Political Hope: Liberation Theology, Neoliberalism, and the Prison Industrial Complex

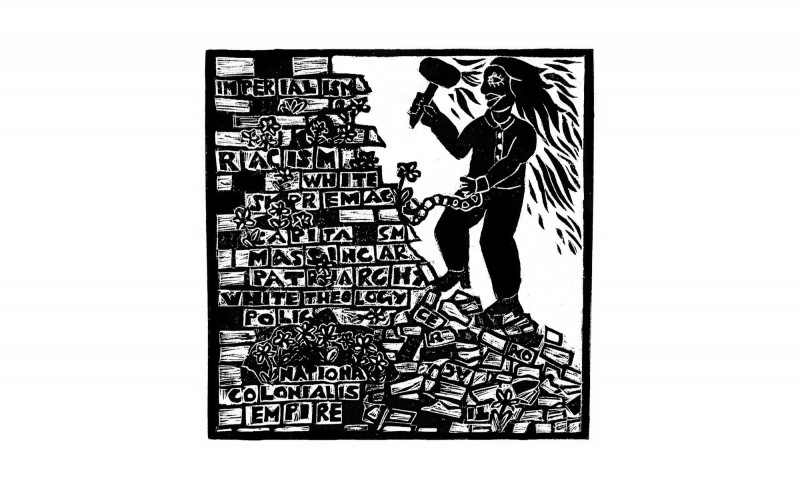

Becky McIntyre, “Dismantle the System,” May 2021, Linocut Print, 6 x 6 inches.

In the age of neoliberalism, political hope has been flattened into a campaign slogan, a simulacrum of change hinged on the silence and erasure of those voices and experiences that challenge grand narratives of “progress.”

Neoliberal political hope maintains itself by presenting solutions that rely on the hegemonic structures and ideologies of the present, and projecting them as innate features of the past and the future. For those of us with radical politics, political hope can look like complacency, naivete at best. And yet, our movements would cease to exist without utopian imagination. To that end, I find much political utility in underscoring the connections between liberation theology movements and the struggle for Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) abolition. Both demand the “end of the world” as we know it, and are sustained by generating utopian imagination from the margins in the service of present liberation struggles.

Latin and Black American liberation theologies held political weight from the 1960s through the 80s. These movements plucked salvation from its fixed position on the horizon, where it could be used to coerce and control populations, and instead folded it into present bodily struggles, igniting hope that could be put into the service of dismantling imperialism and poverty. These theological traditions put Christianity in conversation with Marxist political analysis and grassroots movement building.

The rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s was a direct backlash to these social movements, which had made significant gains in preceding decades. Neoliberalism is marked by the privatization of social welfare, loosened regulations on corporations, and globalization. These devastating social and economic measures have shaped the rise of the prison industrial complex (PIC) and the U.S’s devastating neo-imperial influence in Latin America.

The fact that liberation movements in Latin America and PIC abolition movements in the U.S. are inextricably connected cannot be overstated, especially when we begin to ask questions about how theology can assist in dismantling oppressive systems. The connection between these two movements underscores the importance of developing transnational solidarity in global liberation struggles.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes the rise of the U.S. PIC in part as a tactic of managing surplus land and laborers in the wake of post-war deindustrialization and globalization. Sweeping “tough on crime” bills criminalized poverty, warehousing and incapacitating racialized populations, particularly Black people and other people of color. Gilmore’s analysis of the PIC’s relationship to neoliberal globalization connects this struggle to the U.S’s interference with budding socialist movements formed in the wake of hard-won liberation struggles against colonial occupation in Central and South America. The U.S. capitalized on the political instability it created by outsourcing free and cheap labor with minimal state regulation.

Theology is only liberatory to the extent that it is grounded in these material realities. And yet: abolitionist activist and writer Tourmaline has pointed out that many engaged in the struggle to abolish the PIC are simultaneously enduring the spiritual and psychic wounds of racism, colonialism, ecological collapse, poverty, and gendered violence – so any meaningful response must be about more than just material conditions. Sanctifying the struggle itself gleans the spiritual nourishment required to sustain resistance to racial capitalism, while allowing radical imagination to inform present demands.

While liberation theologies have much to offer in terms of sanctifying struggle, these movements have also come with limitations. Mainstream liberation theologies in Central and South America had a relationship to the Catholic church that upheld the conventions of heterosexism and reproductive futurity. Paired with the belief that utopia (a concept which literally means “nowhere”) could ever be fully actualized, these theological movements made the mistake of allowing present injustices to shape their imagination of the future, rather than the reverse.

Queer people of color theorists and theologians, such as Marcella Althaus-Reid and Jose Esteban Muñoz, have worked with the tradition of liberation theology to unpair utopian futures from linear time. Rather than thinking of utopian futures as the last result of a culminating struggle, Muñoz’s work in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity applies queer temporality (which exists outside the traditional markers of time such as marriage, birth, and the nuclear family) to utopia, suggesting that it is found in glimpses and gestures in the past, present, and future. Thinking of utopia this way opens potential other ways of being and knowing in the world.

Because utopia in a radical context necessitates the end of the world as we know it, its relationship with apocalypse is not a binary one. Rather, their distinction is fraught, and underscores an understanding of reality as contextual. Althaus-Reid articulates the importance of temporally dislocating apocalypse from a fixed position in the future. For Indigenous populations, she says, “the end of the world” has already arrived in the form of mass genocide and ongoing colonial violence. Her approach to liberation theology does not seek to paper over the contradiction inherent in turning toward a colonial religion to resist colonial violence, but situates itself in this tension.

James Cone, author of A Black Theology of Liberation, wrote, “It was the African side of black religion that helped African-Americans to see beyond the white distortions of the gospel and discover its meaning of God’s liberation of the oppressed.” These theological interpretations are deeply concerned with the past – not as a means to co-opt resistance and obscure violence through the hegemonization of meaning, but through specific historical context, to resist grand narratives and the limits to radical imagination they impose.

The total abolition of the PIC requires imagining an otherwise, not just an absence of particular features of the present. It requires denaturalizing all those aspects of the social world that lead us to think prisons are necessary to keep communities safe. It is an ongoing struggle that necessarily refuses to offer a vision of abolitionist futures in their totality. This is particularly true when exacting justice in the present is at odds with the available methods of “justice” neoliberalism has to offer, defined in terms of legal human rights discourses. Abolitionists must evaluate to what degree we adopt a language for advocacy premised on a subject’s approximation to “humanity” as it is recognized by the state.

Hegemonic Christianity functions as a colonial religion that is weaponized to reify itself in the maintenance of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. For theologies to cease shaping people so that people can shape theologies, as Althaus-Reid and other liberation theologians suggest, we must interpret what we mean by “people” differently. We must create openings to deconstruct language that reproduces oppressive ideologies, such as “whiteness,” “humanness,” “normal,” and “abnormal.” A liberation theology that is by and for subjects we have yet to develop language for leaves openings for abolitionist futures we cannot yet imagine.

Miriam Vonnahme is a white abolitionist dyke living in Portland, Oregon. She recently graduated with a degree in Sexuality, Gender, and Queer Studies from Portland State University.

Start the Discussion