The Fasts We Choose

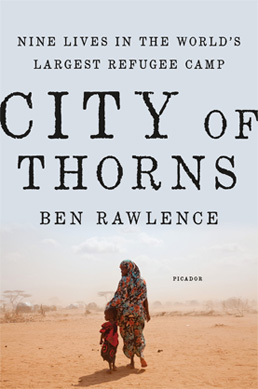

The following is an experimental review of Ben Rawlence’s non-fiction book, City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp.

The following is an experimental review of Ben Rawlence’s non-fiction book, City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp.

For Lent this year, I gave up social media. Well, that’s not quite true. I deleted Twitter and Facebook off of my phone. I am a working writer, after all, and communication and self-promotion are necessities for those who aren’t famous or independently wealthy. But, thanks to Lent, I no longer had the ease and luxury of mindlessly scrolling through the updates and thoughts and carefully curated experiences of those near and far.

In idle moments, my hands rested in my lap, my eyes fixed on a faraway point, my mind drifting, my phone blank and cold next to me. I disconnected, at least a little bit, and it felt good. My anxiety in general went down, I tried hard not to think about the terrifying politics of my country, I stood in front of my bookshelf and picked out a beloved book to reread. What a win/win situation. I got to live a little more in the present, got to kiss my children without fear of them clutching my phone in their grubby hands, and I also got to feel self-righteous and holy about it all. Lent, that season of deliberate lack and fasting, can be about a lot of things. And I had found a way to use it to my advantage.

At the gym, I am listening to a podcast. The commercials are all for boxes of food that come delivered to your door, you just have to cook it yourself. This is a thing now. Perhaps after the novelty of pre-measured ingredients in climate-controlled packages wears off, this becomes something normal you can do. You can pay $30 to have your uncooked meal sent to you. I am at the gym, running in place, surrounded by others trying to escape the incessant Northwest rain, trying to will our bodies and minds into a better place. The sign at the gym in front of me says “warning: staring at your gym crush might cause elevated heart rates.” It is trying too hard to be cheeky, I think to myself. I don’t ever want to get too comfortable in this world; I don’t ever want to ease into luxury and excess because it is too hard to give it up.

I frown when the commercials for the meal boxes come on, and I pick the oldest, frumpiest woman in the gym and stare at her. I look and look and look at her, and then at all of the other outsiders at the gym. The out-of-shape, the elderly, those who don’t know how to use the equipment. I pray blessings on them as I run in place, trying hard to will the love of God onto them. Sometimes, being contrary to the world is the only way I know how to be, the only way I can start to be attuned to the great, vast wells of inequality that surround us.

In the largest refugee camp in the world, Facebook is a gift from Allah. Facebook is the way to escape your life for a few minutes a day.

In the largest refugee camp in the world, Facebook is a gift from Allah. Facebook is the way to escape your life for a few minutes a day.And what is your life like? It is like living in the largest open-air prison in the world. It is like not being allowed to work, not being allowed to move, not being given citizens rights; it is being contained and forgotten; it is your food rations being cut every few years; it is slowly starving while the world looks on; it is sickness and overcrowding and threats of violence and rape; it is a constant hustle; it is the suffocating dream that one day it could all change for you but probably won’t.

The teenagers in the camp – mostly from East Africa, from Somalia and Ethiopia, Oromia and Sudan – they log into Facebook and see pictures of those who won the lottery, those that beat the odds: in Australia, Canada, the U.S., Sweden, Norway. The one percent who made it. The teenagers in the dusty, hot, thorn-encrusted camp see the pictures and ache inside. They create a new word for the feeling of their age: Buufis. The peculiar home-sickness of the permanent refugee, the longing for a different life which ruins your already difficult present. Some sell their meagre rations of food, stomachs constantly hungry, to pay for the chance to get on Facebook and see into this other world. Some create entirely new lives for themselves: they say they live in Minneapolis or London, they “check in” to Disneyland, they badly photoshop their faces onto the team of Manchester United. They fast in order to connect to what is not real to them. They connect in order to survive. They are living in one long season of Lent.

I recently read a book about the lives of refugees in Dadaab, the largest refugee camp in the world, a large and crowded city that no one wants to admit is permanent, a city no one wants to take responsibility for. The men who live there starve themselves so their babies won’t die, mothers choose the sickness and squalor of the camp so their children can get an education, teenagers study hard even though they are not allowed to work and the prospects of both higher education or resettlement are slim-to-none. The stories of suffering pile up, suffocating me. There are no easy solutions, only the glaring truth that I, in so many ways, let this happen. I live in my world, and they live in theirs, and when I die and meet God face to face I might very well be asked why I was not more bothered by this.

One story has stuck tight to me and will not let me go. A man from Ethiopia was separated from his wife and child for six years and finally reunited with them in the refugee camp. He started his own stall in the market, where he would take photos of people and have them processed in Nairobi. Every day he took his precious water rations and watered a square meter in front of his shop. It was the only green grass in the entire camp. He wanted his son to know what it felt like to sit on God’s green earth.

He wanted to bless the eyes of everyone around, accustomed to the reds and browns of dust and clay. It was such a simple act of rebellion, it made my heart well up and break within me. His throat, parched and dry, his feet standing on brilliant green grass. Just one more way to say, your kingdom come, when it all seems so very far away.

What would the people of Dadaab think of the fast I have chosen? I don’t know. All I know is that there are too many stories to hear, too many stories to tell. Of rights denied, of injustice, of people turning to brutality or substance abuse, minds and spirits languishing for lack of hope. Rations being cut every year, whole city-states slowly starving on our watch, and it is all being documented. Where is the word for us, the people outside the camps, the free ones who read and absorb the tragedies and do nothing?

When we allow the suffering of others to cast a pallor over our own lives, we are told to get over it. Find an easy solution, and propagate that. Click over to another website, read something a little easier on the soul. But please: you cannot live in the place of anger and despair forever. You cannot save everyone. The realities are complicated. The solutions always beyond our understanding. Don’t cry in the coffee shop when you read about the refugee camps, the ones that some of your friends grew up in. Wipe your eyes. Drink your coffee, which cost more than what a refugee in Dadaab lives on for an entire day.

“The poor you will always have with you,” Jesus said, and now we just imprison them, though most are guilty of no crime except that of being poor and escaping from violence. They have been there for so long, they will always be there. You shut the book, turn off your computer. Just take a break from it all, you tell yourself. You must, and can, and will, forget.

D.L. Mayfield lives and works with refugees in the United States. Her book, Assimilate or Go Home: Notes from a Failed Missionary on Rediscovering Faith is out from HarperOne in August.

Sorry, comments are closed.