social perception of what is considered beautiful.

Jess Turner works as an accessibility advisor at the University of Winnipeg. She explores the intersections of disability and identity through her research and art.

Sorry, comments are closed.