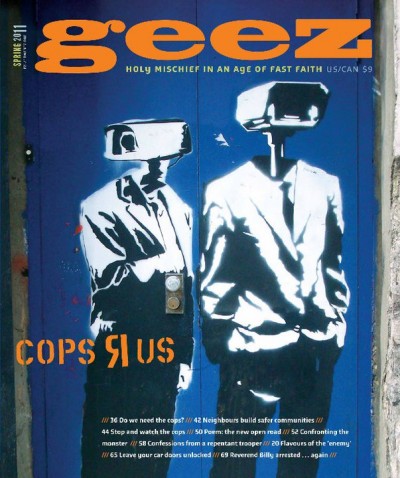

Do we need the cops?

G8 Demonstration, Toronto, June 2010 Credit: Nile Livesey

http://www.flickr.com/photos/scolirk/4737109224/in/set-72157624245224937

We filled up a lane, blocking traffic, carrying banners, drumming, sometimes singing. I was nervous.

I had never before participated in an illegal demonstration, and I felt a little out of place every time I found myself next to one of the bicycle-helmeted anarchists among the crowd.

What made the parade illegal was the organizers’ decision to forgo the mandatory police escort. The march was, after all, a protest against police brutality. But I kept glimpsing the noses of police cruisers cleverly parked in alleys or behind dumpsters along our route. They kept an eye on us.

It was my friend Jackson Nahayo – or what happened to him – that prompted me to publicly break the law in the middle of a Winnipeg street. Until then, I had always felt safe and comfortable on the good side of the police. I’ve called the cops before; the ones I met were mostly courteous and helpful.

Nahayo escaped a civil war in Burundi as a child and immigrated to Canada as a young man. Here he found safety and opportunity. He’s confident, but with a quiet intensity

that causes others to stop their conversations and listen to him.

Nahayo left his girlfriend’s house at about 2:00 a.m. on July 19, 2009. He was driving her white Cadillac and he pulled over into a 7-Eleven parking lot to give her a call. Minutes later a police cruiser pulled up next to him. As Nahayo remembers it, an officer approached his window and said, “What the hell are you doing here?”

Nahayo left his girlfriend’s house at about 2:00 a.m. on July 19, 2009. He was driving her white Cadillac and he pulled over into a 7-Eleven parking lot to give her a call. Minutes later a police cruiser pulled up next to him. As Nahayo remembers it, an officer approached his window and said, “What the hell are you doing here?”

Nahayo was instantly nervous. He’d been spot-checked by Winnipeg police before, simply because he was a black male driving a nice car in a downtown area. Given his childhood experiences, authority figures with guns at their hips made him edgy.

“Keep your hands where I can see them,” said the officer. Moving slowly, Nahayo turned on his cell phone and told the officer he was going to record the conversation for his own safety. I’ve always known Nahayo to speak politely; I have no doubt that he did so then. In intense situations he chooses his words carefully and his voice drops by a few decibels.

Later I helped Nahayo write his statement describing what happened. What follows is his account: The officer snatched the phone out of Nahayo’s hand, twisting his thumb, and immediately radioed for backup. Suddenly the parking lot seemed to be full of police cars, jostling like ice floes.

Shouting at him, officers surrounded Nahayo’s car. One got into his passenger seat and began roughly searching his vehicle and his person. When Nahayo yelled for help the officer turned his attention from the glove compartment and began to punch Nahayo in the ribs and hit his shoulder with an open palm. “A lot of your kind are criminals,” Nahayo remembers the man saying to him. Finding nothing, the cops took off.

Nahayo was left alone, uninjured, but shaking and in tears. A few days later he filed a complaint with the Professional Standards Unit, the Winnipeg Police Service’s internal body that investigates complaints against the police.

Months later Nahayo received a letter two sentences long. Your complaint “is not sustained,” it said. The only witness in the parking lot had been the eye of a 7-Eleven security camera. Police had seized the tape.

When Geez contacted the Winnipeg Police Service and asked for their side of the story, spokesperson Jason Michalyshen said he couldn’t provide any details beyond the fact that officers were investigating a call in the area.

![]()

It isn’t hard to find documented cases of police misconduct. Toronto police officers are facing criticism for violence used on protestors at the recent G20 Summit; Adam Nobody was left with a broken nose and shattered cheekbone after his arrest. In November 2010, an RCMP officer in Edmonton pled guilty to assaulting a prisoner in his care after video footage showed him smashing the man’s head repeatedly into a brick wall. In March, 2009, Roanna Hepburn wrote Winnipeg’s police chief a letter in which she described police taking turns punching and kicking her 18-year-old granddaughter in the stomach while she was handcuffed in a holding cell, all the while calling her a “dirty Indian.”

Nahayo’s experience introduced me to a side of the police I had never encountered. I began my research for this article with a list of interviewees and a sheet of questions. At the top I wrote: “Do we need the cops?” I wanted to hear people’s views about whether incidents like these result from a few “bad apples” or if there’s something fundamentally wrong with the system.

An article about the cops needed a cop’s perspective, so I met with Bruce Day, a retired constable with 20 years of experience in the Winnipeg police force.

Day has a round face, a tidy moustache and a ready laugh. He was eager to tell me tales of high-speed car chases and attempts to mollify belligerent drunks. But he also answered my questions about racism and violence. “Honestly,” Day said, “there is no systemic issue such as racism or overzealous police.” If you break the law, he continued, you’re going to get arrested, whatever your race. We don’t care who you are.

Taking and administering a few bruises is just part of the job, he added. “When you get in a high-speed chase, and I’ve been in about a dozen, the adrenaline is up to here. You’re driving through red lights and your life is hanging by a thread . . . and then you catch the guy. He gets a licking because he put my life on the line. . . . Nothing is done to the point where you smash his face into the brick, but does he get a little cuff here and a cuff there? Absolutely!”

Day also told me the pressures of the job are severe. New cops are terrified they’ll screw up. They constantly risk their physical safety and people will resist arrest with guns, knives, teeth and nails while police officers have to play by the rules. When adrenaline runs high, he said, good judgment doesn’t always prevail.

Day also told me the pressures of the job are severe. New cops are terrified they’ll screw up. They constantly risk their physical safety and people will resist arrest with guns, knives, teeth and nails while police officers have to play by the rules. When adrenaline runs high, he said, good judgment doesn’t always prevail.

What startled me the most about Day’s world was that all the characters seemed to easily sort themselves into “good guys” and “bad guys.” Sure the good guys screwed up from time to time, but the bad guys probably had it coming.

I left the interview mulling over two things: the police and their critics are separated by such a wide cultural, philosophical and experiential gulf that I couldn’t conceive of the two sides ever hearing each other; and cops have one hell of a stressful job.

![]()

My next few interviews helped me understand something about the people who aren’t served by the police.

Doug King is a lawyer with PIVOT, an organization that does advocacy work for residents of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. King confirmed what I had heard – that Vancouver police effectively corral crime, poverty and drug use in the Downtown Eastside by heavily patrolling its borders while ignoring minor crimes like drug possession within the area.

King described the relationship between the Vancouver police and most local residents as adversarial. “Because people are using illegal drugs, the police tend to see them all as doing illegal activities, and that’s the start of their relationship,” he explained. “The police seem to have the mentality that everyone in the neighbourhood is guilty.”

PIVOT has made numerous attempts to try to restore some trust between Vancouver police and Downtown Eastsiders. A few years ago PIVOT collected accounts of police brutality and illegal search and seizures, wrote up 50 affidavits, presented them to the Vancouver police and asked for an investigation. Eventually PIVOT dropped the claims in exchange for police participation in a dialogue PIVOT hoped would lead to an attitude shift, but so far there are only “glimmers” of improvement.

Trust is non-existent, said King. Many aboriginal residents of the Downtown Eastside still remember police forcing them into residential schools. How can you trust the police when you’ve suffered violence at the hands of the state as long as you can remember, he asked. “It would be silly of us to expect that.”

And it isn’t just drug users who are illegal, pointed out Les Sabiston, a volunteer who works with a grassroots organization in Winnipeg called Copwatch.

Police have carte blanche to badger homeless people for sleeping in front of stores or urinating in public. “Their bodies are regulated constantly,” Sabiston said, explaining that when public property is your only home and you self medicate with alcohol, your whole life becomes illegal.

Elizabeth Comack, a sociology professor at the University of Manitoba, is writing a book based on 78 interviews with aboriginal people about their encounters with the police.

Over and over again during the interviews, Comack listened to aboriginal men tell of being stopped and questioned by police because they “fit the description” of a suspect. Usually that description sounded like: “aboriginal, male with a ponytail and bluejeans.” Some men said this happens to them regularly.

“Stop to think about that,” said Comack. “If that became part of your routine, that’s quite stunning.”

Stories like these don’t surprise Leslie Spillett, executive director of Ka Ni Kanichihk, an aboriginal youth leadership organization in Winnipeg. In Canada the police have historically been part of the project of cultural genocide, she said. The Northwest Mounted Police and the RCMP removed aboriginal people from their land, arrested their leaders for practicing their spiritual traditions and forcibly took their children to residential schools.

“How do you repair the damage that’s been done?” Spillett said.

She sees the western system of policing as culturally alien to an indigenous view. Traditionally First Nations communities would share responsibilities for security and justice among their members.

But it’s not fair to blame everything on the police, said Spillett. The police are only one part of a colonial system designed to condition superiority and inferiority complexes into different segments of the population. Our health, education and justice systems all need to be reformed. A few days of diversity training for cops won’t do the trick, said Spillett. “If you have cancer, one chemo doesn’t do the job.”

![]()

The harsh reality of our society is that we’ve set it up so we need the police. We’ve handed them the sole right to use violence on our behalf, Doug King told me. Even his clients in the Downtown Eastside need the cops to intervene when their landlords hire thugs to rough them up.

Unfortunately, the police aren’t equipped to solve problems of crime – only to control them. Bruce Day was the first to point that out to me. It only took him a month on the job to realize he wasn’t “solving” anything.

Manitoba and Saskatchewan have the highest crime rates in Canada; the two provinces also have more police officers per capita than any other province. Conversely, in New York City, where tight budgets have been steadily shrinking the city’s police force in recent years, crime is down more significantly than most other American cities.

Manitoba and Saskatchewan have the highest crime rates in Canada; the two provinces also have more police officers per capita than any other province. Conversely, in New York City, where tight budgets have been steadily shrinking the city’s police force in recent years, crime is down more significantly than most other American cities.

It’s too simplistic to say that more police lead to more crime, but maybe instances of police misconduct aren’t problems so much as they are symptoms. To use another analogy: maybe it’s not a case of a few bad apples, perhaps the barrel itself is rotten.

![]()

Where does this leave me? The answer is: dependent upon an unjust and ineffective system that perpetuates my own privilege at the expense of others. Even if one existed, a non-violent police force wouldn’t solve this problem. Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr. drew attention to the restraint exercised by police officers who had handled protestors nonviolently. “But for what purpose?” he asked. “To preserve the evil system of segregation.”

Josiah Neufeld lives, writes and rides his bicycle in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

1 Comment

Sorry, comments are closed.

Josiah – the title for your article is misleading. Your argument is not about whether we need police, but about the realistic challenges cops face because of our colonial past and issues of discrimination.

To suggest that we’ve set up society “so that we need the police.” is a vague, massive generalization. My first reaction to reading this sentence was – can you imagine ANY society on earth which has no crime or needs no use of force? Or do you think it is possible to “set up” a society in which crime is nonexistent? If I were you I would temper some of your comments with a dose of realism. The professor of sociology refers to First Nations communities as sharing “responsibility for security and justice” but says nothing about how this was done.

Second, you suggest that we collectively are the cause of crime and therefore police. I’m not sure who you mean by “we”. There are a couple hints at the capitalist/colonialist alliance as structural causes. By blaming “we” as a systemic cause, there is just as much logic in saying that we should get rid of ourselves as there is in saying that we should get rid of police – a mere symptom.

Finally, King Jr’s quote is a nice rhetorical flourish but can be used as an argument FOR police. King understood that unjust laws were not true laws (according to his view of natural law, with its roots in classical and medieval philosophy). Police and laws were being used to support an unjust regime. But what happens when the laws and system DO become just? King Jr. obviously has high regard for the rule of law, and that is why he wished to see unjust laws changed. King did not view police or rule of law as a menace, but in need of reform. Getting rid of police is the opposite of a high regard for the rule of law.

Andrew winnipeg May 15th, 2012 5:03am