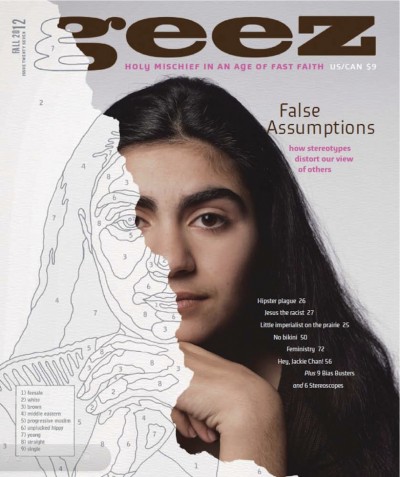

Jesus the racist

Finding transformation and liberation in unlikely places. Credit: Jim Crossley, http://www.flickr.com/photos/raindog/6918546476/

For years I have loved the Jesus of the Gospels who shatters social boundaries and cultural codes, who deconstructs the religious apartheid of clean and unclean, saint and sinner, powerful and marginalized.

Proclaiming and enfleshing the raw and wild reign of God, this dangerously off-script Messiah defies the sacred rules and definitions of who are the blessed ones, the sick, the sinners, the honoured guests. He embraces the leper, shares a burger with the drug dealer, affirms the gifts of women, subverts the wisdom of the holy authorities.

So it is with a profound sense of unease and even shock that I come upon that moral land mine of a story, Jesus’s encounter with the Syrophoenician woman (Mark 7:24-30). We might gloss over a lectionary recitation of the text and hear a nice healing story. But if we dare to pay attention to the details, this one can easily stick in the craw.

In Mark’s Gospel, which contains the most barbed portrait of the socially subversive Jesus, this story comes after a long debate with the Pharisees about cleanliness and uncleanliness (7:1-23). This debate is not simply about theological nuances or the specific daily practices of certain people – it has ramifications for the entire social order, because the division between what was clean and unclean underscored the identity of the Jewish people. Jesus is laying out the spiritual and ideological moorings of his social revolution.

To escape the heat of increasingly irate religious leaders, Jesus heads over the border into the Gentile territory of Tyre and Sidon. His desire for seclusion is foiled by a distraught mother, whose daughter is possessed by an unclean spirit. Mark stresses the woman’s social status: a woman, a Gentile, a Syrophoenician. Get it, readers? Her gender already renders her second class, plus she’s a foreign Other. And her family hosts an unclean spirit. She is triply unclean.

So what were you just saying about cleanliness and uncleanliness, Rabbi?

The exchange between Jesus and the woman is astonishing. He rebuffs her impassioned supplications, saying, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.”

Wait – did Jesus just call that woman a dog?

Some commentators have sought to soften the text by suggesting (absurdly) that Jesus is using an affectionate diminutive, like puppy. But texts from the time confirm that the term dog was a not-uncommon racial slur. The troubling fact is that Mark portrays Jesus using a demeaning racial stereotype of his day.

Just as startling is the woman’s response, in which she seems to accept the slur: “Yes, Lord; yet even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.”

Is she debasing herself to save her daughter? Or is she slyly challenging the Rabbi’s own blind spot, arguing that God’s liberation is not limited by ethnic boundaries? Is she shaming Jesus by confronting him with his own radical theology of “the least of these”? Jesus himself seems startled by her answer. He affirms her wisdom and faith, and, in typical fashion for Mark, implies that her bold spirit played a role in accomplishing her daughter’s healing.

I am drawn to the radical interpretation that this is a moment when Jesus himself is challenged, in the way he challenges others, to expand his sense of God’s reign and God’s action. The challenge comes from the margins, from someone on the other side of the divide between the clean and the unclean.

I wonder if, in a sense, this encounter is a two-way exorcism: the Syrophoenician woman’s daughter is freed from her unclean spirit, and an unclean spirit of residual ethnic chauvinism is cast out of Jesus.

I find a certain solace in such a reading. For all my supposed progressivism (living in the inner city, solidarity with folks who are poor and homeless, cross-racial work and community building), what demons of racism and classism linger in my psyche? Or how have I, while nobly crossing many social boundaries, unconsciously constructed my own paradigms of the Unclean Other (the conservative Christian, the one-percent Republican, the corporate elite)?

I find a certain solace in such a reading. For all my supposed progressivism (living in the inner city, solidarity with folks who are poor and homeless, cross-racial work and community building), what demons of racism and classism linger in my psyche? Or how have I, while nobly crossing many social boundaries, unconsciously constructed my own paradigms of the Unclean Other (the conservative Christian, the one-percent Republican, the corporate elite)?

Perhaps the most remarkable implication of the story is that it is the Other, the victim of our oppressive stereotypes, who holds the key to transformation and liberation. I, the messianic progressive white Christian, have to let myself be healed by the greater power of those who I often assume need me for their healing.

Like the deaf and dumb man Jesus heals in the next episode of Mark’s Gospel, when I hear Jesus call out to me, “Be opened!” I will be grateful for his words, especially knowing that even he needed to be opened a bit.

William O’Brien has been active in advocacy on issues of homelessness and poverty for over 30 years. He coordinates the Alternative Seminary, a grassroots program of biblical and theological study in Philadelphia (www.alternativeseminary.net).

4 Comments

Sorry, comments are closed.

Wow! I really love this article … not just the great use of words, but the way you build up your argument, the provocative ideas presented of Jesus being challenged by someone on the margins, even the way you make it personal not to the reader per se, but to yourself and thereby to the reader. Nicely jumps way past the usual trite explanations of this passage which I’ve heard over the years.

I did have one question: I can see some people objecting to the idea of an unclean spirit being cast out of Jesus, either in general or because this might be seen as implying that he has sinned. What are your thoughts on this?

rob g September 28th, 2012 8:27am

I don’t think there is any way to wriggle out of how uncomfortable this is given our traditional view of Jesus, but I believe Mark — who had no doubts about Jesus being the Christ come from God — is being very provocative in implying some kind of blindness on Jesus’ part. I think the language of “unclean spirit” might be better grasped in a symbolic sense, related perhaps to a vestige of ethnic chauvinism in the human Jesus as a Jew. It might not so much be a matter of Jesus being sinful. But note how open Jesus is in allowing that part of his worldview to be transformed — good news, and a role model for us!

Will O'Brien Philadelphia October 9th, 2012 1:38am

I interpret this passage in a different way. Jesus response to the woman is shocking, but it needs to be. His interaction with the woman in this way has two purposes. To bring her into the family of God and to teach the disciples who is welcome at the table.

In the Matthew account of this story, Jesus says nothing at first and waits for the disciples to ask him to deal with her – Jesus doesn’t intervene until everyone is fully engaged. Then, he approaches her and does not send her away as the disciples ask him to do. Instead, he puts forth an understanding that would shock no one, an understanding that EVERYONE (the disciples, the woman) would have about the situation – that she wasn’t a Jew and that in Jewish belief, the Messiah would come for the Jews. So, by asking his question, he is saying, “Let’s be clear about what you are asking here.” I’m sure the disciples felt some smug satisfaction by his response, though they probably were still wondering why he was engaging in conversation at all with the woman. They thought he was putting her in her place. In reality, he’s pushing her to challenge the notion of who is included at the table. She may have come looking for a crumb, a simple healing, a one-time exception to the Jewish rules of Messiah. But with Jesus’ bold words to her, he challenges her to want more. And in her beautiful response, she reveals both her need and her faith. She agrees that she is a dog, not worthy of eating at the children’s table. In the Matthew passage, she agrees that she is a dog and that Jesus is the Master. Sounds like the sinner’s prayer to me. Jesus needed her to get to this place before healing could be done because he needed to shock her with his love – to take a journey to a place beyond what she expected. Once she laid herself before the Master, he healed her daughter and in doing so, healed her of her original bondage to law by showing her that he came for all. She came to him as a dog and left him as a child at the table, given way more than crumbs. He changed the rules.

I can imagine how the disciples jaws dropped. This challeneged everything they knew about Messiah. Which I think was the real point. Jesus had only 3 years or so to train (or untrain) these men who would start the church. In this interaction, we see the gospel in full swing. In offering life to this outcast, he showed that it is faith that saves, not works, not affiliation, not heritage.

Cathy Edmonton October 28th, 2012 11:12am

Cathy, that was wonderful. What an excellent insight. I think you have also given us a ‘method’ to interpreting difficult passages – to seek the thread of God’s lavish love in the midst of the tough narrative. Thank you.

TJ India November 18th, 2012 11:35pm