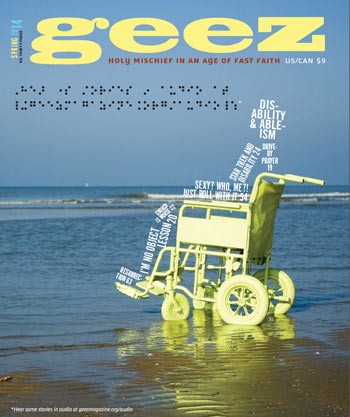

Star Trek and disability

A man dressed as Geordi La Forge, wearing the signature VISOR.

Credit: Nathan Rupert, http://www.flickr.com/photos/19953384@N00/9338491934

This issue of Geez is a special one for me.

I’m coming out as a disabled person (representing for fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue). I’m also coming out as a Trekkie. Believe it or not, the two things are connected, and not just because of all the Deep Space Nine I’ve watched while couchbound in a symptom flare-up.

It was the belief of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry that, if humanity was to survive into the future, we would be required to not only tolerate differences between people and cultures but take special delight in them, celebrating them as one of the best parts of “life’s exciting variety.” It was a high calling then, in the era of the civil rights movement and early space exploration. It feels even loftier now.

A wheelchair, a hearing aid, an inability to work full-time due to chronic illness: these are all examples of facets that differentiate people with disabilities from … the rest. The folks who can function within, shall we say, “normal parameters.”

Star Trek: The Next Generation featured a crew member who was born outside those parameters. Geordi La Forge (played by LeVar Burton) was born blind, so he used a distinctive piece of adaptive tech: the VISOR. It looks like a headband worn horizontally over the eyes, resting on the bridge of the nose like a pair of eyeglasses. The VISOR did not replicate human vision, instead relaying a much broader range of the electromagnetic spectrum, including infrared and radio waves. (Geordi could tell when someone’s heart rate increased, which I always thought was especially cool.) The VISOR figured into many plots over the series’ run, ranking alongside other devices like the transporter and the tricorder as signifiers of the technological advancement the Enterprise crew enjoyed.

If we can accept that, in the future, Geordi’s VISOR is no different than a tricorder, why can’t we accept that so-called “adaptive technology” like wheelchairs or ramps or hearing aids are no different than the technology that the non-disabled rely on every day? Technology like cars and bicycles, and that ubiquitous prosthesis, the smart phone.

A key part of disability theory holds that we need to move from a medical model of disability to a social one. In the medical model, disability is a problem to be solved, an illness to be remedied, a disease to be cured. In the social model, we question the structures that problematize and oppress non-normative people. Why is it that we have to install temporary ramps in private homes to make them visitable by wheelchair users? Why is it that the education system treats all students as though they have the same learning styles and applies the same knowledge assessment to everyone, even though multiple-choice tests are unquestionably unfair to students with dyslexia (or, brains that process text in a different way than what’s considered “normal”). Kids diagnosed with ADD/ADHD struggle to get through a school system that forces them to sit down and be quiet. Never mind that these individuals, once they get into the workforce, find that there are plenty of jobs where having a mind that thrives on a constant shifting of gears is far from a liability.

Then there are those on the autism spectrum, from Asperger’s to non-verbal autistic folks. For some “advocacy” groups, autism is a birth defect to be eradicated. Ask an actually autistic person, and they’re likely to tell you that their neuroatypicality is intrinsic to who they are. We are only now at the very beginning of appreciating how autistic people experience the world in excitingly different ways.

Today, diversity gets a lot of lip service, but we still remain in a place where difference is acceptable only insofar as it still serves capitalism. And in that respect, my Geordi La Forge example breaks down a little. Geordi’s difference had a technological “solution” that still admitted him to the future quasi-military (though the Trekkie in me has to point out that Roddenberry’s vision was for a post-capitalist, moneyless society).

Today, diversity gets a lot of lip service, but we still remain in a place where difference is acceptable only insofar as it still serves capitalism. And in that respect, my Geordi La Forge example breaks down a little. Geordi’s difference had a technological “solution” that still admitted him to the future quasi-military (though the Trekkie in me has to point out that Roddenberry’s vision was for a post-capitalist, moneyless society).

In the present day, many of us disabled folks fight the feeling on a daily basis that we’re not pulling our weight, that we have to justify our membership in community. Be assured that I’m talking to myself when I say that we don’t. The only thing we need as humans to justify our existence on earth is the ability to give and receive love.

There are so many scripts for daily life that we need to rewrite or throw out entirely. In the process of our revisions, I suggest we select a page or two from the Star Trek canon. If we, as a species, are going anywhere, we need to find a way to acknowledge and celebrate difference. And disability is just another difference.

Jenny Henkelman lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where she watches a lot of TV and co-hosts a pop-culture podcast called Fatties on Ice.

Sorry, comments are closed.