A Catastrophic Uncovering

Credit: Suzie's Farm, https://www.flickr.com/photos/suziesfarm/7684394682

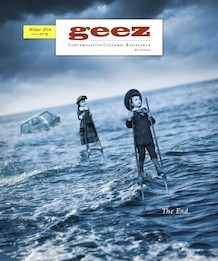

Between this September’s ineffectual UN summit on climate change, the ongoing crises in the Middle East, and the steady barrage of apocalyptic thrillers coming out of Hollywood, the demise of human civilization has eked its way into a lot of minds lately.

We’ve all heard the projections: if we don’t reduce a certain something by a particular date, a vaguely catastrophic trend will become “irreversible.” Ocean temperatures are rising and finite resources are depleting. By all accounts, we’re totally screwed.

Yet somehow the statistics aren’t sinking in. Politicians refuse to make commitments that would slow down the economy, and a wholesale abandonment of the myth of progress is just not in the cards.

Don’t get us wrong, it’s probably for the best that ecocide has entered popular consciousness. With protests, rallies, and bans on absurdities like cosmetic pesticides and plastic bags, we’re starting to see hints of a move in the right direction. But, as long as the thrust of popular environmentalism remains “what will it take to sustain our way of life” rather than “what sacrifices must we make to enter into a symbiotic relationship with our biosphere,” we’ll continue our sociopathic spiralling.

It’s time to admit it: wind farms and electric cars aren’t going to save us. Politicians and their economists won’t do it either. And the recently invented god of rapture theology is not going to pluck us, the chosen few, from his sinking ship. After all, we’re the ones who set it aflame.

It’s time to admit it: wind farms and electric cars aren’t going to save us. Politicians and their economists won’t do it either. And the recently invented god of rapture theology is not going to pluck us, the chosen few, from his sinking ship. After all, we’re the ones who set it aflame.

And yet there is reason for hope. As the Dark Mountain Project Uncivilisation manifesto puts it, “The end if the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop.” In this issue, D.L. Mayfield and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson put our ecological crisis in context by reminding us that the belt-tightening of the western world is hardly the first catastrophe of its kind. And, as several contributors have pointed out, the current climate catastrophe serves us by revealing the abusive nature of our relationship with the earth (the word “apocalypse” means “uncovering” in Ancient Greek). Like all addicts, we can’t begin to imagine a different life until we recognize and abandon the destructive patterns that define our lifestyles.

We’re not here to present a comprehensive apocalyptic ethic, but there’s one thing we can suggest: Start living now as if the end has already come, because in many ways it has. We, the colonizers and global rich, are just the last to see it.

Root yourself in your immediate community. Rely on your neighbours, and let them count on you. Learn about your watershed and local food system. Own fewer things, and buy second-hand. Spend more time outside and less time in front of a screen or steering wheel. If you have a faith, seek out its traditions of hospitality and reliance on the earth.

We’re not saying global collapse is a good thing. Without a doubt, there’s much suffering ahead. But, if we can acknowledge the calamity of our situation and refrain from despair, we’ll discover a life at once more sustainable and meaningful.

Thanks to all the writers, artists, and volunteers who contributed to this issue. We’d like to thank Josiah Neufeld in particular; he spent months constructing a piece that acknowledges the immense gravity of our situation while also providing a glimmer of possibility for change. His story of a couple that is living as if the apocalypse is already upon us serves as an anchor for this issue.

Tim Runtz is the circulation manager and associate editor of Geez magazine. He lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba where he also works as a bike mechanic. James Wilt is an associate editor of Geez, arts and culture editor of The Uniter, and a freelance writer living in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.