Guilt – one of many voices

The best decisions I have made in my 67 years were not made to correct guilt but were instead part of the completion of a vision of wholeness for the world and for myself. That does not mean that the strong grasp of guilt has not occasionally lifted its head to guide me when I have ignored more obvious signals or voices.

In the summer of 1963, I chose to interrupt my sojourn as a seminary student and go to Vietnam as a conscientious objector. I went just as President John F. Kennedy increased the number of American military advisors in his effort to turn back communism and stop a partially completed political revolution. That revolution began more than 20 years earlier when the brightest and best of Vietnam were determined to drive out colonialism.

I did not join a missionary group or a service and development group from my church. Instead, I joined International Voluntary Services, a primarily secular organization engaged in grassroots development and education.

This was not a response to guilty feelings about poverty in Vietnam or dis-ease about my country’s special call to pick up where colonial wars left off. I went to Vietnam at age 23 because I wanted to complete something in my life – and I was open to where that completion might lead.

As it turned out that decision couldn’t have been more right. If I had followed the voice of guilt I would have completed seminary and taken up one of the ministries of the church. I would have lived in a perpetual state of inadequate reward from the cycle of confession and imagined forgiveness – a cycle familiar to me from the culture of revivalism in my early years.

More confidence

The more I responded to what I knew within, the voice within, the more confident I became, confident to test all the perceptions of sin, salvation, democracy, violence, nonviolence, revolution, spirit and spirituality. There is always more than one voice within, and guilt is only one of these.

I came to consciousness in a time when the pull of guilt in the revival movement was on the wane. For me, the standard formula of conversion required giving assent to an essentially unbelievable, mechanistic understanding of Jesus’s death and resurrection. Accepting that formula would have covered me with a cloak of guilt which comes from giving dishonest assent to something.

My road to health – as a “recovering revivalist” – went through the villages of Vietnam, through the unfolding war there, and through the villages touched by Jesus on the way to Jerusalem where he was handed the death penalty for sedition, the crime of incitement of discontent or rebellion against a government.

Interconnected

At moments of decision, when voices competed for attention, I somehow came to believe that wholeness – personal, social and metaphysical – are interconnected. I came to work against injustice and for peace because I had seen in the midst of war, starvation, rank injustice and broken spirits hints of reality always present, with the promise of wholeness just beyond the mountaintop.

For a time I thought this wholeness might come from socialism. At another time I thought wholeness might come from a world wide peace movement. Looking back I think I also believed that the one true church would bring wholeness of spirit and society. As those visions merged or gave light to each other, I learned more about the limits of living under the force of guilt.

When we began the work of Christian Peacemaker Teams, I believe there was a wait-and-see attitude. Would this be a rerun of the more strident heavy-handed side of the peace movement? Would it parachute irresponsible people into difficult situations and make things worse? Would CPT organizers forget to root the work in faith? Would it imitate that part of church history that specialized in conflict avoidance? Would it be so churchy that it would do little good in the real world? These questions were out there from all sides of the church.

Peacemaking presence

We realized our primary task was to carry forward a kind of peacemaking presence that pointed to truth and opened spaces for the surprises of peacemaking. We also realized that we needed to build teams. We needed to work together and learn to witness as small groups to the possibility of a world without arms. We had to learn to sing together, celebrate together, pray together and cheer each other on.

Over time, others began to read the Bible teachings on peace with fresh eyes. But this wider acceptance was not matched by an avalanche of persons wishing to join CPT as full- or part-time workers. Most of all I was disappointed with the dearth of workers coming from all the colleges with peace studies programs.

As the work of CPT unfolded, my general view of the wholeness of the world grew deeper. The motivation for our work comes out of a loving embrace of parts of creation where violence is intense. The struggle to break through the apparently heavy armor of violence requires listening, perseverance, critical reflection and an ability to think symbolically.

Sacred sphere

When we enter the world of violence we are entering the sphere of the sacred. We are entering the world where the struggle is not only smart bombs, roadside explosive devices and intelligence on the enemy. We are entering the world where everyone is asking what is worth living for and what is worth dying for – country, democracy, truth, God? In war and violence we are in the world of competing spirits of all kinds – truth, lies, half-truth, gossip, sacred killing and many more.

The problem with any of us relying too heavily upon guilt is that guilt is inherently heavy-handed and comes with a prefigured model for how things “ought” to be done and how we “must” do them. If you listen carefully to the US Secretary of State you will not hear the language of invitation or dialogue. You will usually hear the language of “shoulds,” “oughts” and “musts.”

This is guilt talk done in a top-down style which is how guilt feels when it is applied to someone. It feels heavy, loud, legalistic and self-righteous. This kind of talk doesn’t get us to nonviolent social change.

I wish I could say that the peace movement in general and the faith-based peace movement in particular is free from guilting people into social change. It is not. And when it shows up with its heavy-handed judgmental attitudes you can feel the energy melt through the walls. My observation is that every culture has its own peculiar version of this disease but it takes a while to learn to recognize it.

The rejection of guilt-based social change can be interpreted as weakness. Guilt-based social change workers tend not to stay around very long unless they are made the center of attention which is not healthy for them or for the work.

Best defense

The best defense to ego-based guilt mongering is the development and maintenance of free voluntary groups of people who can choose to act independently and collectively. Healthy folks will usually notice that guilt-induced work leads very quickly to a new set of rules and operating procedures that give little space for the spirit, especially the spirit of transformative love.

For those who care about the world but carry a heavy burden of guilt, my counsel is to take a year of vacation from your guilt and just listen, listen to the other voices within you. Listen to all the voices for beauty, fairness, and wholeness outside of you. This will be a difficult year, but it is worth the risk in a world grasping for wholeness.

Ressurection

Somewhere along this journey the resurrection becomes part of the story, and it is not simply a proposition in which I ought to believe. Resurrection is the way things are when you encounter the sacred and begin to experience the power of transformation that is available. I now believe that people have encountered resurrection power in many ways. For many peacemakers the resurrection no longer becomes a problem for rational assent. Instead the resurrection is inherent in the journey to full life when the Glory of God will be completely visible.

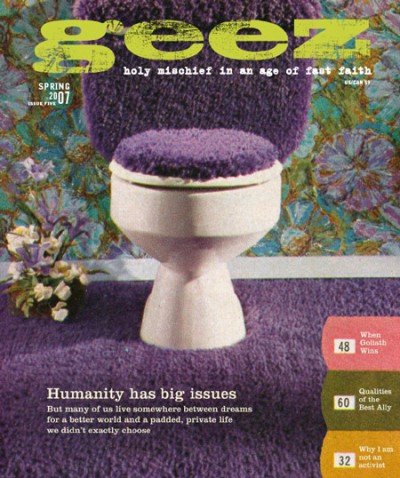

Gene Stoltzfus was director of Christian Peacemaker Teams for 16 years, from its inception in 1988 until 2004. He now lives in Fort Frances, Ontario, and blogs at gstoltzfus.blogspot.com. More from Gene Stoltzus can be found in Geez magazine, number 5, Spring 2007.

Sorry, comments are closed.