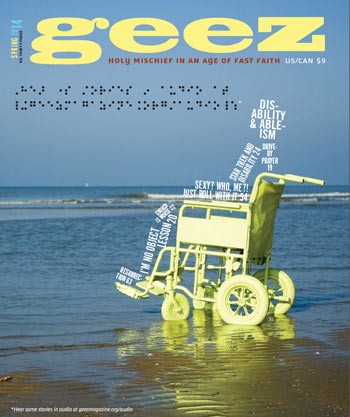

Poverty of access

The Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Credit: Sarah Braun, http://www.flickr.com/photos/89709685@N00/8692757850

In The Soul of Man Under Socialism, Oscar Wilde writes of charity and poverty that “remedies do not cure the disease: they merely prolong it. Indeed their remedies are part of the disease.”

What we are experiencing today is a poverty of access. Just as we have markers for economic poverty (income, assets, etc.), so should we be paying attention to the markers of democratic poverty – the structures of society which do not allow for equal and active participation. Better parking and special bathroom stalls are little more than charity, an afterthought in the built environment. Every building that isn’t wheelchair accessible, every street sign that can’t be seen by the blind and every form of civic participation, like public transit, that is not inclusive, represents our inability to think beyond what is “normal.”

In strictly human terms, there is no such thing as a disability. Disability, rather, is sociological. It denotes the inability to function within the norms of a particular society. We cannot fix a poverty of access with what amounts to charity. Rather, coming back to Wilde, “The proper aim is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty will be impossible.”

Bertolt Brecht thought along the same lines when he wrote:

When there is no longer any violence, there is no need for help Therefore you should not demand help, but abolish violence

Help and violence form a whole

And the whole has to be changed.

We need to stop medicating ourselves with the poisoned thought of disability as a problem of individuals and see it as it truly is: a disease of society given to individuals.

How do we do this? The first step is dialogue. I am reminded of the story of Daryl Davis, a black musician who has a collection of Klan hoods, given to him by former members who left the group after being in conversation with him. When we begin to speak openly, we can start to uncover all the parts of our society that we previously assumed to be “normal.”

The design of the built environment should be at the forefront of this dialogue. It’s hard to be part of the conversation if you can’t get in the door, and where help is needed to navigate a building that “normal” people can access freely without help, the conversation is changed. Architecture deals with the emotional response of a person to physical materials and space. As the architect Le Corbusier noted, architecture is thought to be perceived by an individual standing at 5’ 6”. This awareness is a start, but design must be expanded so as to consider a more universal experience.

Chris Downey is one architect who has begun such a project. After losing his sight in 2008, he began using his new experience of blindness to create enriching environments for the blind as well as the sighted. As he notes on his website, “Great architecture for the blind and visually impaired is just like any other great architecture, only better: it looks and works the same while offering a richer and better involvement of all senses. With this expanded understanding, I offer the potential to enhance the experience in all environments serving a greater proportion of the visually impaired.”

We are missing out on a wealth of experience that could benefit everyone regardless of their relation to society’s norms. We’ve all heard that losing one sense heightens all the others; why don’t we take some of that information and use it to enhance experience through all the senses? We can do better.

As an example of the possibilities, direction, and activation of this change, the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, which is under construction in Winnipeg, Manitoba, is an impressive prototype. As CMHR president and CEO Stuart Murray said, “In our museum, disability will not be treated as a special condition, but as an ordinary part of life that affects us all.”

As an example of the possibilities, direction, and activation of this change, the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, which is under construction in Winnipeg, Manitoba, is an impressive prototype. As CMHR president and CEO Stuart Murray said, “In our museum, disability will not be treated as a special condition, but as an ordinary part of life that affects us all.”

Innovations include tactile markers that provide information about accessibility options for exhibits and galleries, staff training that ensures interpretative programming, software interfaces designed to go beyond the normal functional hierarchy, and accessible walkways so that there is no need to designate a “wheelchair” ramp. All ramps are wheelchair and walking ramps.

Through our architecture we can change the way we move and view ourselves, but only if we change the way we think of ourselves first. As Murray puts it, “The biggest barrier we can remove is the barrier that gets in the way of recognizing each other’s potential, and more significantly than that, the barriers that sometimes cause us to forget that despite our differences, we’re all part of the same human family.”

Nicolas Geddert is a writer, artist and designer born and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He likes drinking scotch and playing board games.

Sorry, comments are closed.