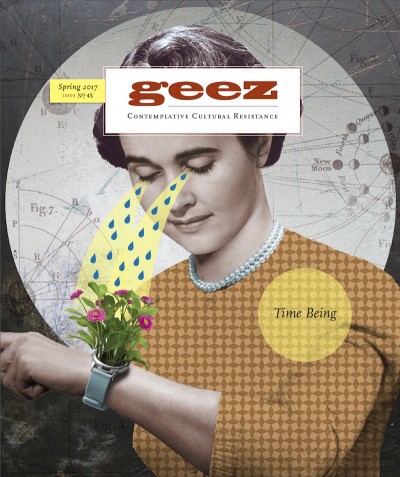

Some Write in Ten Minute Chunks

Dirty dishes in a sink. Credit: James White

I don’t have time to write an essay. I don’t have time to outline my points, think of a snappy ending, or edit several drafts until it’s ready for submission. Rather than staring out my window while I let ideas take shape I should be washing last night’s supper dishes or running to the store to get toilet-bowl cleaner. But instead I give in to my craving, jot down the time, 8:43 p.m., and start scribbling.

At 8:57 p.m. I look at the clock. It’s been a little more than 10 minutes and I now have the skeleton of the piece and a bit of sinew and bones of the first paragraph. I also know what I need to do next. I need to write for another 10 minutes, and then another 10 minutes after that.

The following morning I fire up the computer to pitch my story idea – writing an article in very short blocks of time – to Geez magazine editor Aiden Enns. After 13 minutes the first draft of my pitch is barely readable, but my time is up so I press save. At least I think I press save. A week later, when I go to work on the pitch again, I will realize I didn’t save my draft at all. I sent it – misspellings, run-on sentences, and all.

I am horrified but the irony doesn’t escape me. Mistakes like this are one of the casualties of working with scraps of time. Ideally, I would love to retreat to a cabin in the woods where I could sink my teeth into a project but that is not my reality.

My reality is working with stolen moments and facing the same old arguments every time I sit down to write: You don’t have time for this, and Why start something when you can’t finish it, and Wait until next week or next month or next year when you will finally have the time you need.

But I’ve learned that these voices eventually grow dim, not because I always finish what I set out to do, and certainly not because what I’m creating is perfect, but because I’m engaged enough to see what I need to do next – whether it’s fleshing out an image, editing a clumsy sentence, or drafting a new piece. And when I listen to my work instead of my insecurities, I know I don’t want to wait for a mythical surplus of free time before I practice my craft.

Brenda Ueland writes in If You Want to Write: A Book about Art, Independence and Spirit (1938), “There is something necessary and life-giving about ‘creative work’. . . . And it is like a faucet; nothing comes unless you turn it on, and the more you turn it on, the more it comes.”

Words do not appear on the page without someone picking up a pen, nails do not drive themselves unless someone wields a hammer, and inspiration does not flow unless we are open to it, if only for a few minutes at a time. Sometimes we need to “turn on the faucet” even when we don’t know exactly what we will do with the flow. Turning on the faucet requires enough courage for the one little step in front of us without figuring out all the details before we make a leap of creative faith.

One Saturday morning, my husband and I lugged our old dining-room table out to the curb. I hated to get rid of it (it was the first piece of furniture my grandpa had purchased after immigrating to Canada in the 1940’s) but it was too small and falling apart. We taped a “Free” sign on it and then, not a half-hour later, I watched my husband haul it back to our garage. I raised my eyebrows, and he said, “It’s maple,” to explain his change of mind. And then, “Maple would make a good banjo.”

At that point he wasn’t thinking about the fact he didn’t know how to play the banjo or that he’d never built an instrument before. He wasn’t thinking about the hours he’d spend routering, gluing, clamping, shaping, and sanding the wood. What he was thinking about was the thing he needed to do next; cutting the table into two-inch wide strips.

To make music from a piece of maple you don’t need to clear your schedule for days at time or spend hours preparing yourself, you must only be willing to haul a rickety table back from the curb.

You cannot know what you need to do next if you don’t start with the first 10 minutes. Using these moments is a brave and important act. After all, life-changing decisions and critical deals can be brokered in 10 minutes. In 10 minutes you can pull a trigger and destroy a life. In 10 minutes you can make love and conceive a child. In 10 minutes you can plant a tree that will shade your great-great-grandchildren. In 10 minutes you can decide to build a banjo. And in 10 minutes you can write down the first sentence of your next story.

(Author’s note: This article was pitched, drafted, re-written, and submitted in 15 short sessions, ranging from 10 to 20 minutes at a time.)

Tricia Friesen Reed is an educator, writer, and founder of Wonderscape Retreats (nature-based creative arts retreats). She loves to see others discover their creative potential and her own work has been published in literary magazines and on her blog: experimentingaswegrow.wordpress.com. Time slows down for her when she’s got her hands in the dirt or on a keyboard.

Image: cc, James White, Flickr.com

Sorry, comments are closed.