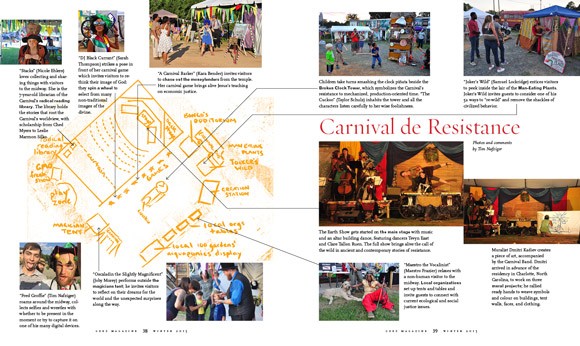

The Carnival Spirit Snubs the Voices of Civilization

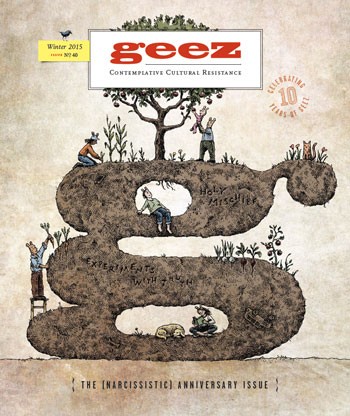

Carnival de Resistance in Geez, Winter 2015 Credit: Tim Nafziger

If life is a broken record and the only tune we play is the song of the empire, this past September I jumped out of the groove for 10 days when I joined a theatre troupe called the Carnival de Resistance.

See a big version of the Carnival spread here.

The Carnival is a project that has been experimenting in re-wilding in the way of Jesus since 2013, with month-long residencies in Virginia and a shorter presence at the Wild Goose Festival in 2014.

We call the Carnival a holy game. Our play takes us to the edge of our domesticated imaginations and beyond. In the midway, we become wild and mischievous characters that delight and befuddle passersby with magic tricks, fantastic costumes, carnival games, and improbable accents.

Joker Wild invites participants to take on feats that run against the grain of dominant culture. The Cuckoo, in her broken clock tower, speaks in paradoxical koans and exhorts the crowds to smash their clocks.

The Christian tradition has a 2,000-year history of folks inspired by the Jesus way to step outside of civilization. The desert fathers and mothers created space in the wilderness, far from the cities of the Roman empire. Celtic communities centuries later continued in the same stream, connecting their faith with the rhythms of the land where they lived.

In our demonstration village, Jon Felton and the rest of the crew masterminded a kitchen: they cooked food over a fire of sticks from the forest and washed dishes using a foot pump. It looked like a monastery kitchen from 150 years ago and led to creative troubleshooting around questions like how to heat dishwater and how to keep consistent cooking temperatures. We made some mistakes, but it was precisely the willingness to make those mistakes that poked holes in the box of everyday life.

In our demonstration village, Jon Felton and the rest of the crew masterminded a kitchen: they cooked food over a fire of sticks from the forest and washed dishes using a foot pump. It looked like a monastery kitchen from 150 years ago and led to creative troubleshooting around questions like how to heat dishwater and how to keep consistent cooking temperatures. We made some mistakes, but it was precisely the willingness to make those mistakes that poked holes in the box of everyday life.

One of the highlights of the Carnival for me was taking on a character that connected me with a deep, goofy part of myself. I was assigned to train some volunteers before the midway opened. A few hours into the evening, one of the volunteers confessed that he hadn’t recognized me with my funny hat, face paint, and funny voice. Success!

You might ask, “Don’t the imperial problems of ecological collapse and consumerism call for a more serious response than all this?” Having spent many years within movements that consider their ambitions as matters of life and death, I’ve determined that our seriousness is often part of the problem. We work long hours, driven by guilt and urgency rather than overflowing joy. The average non-activist can smell the intensity on us from across the street, and it isn’t always pretty.

Voices in our heads

Play and creativity are vastly under-appreciated tools for social change. Our imaginations have been contorted by our society in ways that are hard to undo simply by reading the right books or attending the right lectures. The voice of civilization is like an angel on our shoulder that coaches us to fit in rather than do what’s right. It whispers in our ear that we shouldn’t draw outside the lines and should, above all, avoid making mistakes. As I’ve come to understand the Carnival over the past year, I see how important it is to deal with these civilizational voices in our heads.

Children don’t have a problem with drawing outside the lines. My partner Charletta Erb is a marriage and family therapist; she notices the way children experiment with reality all the time. They observe models in real life, then role play and pretend without having everything figured out.

“It doesn’t matter if there’s no food for the house, they’ll eat invisible food!” she says. “No tools? Just grab a stone or a stick! There’s no waiting until all the right resources are purchased, the right education completed, or the right, like-minded friends come along.”

Musicians, writers, and other successful artists find ways to recover this playfulness. They don’t wait until all the money is saved or a detailed plan is ready to execute.

It turns out that the willingness to set aside the need to be correct plays an important role in our creativity. Musician and researcher Charles Limb has studied the brains of jazz musicians while they are improvising on the keyboard.

It turns out that the willingness to set aside the need to be correct plays an important role in our creativity. Musician and researcher Charles Limb has studied the brains of jazz musicians while they are improvising on the keyboard.

“Scientists found that a region of the brain known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex . . . showed a slowdown in activity during improvisation,” he said. “This area has been linked to planned actions and self-censoring, such as carefully deciding what words you might say at a job interview. Shutting down this area could lead to lowered inhibitions.” What if that part of the cortex is where the civilization angel lives, the same angel that implores us to refrain from screwing up?

As part of our Carnival rehearsal warmups we waved our arms, spun in circles, and made strange sounds. We would have been very out of place in an office cubicle, but we gave each other permission to stop listening quite so closely to that angel.

At its best, sacred play can help us look beyond a cultural blindness that limits and deforms our imaginations. We may even find ecstatic moments when we step back and see the kingdoms of the world stretched before as Jesus did in the wilderness. These moments often bring incredible insights and epiphanies that shake us to the core and force us to make watershed decisions in our lives.

Carnival de Resistance asks what would happen if we let subversive play leak into our lives. What if we come together to let our dreams shine through into reality? What if we let our imaginations get away from us?

Tim Nafziger lives with his partner Charletta Erb in the Ventura River watershed in Southern California and works with the Carnival de Resistance as development director.

Sorry, comments are closed.