Admit defeat, then engage

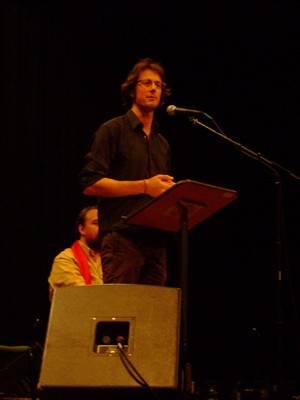

Paul Kingsnorth speaking at the Dark Mountain Festival.

Credit: Paul Kingsnorth, https://www.flickr.com/photos/naturewise/4660379501

An interview with Paul Kingsnorth [Excerpt]

Paul Kingsnorth is an author, poet, father, husband, and most recently a small landowner in Ireland. He previously served as the deputy editor of The Ecologist. Kingsnorth’s first book, One No, Many Yeses, chronicled the anti-globalization movement around the world. Real England: The Battle Against the Bland, published in 2008, returned Kingsnorth’s focus to his homeland.

In 2009, Kingsnorth co-founded the Dark Mountain Project, a collective of artists attempting to tell new stories about the destructive civilization we inhabit; five anthologies have since been published under the banner. He authored two significant and controversial essays for Orion magazine, published a year apart from each other, titled “Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist” (2012) and “Dark Ecology” (2013).

Last year, his debut novel – titled The Wake – was released. Told in a “shadow tongue,” a derivative of Old English, it tells the tale of a group of guerrilla fighters that emerge following the conquest of England by Norman forces. In April 2014, the New York Times Magazine published a much-discussed article about Kingsnorth titled “It’s the End of the World as We Know It … and He Feels Fine.”

How’s Ireland treating you?

Good. We’ve only been here five or six weeks, so we’re still settling in. There’s a lot to do. We’ve got a few acres of land, so we’ve kind of jumped into the deep end, doing everything at once, at the time of year when everything starts growing. It’s got quite interesting. We’re busy, but in a good way, hopefully.

Why’d you decide to move, given your own personal attachment to where you grew up?

It’s been an interesting one, actually. I’ve had to sort of chose between a way of life that I wanted to have and the country that I lived in and came from. I do write a lot about England and Englishness, just because it’s my place, not because it’s any better or worse than anywhere else: just because it’s my place and I know it; it’s in me, and it’s my culture.

There was a particular kind of way that we wanted to live that would allow us to only do work we thought was important and have as little impact as possible and bring our kids up in a certain way. And it’s just not possible to do in England, because it’s so expensive now. It’s hit a certain sort of path of a capitalist psycho where there are so many people and a housing crisis and the level of growth is insane.

Ireland’s a smaller country with far fewer people and less pressure. It’s got its own problems – of course, as all countries do have. So I could either stay in my homeland, if you like, and live in a way that I didn’t want to live, or I could come somewhere else and live as I did want to live. That was the choice I made in the end.

Ireland’s a smaller country with far fewer people and less pressure. It’s got its own problems – of course, as all countries do have. So I could either stay in my homeland, if you like, and live in a way that I didn’t want to live, or I could come somewhere else and live as I did want to live. That was the choice I made in the end.

A common response I’ve seen to your writings is the conflation of withdrawal or the admittance of failure with giving up. Have you experienced much of this with your work with the Dark Mountain Project?

The only issue that we have at Dark Mountain periodically is with a few environmental activists – particularly climate activists – who read what we’re doing and writing about it as “giving up.” And we see a lot of this. There was a bit of a wave of that in response to this New York Times piece as well, particularly because that was the kind of aspect of things it chose to focus on: this kind of walking away from activism because it’s not going to work, which is only really one aspect of what I do and write about, and I haven’t really written much about that for quite a few years.

It was something I wrote about at the start of Dark Mountain, because it was kind of one of the things that precipitated me to that point. I still think that’s true, and I still think that it’s too late to stop climate change, and massive environmental activism is just failing: it’s very unsophisticated. I don’t think that we can use the tools of ’60s radicalism to fight a war against ourselves and save the planet. I don’t even think the narrative that we keep hearing from activists about fighting or giving up is even a useful way of looking at the world, as if it’s a giant war.

Sometimes, I get the impression that people think they’re in an episode of Star Wars and they’re the heroic Jedi fighters and they’ve got to bring down the evil empire, and how could you possibly walk away from this heroic struggle. The number of times I’ve had Martin Luther King, Jr. and Frederick Douglass quoted at me by people who are basically spending their lives blogging is amazing.

If you’re fighting against climate change, you’re fighting against yourself, because we’re all part of that. I don’t feel like I’ve given anything up, other than certain forms of political activism that I thought didn’t work and in some cases are causing as much damage as they are doing good. This carbon obsession that mainstream environmentalism has is leading it to destroy a lot of wild places with industrial technology in the name of sustainability. I don’t think that’s sustainability. It’s certainly not environmentalism, as I understand it, so I don’t want to get involved in it.

As far as I’m concerned, I’m doing more than I’ve ever done. This thing about moving here isn’t about giving up, it’s about re-engaging for me. I’ve got two-and-a-half acres of land, and I’m going to manage it in a way that’s good for my family and the ecological community here and it’s good for the wildlife. I’m going to learn to engage with an actual real environment instead of just talking and writing about the environment in general terms. I’m going to re-engage with the world.

I recently read and reviewed a collection of letters between Gary Snyder and Wendell Berry, which they’ve written over the last 30 years. It’s a very, very interesting book. They talk a lot about this, because they’re both farmers and both manage land in very different ways. They talk a lot about this kind of balance between your personal engagement with a plot and place and a bigger perspective. Wendell Berry, in particular, talks increasingly about the sort of emptiness at a lot of environmentalist narratives, where there’s lots and lots of talk about the environment from people who aren’t engaging with it on a practical level. He says, “look, if you can’t actually engage with a piece of land and get your hands dirty and understand what compromises you have to make in order to feed yourself and balance that out with what the rest of nature needs and the rest of it, then you can’t really much about nature, because that’s what it is.”

As far as I’m concerned, I’m actually engaging myself with what I’ve also been concerned about, at a local level. I’m also continuing to write and work on Dark Mountain, which is also action. I do find it very interesting that some people don’t think writing is an action, as if writing an essay, putting it out into the world, and influencing or informing or interesting people is not an action. It’s just somehow a non-thing, and the only thing that matters is going on a march with Bill McKibben.

I’ve been reading a bit of Albert Camus lately, and I’ve found his perspectives on art as a way to rebel against the absurdity of monotony and powerlessness and eventual death really intriguing. In The Myth of Sisyphus he wrote, in a phrase I quite enjoy, that “the [absurd] work of art is born of the intelligence’s refusal to reason the concrete. It marks the triumph of the carnal.” Do you see the role of your own art and that of Dark Mountain in similar terms?

The full version of this article only is available to subscribers. Please subscribe to get 84 pages of Geez sent to your door for only $35/year (4 issues).

Sorry, comments are closed.