Raising off-line kids in a real-life world

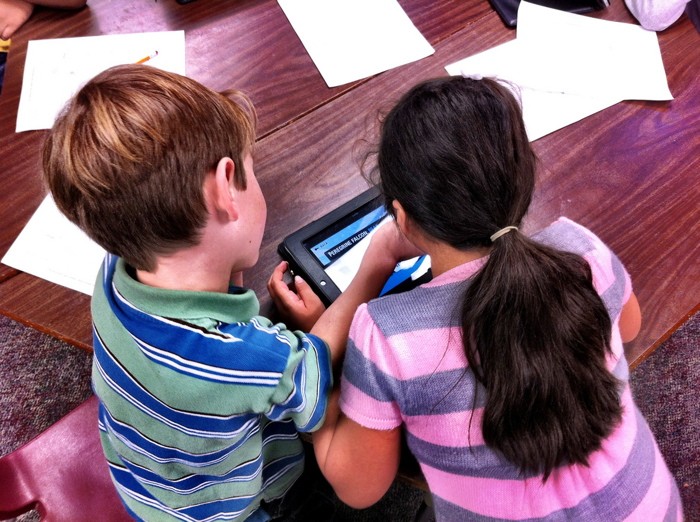

Credit: K.W. Barrett, https://www.flickr.com/photos/barrettelementary/6695935031

I was raised a television-starved kid, a deprivation arranged by my parents.

When television was everywhere in the sixties and seventies, my parents made the conscious decision not to buy one. Like so many stands against culture, that decision was subverted by the grandparents a few years later by the gift of a huge colour console.

I think those strong TV limits gave me a richer childhood and a more fulfilling adult life. Thanks to my parents, I grew up in an outdoor world and a tribe of relationships. Mine was a childhood of climbing, inventing, making, building. My four siblings and I now use TV and other screens very intentionally.

So as I raise my kids in a digital, webbed world, I am borrowing a page from that book. I work very hard to give my urban-raised kids time to grow up offline. I want them in love with the tactile, breathing world. I want them to have an imagination capable of trumping the “I’m bored, flick a button” response many kids exhibit. I am battling the peer who walks into our house to hang out, and seeing no screen in sight, has no idea what to do.

The apocryphal story in my family is a nephew, at age four, asking a neighbour kid over. “I’m not coming out. I’m watching TV,” his friend responded.

“Be careful,” warned my nephew. “Too much TV makes you forget how to play.”

But now that nephew is nineteen, in college, with a laptop and iPhone, and I can hardly catch him with one of his devices more than 10 feet away. We are fighting the long defeat.

I still stand behind the guidelines we used when our kids were 12 and under. They were not allowed to play computer games or watch movies when friends were over – we expected them to play in real, physical, and relational ways. I asked visiting kids not to bring over hand-held electronics. Screen time was rare; not an every day event. Computer time happened after chores, homework, and dark – and not every day. No cell phones. (The hardest sell – most of the kids in their urban classrooms have had cellphones since second grade.)

I still stand behind the guidelines we used when our kids were 12 and under. They were not allowed to play computer games or watch movies when friends were over – we expected them to play in real, physical, and relational ways. I asked visiting kids not to bring over hand-held electronics. Screen time was rare; not an every day event. Computer time happened after chores, homework, and dark – and not every day. No cell phones. (The hardest sell – most of the kids in their urban classrooms have had cellphones since second grade.)

Yet culture is a tsunami, bigger and more powerful than two parents, and I always knew we were only buying time.

The single most powerful force to push screen life on my kids was school. By seventh grade, teachers informed me that my child had to have an email account. The tsunami was upon us.

At 14, my son now attends one of the most innovative public high schools in our city, but it’s a one-to-one laptop school, and technology is how they roll. He was given his own machine and all school work happens online. With a two-bus-and-subway commute downtown alone, I also got him a cellphone, er, I mean a texting machine. (I can’t really change the fact that no kid will telephone another kid these days, and I don’t want him to be totally socially isolated from his new classmates.)

At 12, 75 percent of my daughter’s homework is online. While doing it, it is so easy to check email, look at kitty videos, and see what might be on eBay. (Our “simple living” ethic has made eBay my kids’ go-to when purchasing their own designer wear.) So in just a few years, our cyberlife has mushroomed, and I am looking for footholds to wield the tool well in these teenage years. I know enough not to let them have computers in their bedrooms, and I find that they are pretty wise about limiting their own computer use now. Every day, however, brings a new challenge to negotiate.

I am not anti-technology. I understand how the internet will be a life- line to my kids. They learn more with the web than I ever could with the set of encyclopedias my parents were so proud of. My son gets into Brown vs. Board of Education, where he can watch interviews, read papers, and find multimedia resources from all perspectives. He understands instinctively that there are many voices telling different stories, and has fine-tuned critical thinking skills. My daughter doesn’t get a math concept, and the Khan Academy teaches her more clearly than I could.

Technology helps level the playing field for kids with learning differences in ways that makes learning infinitely easier. It is vastly increasing the body of human knowledge by increasing cooperation and accessibility. It is amazing!

But there are downsides. While I would not argue that kids are less fulfilled creating a movie online than building a tree house outside, I do have an uncompromising bias. I want them to love trees, know their birds, and be able to grow food. These learnings are offline. We have all our lives to sit in front of our all-dominant screens and tap out our work and social interactions.

There is a growing body of evidence, from authors like Matt Richtel and Nicholas Carr, that our digital-age habits rewire our brains – specifically driving many of us into less focused, more distracted patterns of thinking. Research tells us that plasticity is an essential quality of the brain, which has rewired itself for centuries. But, during the critical period of neurological development, do we need to wire our kids for distraction?

There is a growing body of evidence, from authors like Matt Richtel and Nicholas Carr, that our digital-age habits rewire our brains – specifically driving many of us into less focused, more distracted patterns of thinking. Research tells us that plasticity is an essential quality of the brain, which has rewired itself for centuries. But, during the critical period of neurological development, do we need to wire our kids for distraction?

One bold elementary school principal I know asks parents whose kids are struggling with focus to put their kids on screen sabbatical. (“I want two months, but almost no parent is willing to do that!”) Within a few weeks, this single intervention leads to marked improvement in the student’s ability to focus.

For parents who worry that their kid will lose an edge: numerous studies demonstrate that kids with no or less screen time not only catch up with their screen-focused peers by mid-teens, but tend to use computer technology more distinctively as a tool instead of mainlining it like a craving. I find this to be true with my teenagers.

As parents, we can be as unconscious or resistant as the kids in disciplining life on the screen. Many parents see no potential problem with incessant monitoring of phones and iPads. We ourselves spend too much time in virtual, online worlds. If we are in denial about some of the more negative consequences of screen-dependent living, we can hardly help our kids find a healthy balance.

Recently, I was at a gathering which included five kids who hardly knew each other except that the same group had gathered a year previously. That initial gathering, the kids were wary, but soon played together like old friends. The next year, the other parents had backup in the form of an iPod, a smartphone and an iPad. Soon, every one of the five kids had retreated to a corner – into books or screens. On parting, one of the parents drew me aside. “I’m so disappointed S. [her son] didn’t play with your kids. They had such a great time last year!”

I stared at her, then mumbled something polite instead of my judgemental-yet-incredulous, “What do you expect when you bring an iPad along?”

At issue is how much our kids get to withdraw to their own solitary play world rather than grapple with the relationships and interactions around them. We learn to be community by participating in relationships we neither tailor nor choose. One consistent piece of feedback I get about my kids is that they are “conversational.” Initially, I found this odd, but soon I began to observe how many youth I now encounter retreat into their hand-held devices, disinterested in any social engagement. Because we have always expected our children to be part of the discussions around them, they are. This is perhaps the biggest difference between online life and real-world life: our online life is infinitely tailored to us. Our electronic devices quickly learn to navigate to our favourite websites and post ads for products we like. Social media gives us our own chosen circle and feeds us the political jargon with which we resonate. No matter how isolated our viewpoint, the web will help us locate others who share the same view.

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory is a forty-question survey, which was administered to 16,475 current and recent U.S. college students nationwide between 1982 and 2006. The results indicate a steady rise in narcissism – a “positive and inflated view of the self.” Sixty percent of the students in 2006 exhibited higher levels of narcissism than in 1982. Many researchers believe that digital technologies around self-representation in a digital world (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, etc.) are the culprits. Communities, political and social, depend on some sense of the common good and a willingness to sacrifice for that common good. Narcissistic people create dangerous and destructive societies.

The old saying goes: “If you want to know what water is like, don’t ask the fish.” Soon, a digital sea will engulf every part of my children’s lives. My task now, with the few, fleeting years left me, is to offer them palpable ways to understand and carry the beauty of life outside that sea. We can only choose how we will live in a digital world if we know, love, and hold to the rich and different life outside of it, trembling just beneath our fingertips.

Dee Dee Risher is an editor and writer who lives in Philadelphia.

Sources: “Attached to Technology and Paying a Price,” by Matt Richtel; New York Times series: Your Brain on Computers; “Is Google Making Us Stupid,” by Nicholas Carr; Alone Together, by Sherry Turkle (Ba- sic Books, 2011); “Is Facebook Killing our Souls?” by Shane Hippes

2 Comments

Sorry, comments are closed.

Our experience is largely the same. For their first few years our kids had no screens in their lives. Gradually we let a few hours of quality public TV and reasonably educational electronic games in. I saw some benefits yet I also noticed that my ever-creative and engaged kids experienced a sort of mental lethargy after the screen was turned off, as if they’d temporarily lost their ability to have fun w/o screens. I also noticed that their screen-intensive friends had a more chronic difficulty playing——sometimes insisting that make-believe meant following exactly the lines and movements of Disney movies they saw all the time. Once the preteen/teen years arrived we still maintained some limits. As a homeschooling family we permit no screens on during the day.

Our kids laugh that they’ve been deprived of essential cultural experiences like memorizing every South Park episode (something they do their best to catch up on) but overall they agree that their minimal screen upbringing has provided them with lasting benefits. They’re always happy to help with household and farm chores (usually doing them with no prompting). They are self-taught in all sorts of hands-on skills, eagerly converse with people of all ages, and now in college they find themselves perplexed by their bored and screen-obsessed peers.

Laura Grace Weldon United States July 10th, 2014 4:57am

Found myself nodding in agreement as I read your article. I agree with you….imagination, creativity and independent thinking thrives in the “outside” world. I think the phrase I really zoomed in on, was when you said you use screens very intentionally. I think that is where the balance is found.

Bonnie July 17th, 2014 6:13am