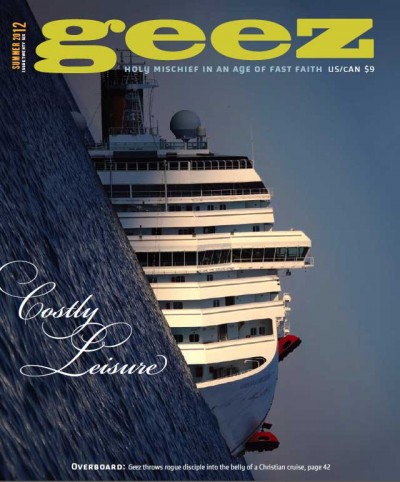

Island Wrecker

Credit: Jeff, http://www.flickr.com/photos/mountainpiratephoto/3998561291/in/set-72157622432823007

In February I realized I needed to get out of Minnesota.

It had been too cold for too many days in a row. So I got on the internet, found cheap tickets to Cancun and booked them. Almost immediately I regretted what I’d done: Spring break in Cancun? I felt I had consigned my family to something like a vacation at Hooters. I imagined drunk college students spilling blue daiquiris on my kids. It would be like Mall of America with a beach. So I called up my brother who had just been to Mexico – he’s the backpacker, tread-lightly type – and asked, “What should I do?”

My brother told me to go to Isla Mujeres, a little island off the coast of Cancun. “It’s Mexico. Really. No discos. No scene. No Starbucks. There’s a great little village. The island’s super small. You can walk everywhere. There’s a market. Cats. Chickens. Iguanas. You’ll love it. But, Debbie” – he said this passionately – “You can’t rent a golf cart. Don’t rent a golf cart. They are environmentally disastrous. They are horribly loud and ugly and stinky. There’s a whole golf-cart-renting industry and it’s wrecking the island. Why don’t people ride bikes?”

Then he described this scenario where he and his girlfriend were riding their bikes on the most deserted part of the island and they’d just stopped to buy a coconut from some guy with a little tin-roofed shack by the side of the road. The guy was opening up the coconut with his machete and his kids were running around chasing their chickens off the road. My brother and his girlfriend were laughing and speaking Spanish to the kids and it was beautiful. All they heard were the wind and the voices and the waves until bam! Suddenly there was this explosion of engine noise and exhaust and 40 golf carts came up over the hill, a battalion of white people with sunburns and beer cans and T-shirts advertising sports teams, yelling “Hola!” over the roar of engines, laughing like it’s funny to say a Spanish word. Tourists. Polluting everything. Putrid, bloated U.S. imperialism ruining the island, destroying any possibility of authentic culture. My brother said, “Go there, Debbie. But promise me: don’t rent a golf cart.”

So, we went to the island and it was beautiful. We walked. I rented a bike to check out how it is to ride all the way around the island. It was great. I wanted my family to see the whole island, but I imagined my eight-year-old Olivia biking up the hills in 90-degree weather against the wind, or going down the hills with cliffs on one side. I pictured her falling over a cliff and crashing on the rocks, or her head being crushed by one of the mopeds that constantly sped and wove through traffic, or at the very least being super unhappy and tired and hot.

So, we went to the island and it was beautiful. We walked. I rented a bike to check out how it is to ride all the way around the island. It was great. I wanted my family to see the whole island, but I imagined my eight-year-old Olivia biking up the hills in 90-degree weather against the wind, or going down the hills with cliffs on one side. I pictured her falling over a cliff and crashing on the rocks, or her head being crushed by one of the mopeds that constantly sped and wove through traffic, or at the very least being super unhappy and tired and hot.

I decided to rent a golf cart.

The kids had no angst about this decision whatsoever. In fact, they were gleeful. And even though I’d developed a deep-seated disdain for the golf-carting-island-wreckers, I found there’s actually something fun about driving a golf cart. I liked feeling the wind and smelling the smells – fish and rotting trash and tortillas. I felt alive and good. I loved my family. I loved the island. I was loving this vacation!

Around 11:30 we stopped at the sea turtle sanctuary I had read about it in my Lonely Planet guide. It sounded like it was going to be cool – real creation-loving, turtle-saving goodness. When we arrived there were 35 golf carts parked outside of what looked like a small zoo. Droves of white people were hooting and releasing environment-wrecking toxins out of their pores, breathing out culture-crushing imperialist white breath. I began to feel a sort of loathing for humanity.

As we walked around, bumping into people and trying to see the turtles, I found I particularly disliked the family that appeared to be from Minnesota. The woman was wearing a Vikings T-shirt. The man wasn’t wearing a shirt. He was carrying a beer. The boy’s ice cream sandwich dripped into the turtle pools. I watched them with the opposite of fondness. The man didn’t want to pay 30 pesos to the Mayan woman sitting in front of the restrooms. He thought it was ridiculous to pay to use the bathroom. The man yelled at the boy and the seagulls. The boy dropped his sandwich on the ground and they got back in their golf cart. I found myself despising, deeply, the golf-cart-riding tourists from Minnesota.

We got back in our golf cart and I made, I have to say, some pretty good jokes about the people at the turtle sanctuary. My husband Jim actually had a lot of funny and disparaging things to say, too. Our moods got a little better. We turned in our golf cart early and went to dinner at the local mercado, satisfied to be salvaging at least some of the day from vacuous tourism.

As we ate, I looked at my family. Jim was drinking a beer. A little salsa clung to the corner of his mouth. My son had a Twins baseball cap on. He did not cover his mouth when he coughed. We were white people with sunburns. It hit me: was I different from the other tourists because I rented the golf cart ironically? Had my kids never dripped ice cream anywhere? Had I never yelled at my kids? I hadn’t really wanted to pay to use the bathroom either. What made us the lovers of the island and the turtles and them the bad white North American imperialists who want a zoo? My self-righteous machinations were so ridiculously glaring.

René Girard makes a pretty convincing argument that human culture is founded on a scapegoating mechanism – we keep our peace and happiness by finding the guilt and ugliness in the Other. We create unity and community by excluding what is “bad” out there. Most of us have learned to form our identities in ways that are in opposition to other people rather than for them. We don’t know how to have an “us” unless there is a “them.” It’s how we do politics, religion, comedy. It works (at some level). But it isn’t harmless. Girard would say this mechanism is the foundation of violence.

My intent in going on vacation was not to drive this home to myself, but I suppose it’s more valuable than bringing home a souvenir. And it helped me write my Good Friday sermon.

Although religion is often used to draw lines between the good and the bad, the story of Jesus goes in the opposite direction. Jesus doesn’t end up rallying the innocent against the guilty: he doesn’t make the bloated Roman imperialists, the self righteous moralists or his friends who betray him the scapegoats. He becomes the scapegoat, takes on all the loathing the world has to give – not to judge us, condemn us or show us how terrible we are, but so we might be free, so we might know love and forgiveness. There is something about what Jesus does that frees us to love life, all of it: messy and belligerent, lefties and republicans, bloated imperialists, self-righteous loathers, Mayans, Americans, chickens and pigs.

Although religion is often used to draw lines between the good and the bad, the story of Jesus goes in the opposite direction. Jesus doesn’t end up rallying the innocent against the guilty: he doesn’t make the bloated Roman imperialists, the self righteous moralists or his friends who betray him the scapegoats. He becomes the scapegoat, takes on all the loathing the world has to give – not to judge us, condemn us or show us how terrible we are, but so we might be free, so we might know love and forgiveness. There is something about what Jesus does that frees us to love life, all of it: messy and belligerent, lefties and republicans, bloated imperialists, self-righteous loathers, Mayans, Americans, chickens and pigs.

We live on a planet that is faltering from the weight of us. Our mere existence negatively impacts the environment. It’s mathematically impossible to be “good” enough to justify our lives. It’s easy to despise humanity in ourselves and in the reflections of our selves in others. The surprising thing is that God loves it. Humans have done what appears to be irreparable damage. But, somehow, I don’t think God sees all the messes we’ve made and throws up God’s hands. I think maybe God looks around and says, “I can still do something with this.”

My loathing won’t solve anything, but maybe love will.

Debbie Blue, a minister at the House of Mercy in St. Paul, Minnesota, is the author of Sensual Orthodoxy, From Stone to Living Word and the forthcoming Consider the Birds. She lives on a farm outside the Twin Cities with three other families and lots of children, chickens, cranes, crows, eagles and sparrows.

Sorry, comments are closed.