Can I Keep My Lewis and Tolkien?

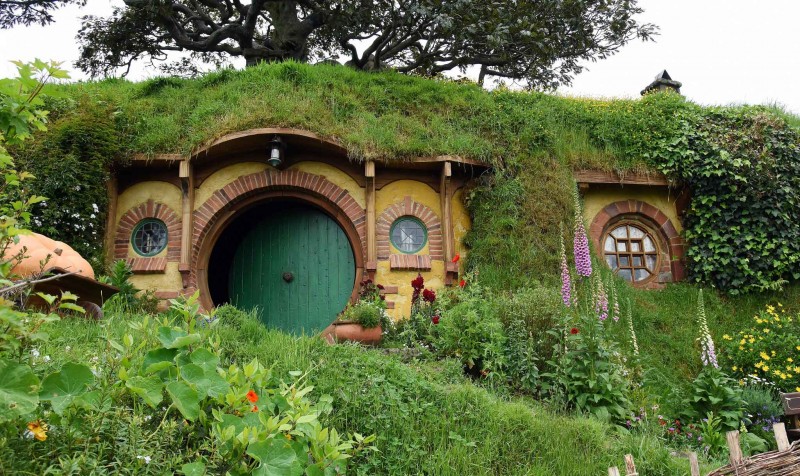

Harvey Barrison CC, “Bilbo Baggins' house as set by Peter Jackson for J.R.R. Tolkien’s _The Lord of the Rings_”, November 2018, Matamata, Waikato, New Zealand.

Like many bookish Christians raised in evangelicalism, I’ve read and re-read C. S. Lewis’ and J. R. R. Tolkien’s fantasy books countless times.

I went to graduate school for medieval studies partly because I loved the enchanted forests, idyllic villages, and lore-filled libraries of Narnia and Middle-earth.

But I soon learned of the long and troubling history of white supremacists claiming the Middle Ages as their own. The field of medieval studies was founded in 19th century Germany to preserve and celebrate the supposed noble heritage of northwestern Europe. In the centuries since, many Nazis, white nationalists, and QAnon supporters have looked to medieval Europe as a golden age of religious purity and racial homogeneity.

This view of the Middle Ages is patently false. In fact, medieval Europe was racially and religiously diverse. There were deadly bursts of anti-Jewish violence, but there were also times and places where Jews lived among Christians in relative peace. Christians wrote horrible things about Muslim “Saracens,” but Islamic philosophical texts helped shape much of medieval scholasticism. And pilgrimage routes to Rome and Santiago de Compostela were filled not only with Europeans but also African pilgrims from the kingdom of Nubia. (For more, see The Public Medievalist’s blog series “Race, Racism, and the Middle Ages.”)

Unfortunately, Lewis and Tolkien’s medieval-inspired fantasy worlds have more in common with the white supremacists’ idealized Middle Ages than they do with history. In both writers’ work, the good characters (such as Narnians, Hobbits, and Elves) are light-skinned, while many of the villains (like Calormenes and orcs) are dark-skinned. Lewis’ Narnia is a Christian state with a divinely appointed monarchy, while Calormen, its demon-worshiping enemy to the south, resembles an Islamic kingdom.

In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Aragorn is fit to rule Gondor partly because of his bloodline, which traces back to a physically and spiritually superior race of fair-skinned humans known as the Númenoreans. The name of their homeland, Númenor, comes from the Elvish word for “west,” and they are set against “Swarthy Men” of the east, who submit easily to Sauron’s rule. Even lower on the ladder are the evil orcs, whom Tolkien compares in a letter to the “Mongoloid” races. This essentialized racial hierarchy helps explain Tolkien’s popularity on alt-right forums like Stormfront. And, while Tolkien was vehemently anti-Nazi, he criticized Hitler in part for corrupting the “noble northern spirit” which Tolkien had “ever loved, and tried to preserve in its true light” – the same noble spirit that the earliest German medievalists sought to claim.

What does all this mean for those of us who love Lewis and Tolkien but who are also committed to dismantling white supremacy?

My answer also comes from the Middle Ages – or, more specifically, from justice-seeking scholars who study sexist, racist, and xenophobic medieval literature. These scholars don’t discard Chaucer’s or Dante’s works because of their harmful content. Instead, they show how literature and its readers can simultaneously reinforce and resist oppression. They point to internal moments of subversion, like Dante’s condemnation of avaricious priests, or external voices that tell a different story, like medieval women and Jewish writers.

We can take the same approach with Lewis and Tolkien. We can – and must – reject their books’ implicit white supremacy while also looking for resistance in the books themselves (like Lewis’ Calormen heroine, Aravis, and Sam Gamgee’s compassion for a dark-skinned warrior). We can keep them on our bookshelves while also seeking out fantasy novels that actively challenge white supremacy. We can allow the stories we love to disappoint us without ceding them to reactionaries.

Josh Parks is a freelance writer and editor with a master’s degree in medieval studies from Western Michigan University.

Start the Discussion