Eating Together Takes (a long) Time

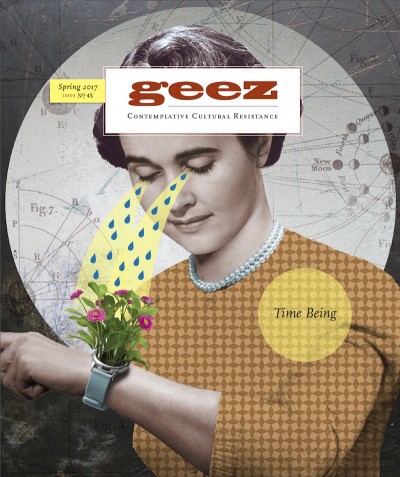

Big calm... Credit: nicoletta antonini

We wait, yes, but while doing something else. . .

We wait, yes, but while maximizing the time in order to avoid boredom. . .

We wait, yes, but we fill time in order not to feel the weight of time.

Every day, after our public liturgy in the church, we move silently into the interior personal space of the refectory for the liturgy of the table.

The refectory is bright and simple, peaceful, illuminated by a great deal of natural light, with wooden tables arranged in a U-shape.

The prioress has her spot, right beneath the icon of Christ on the cross. Two sisters are assigned to serve each week, and two are assigned to read.

We stand in silence behind our stools as we wait for everyone to arrive. This can take some time. Once we are all gathered, a sister sings a refrain of thanksgiving, repeated by all, the prioress reads from her book of blessings for that day, and we sit.

The two sisters assigned to serve read a short excerpt from our Community’s Livre de Vie in French and in another language. During this time, we wait; we don’t pass any food around, we don’t fill our water

glasses, we don’t take bread from the bread baskets. When the short reading is finished, the servers begin to pass the dishes, and the readers pick up reading the current book where we had left off the previous day. The prioress, at the head of the U, receives the entrée (salad, etc.) in two dishes which she offers to the person on her right and on her left, respectively, before taking a portion herself, and sending the serving bowls down each arm of the U.

Sisters offer each other water when their glasses are empty. Sisters offer each other bread from the bread baskets. It’s each person’s job to keep their eye on their neighbour’s water, to make sure she is not silently perishing of thirst.

Before a course of the meal is served a second time, and before a new course is introduced, we wait until everyone finishes eating. Those on each side of the prioress wait to serve themselves until they are offered the second course. The prioress keeps an eye out for the pace of things, and ultimately– once she sees that everyone has finished their last course (fruit, normally) – is the one who signals the readers, with a nod of the head, that it’s time to stop.

When the reading stops, we stand, a sister sings a short refrain which is repeated by all, we cross ourselves, and then we silently carry our dishes to the kitchen where we clean up together, in silence. Afterward, we move back into the refectory and seat ourselves around a wooden table for tea and a conversation of 20-30 minutes – if it is a Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday or Sunday. Here, we wait too. There may be 20 people sitting around the table, and yet one person will talk at a time: the rest listen and ask questions.

Conversation ends by the ringing of a little bell. We wash the cups in silence and then retreat to our cells for lectio divina.

These rituals that I have just described – our liturgy of the table – resemble in broad strokes the way that monastic meals have been taken since the 6th century. There is a deep symbolism to many of the things that we do, traditions that come from Judaism and the first centuries of Christianity where religious practices and shared meals were merely moments in the same ritual events. However, no one ever explains that to you explicitly. No one ever tells you what the point is, of eating this way. You come into the community, and you learn the dance. As time goes on, you slowly unravel the mystery of this dance, the symbolism of the service, and what these gestures are designed to do for you. You learn how to pay attention to your sister’s water glass, you learn how to pay attention to how much food you take, in order not to deprive the person sitting further down the U, you learn how to pay attention to the reading and not to your own wandering thoughts.

This sacred ritual, eating dinner, usually takes place in monasteries that are enclosed. This means that the majority of people in the world who eat this way, today, are those who have expressed a desire to live this way permanently.

Our community is very different, in this respect, because we welcome guests to our table three days per week – our family, our friends, people we have met at work or on the metro whom we want to get to know better. For this reason, as I was preparing to write an article for Geez about time and monastic meals, I sent around a questionnaire to my Mennonite friends who had come to eat with us in the past, soliciting their reflections – how is eating with us different from your normal rhythm? Would you want to eat this way every day? I also asked my sisters for their reflections on their first experiences of monastic meals, or about watching their families and friends eat with us.

Very few had very much to say about time. I was surprised. For me, one of the most noticeable differences between our meals, and the way I ate before I entered, is that we do a lot of waiting: to me monastic meals often strike me as slow and inefficient. It was in starting to ask people questions, for this article, that I finally clued in to something that should have been obvious: if I spend a lot of time waiting, during our meals, it means that somebody else is rushing to keep up. Ah. Now I see: the second course hasn’t come around yet because the guest is still eating her tomatoes. In fact, the guest is looking a bit stressed out about the fact that she is still eating her tomatoes. Somehow I did not pick up on the fact, until I began asking questions, that on the other side of my boredom, somebody else was feeling pressure to keep up.

Upon further reflection, I realized that the rhythm of our life, the time of our meals, isn’t either fast or slow: it’s fast for some, it’s slow for others. It’s foreign to all of us, and uncomfortable for all us, but not in the same way. We are all brought into a common practice.

When I asked friends what they found challenging about eating with us, almost everyone said something about social expectations, about not knowing the rules and about that being uncomfortable, especially in silence. But they also remarked on the peace and calm of the experience. They commented on the warm light in the room, on the simplicity of the space, on the taste of the food, on their sense of being appreciated and welcomed. They want to come back, they want to bring their friends.

One friend commented, “I remember being surprised that the formality of the meal somehow made it feel more open and welcoming, if that makes any sense.” And as one of my sisters remarked, “In general, my family seems to be somewhat uncomfortable during our meals . . . but also seems to appreciate the calm.”

This was an interesting coupling between discomfort and peace, a curious paradox, but nevertheless very true. It is peaceful to eat with us, but it’s not a sleeping sort of peace: it’s a peace where all of your senses are required to be

active and at work, focused on the community.

On the other hand, for those who are too young to care about social expectations, it can be a sleeping peace. Recently, one of my friends came to eat with her three-year-old daughter. My friend had been concerned that her daughter would be unable to sit still and remain quiet. I reassured her that this is fine, of course, and actually a welcome break for us. But ultimately the little one took us all by surprise: she ate her pasta, then quietly climbed into my friend’s lap, leaned her head against her mom’s chest, and went to sleep. She didn’t wake up until long past recreation (tea time), and snored loudly all the way through our conversation.

When I asked about her daughter’s nap time, my friend remarked, “She is a super active little lady and very curious, and it was interesting watching her watching the sisters and trying to figure out this very different way of doing things. But I was just blown away by how without any fuss she was able to go right to sleep. Usually nap time is a real battle. . . . I think [it was a result of ] so many people being quiet and calm together.”

Our way of eating is greatly appreciated as sort of a novel experience of peace and beauty. However, most, when asked, remarked that they wouldn’t want to eat this way every day. The most common reason given is the importance of maximizing family meal times, or dinners with friends, as occasion to have conversation. Although many remarked on the depth and intensity of the non-verbal aspects of communication that come to the foreground, when eating together silently in this highly-ritualized way, they felt that it was too bad, at the same time, not to use every available opportunity to talk.

“When raising a family in 2016, meal time is a precious time to share and converse about our lives/schedule/the world around us,” one remarked. “Eating together is intrinsically a socializing activity,” said another.

Socializing, yes, but talking? Two little girls, aged 6 and 8, informed me that they always eat in silence at Montessori school; for them it was normal. And another friend, who works in remote northern communities as a speech pathologist, told the sisters a story, during our conversation after dinner. She said that once some southern speech-and-language specialists were counselling the Inuit to talk with their kids while they eat, to help encourage their children’s language development. Hearing this advice, the northerners laughed. When asked why they were laughing, they explained that this is a sort of joke they tell about folks from the south: they talk – “blah blah blah” – the whole time they eat, in order to distract themselves from how bad their food tastes. In Inuit culture, families eat in silence, this friend informed us.

We don’t talk, and yet our way of eating is social – intensely social. Our way of eating is so social that it makes everyone a bit uncomfortable. One smart friend observed “the silence heightens the ‘communal’ atmosphere of the meal. If having a regular meal with so many others, you would inevitably start a conversation with the two or three people near you, effectively excluding others from ‘eating with you.’ However, the silence means that you are constantly aware of how many others there are.”

I feel privileged and blessed, to be living my life in this shared time – this intensely shared time where we neither “maximize our time” nor “fill time” to avoid boredom, but seek to reorient time around attending to the One who lives in each of our hearts – in our own hearts, and in the heart of my sister whose water glass is empty.

Sister Amy Barnes (Soeur Aimée) is a novice with the Monastic Communities of Jerusalem in Montreal. She said “time seems to crawl from 2:45 to 3:00 in the morning on Fridays, but the rest of the time, it seems like I’m on a rocket ship that is speeding up day by day: years pass now in the space that used to be occupied by mere weeks or months.”

Image: cc, Nicoletta Antonini, Flickr.com

Sorry, comments are closed.