The Washing

The day my cousin Billy started his truck in the garage and rolled up the windows and died was the same day I did laundry and hung it out on the line to dry. Dad told me about Billy when I called him just before midnight to tell him happy birthday.

On that day, I went downstairs to the washer in my friends’ basement, a wicker basket of dirty laundry hoisted on my hip: striped and plain socks, light blue underwear from Target, thrift store shirts, jeans, green bed-sheets, dishrags, three towels, a grey sweater. I hit medium load and cold, cold and dribbled the cup of Cheer liquid soap all around the agitator. Upstairs, I set the kitchen timer for thirty minutes while the clothes washed. I set an egg to boil and graded papers and was startled when the timer went off. I pulled the wet clothes from the washer and dropped them into the basket, nearly losing a sock to the two-inch gap between washer and drier.

I might have used the army-green drier if it were winter but that day the drier sat there drab and artless, out of date, unable to make my clothes smell like the sun. So I took the heavy basket out to the line where clothespins stay year-round, ever ready to clip the shoulders and waistlines of clothes. I clasped one after another, sometimes doubling up the edge of a towel and the toe of a sock under the same clothespin since, over time, pins have been lost and are scarce. My red shirt stuck out its white tag at me like a tongue; the bed-sheet hugged me to itself with its animating gust of wind; the dark blue jeans, unzipped, gaped a lighter blue at the sun.

I left it all to dry and went up to my apartment and, from my window, watched the jean legs kick in the wind and I loved the laundry right then because it spoke of process: the soaking, the lather, the spin, the rinse, the hanging, the sun’s part, and – soon – the gathering in, the dressing, the tucking in of a sheet. And I remembered that once, in summer when I was a kid, I was working in the garden with my older sister. We were bent over, weeding the half-runner bean row and she stood up, nearly stricken, and said, “What if this is all there is? How could you stand it?” I didn’t remember what I had said to her in reply, but as I looked then at my restless jeans and shirts, I asked her question again: what if this is all we’ve got? I didn’t feel the despair with which her young voice trembled; instead I felt that if this is indeed all we really have, it is still so much. I felt as though I was not alone; I was working alongside other bodies and we were making long long shadows as the day wore on.

I think of how acute in me these notions were that day, as Billy started his truck engine, having written a suicide note to my Aunt Becky. He was a postman in his forties.

[…]

Billy, at the end of day, before I could take my laundry down from the line, it started to rain. It rained hard and long into the night and the jeans hung there like black dead weight. I stared at the loaded line and felt futile. Fucking rain, I said, and I actually almost cried, like a spoiled little girl, thinking “What did I even do it for? Now that it’s all ruined?” Not just the work but the loving of the work, the frenzy of foolish hopefulness around it. Maybe that’s when you died that day, when the rain started. You were always kind to me.

I am restless; I don’t want to rest yet.

It rained all night, but in the morning the clothes flapped dry. In the morning I gathered them in as gifts.

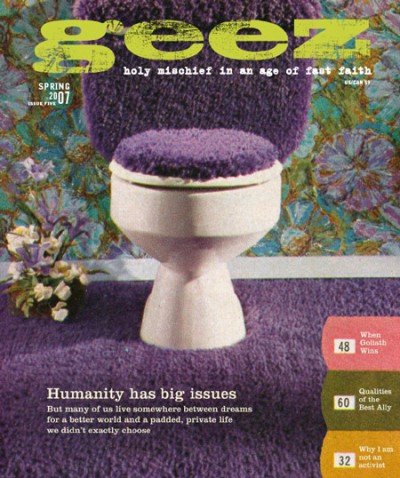

This is an excerpt of a longer article that appears in Geez magazine, Spring 2007.

Sorry, comments are closed.