Construction worker becomes radical prophet

What can we plausibly imagine about those gap years in Jesus’s life, some 30 years between his birth and prophetic calling?

The four Evangelists obviously consider those years uninteresting and irrelevant, but our bias for biography pleads for some exploration of the dynamics of his family life and early experience. Personal development is critical for how adulthood eventually plays out, even if it can’t predict particular choices.

Family of origin: Archaeological studies confirm the biblical record that Nazareth was an insignificant hamlet of farming peasants (John 1:46), with a population of perhaps a couple hundred. Its first settlement was sometime around 100 BCE, likely by Judean migrants from Galilee during the rule of the Hasmonean regime (148-63 BCE).

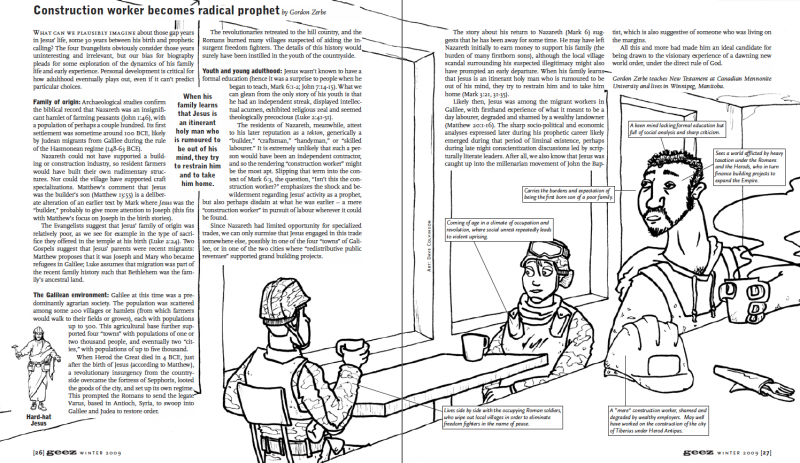

Nazareth could not have supported a building or construction industry, so resident farmers would have built their own rudimentary structures. Nor could the village have supported craft specializations. Matthew’s comment that Jesus was the builder’s son (Matthew 13:55) is a deliberate alteration of an earlier text by Mark where Jesus was the “builder,” probably to give more attention to Joseph (this fits with Matthew’s focus on Joseph in the birth stories).

The Evangelists suggest that Jesus’s family of origin was relatively poor, as we see for example in the type of sacrifice they offered in the temple at his birth (Luke 2:24). Two Gospels suggest that Jesus’s parents were recent migrants: Matthew proposes that it was Joseph and Mary who became refugees in Galilee; Luke assumes that migration was part of the recent family history such that Bethlehem was the family’s ancestral land.

The Galilean environment: Galilee at this time was a predominantly agrarian society. The population was scattered among some 200 villages or hamlets (from which farmers would walk to their fields or groves) each with populations up to 500. This agricultural base further supported four “towns” with populations of one or two thousand people, and eventually two “cities,” with populations of up to five thousand.

When Herod the Great died in 4 BCE, just after the birth of Jesus (according to Matthew), a revolutionary insurgency from the countryside overcame the fortress of Sepphoris, looted the goods of the city, and set up its own regime. This prompted the Romans to send the legate Varus, based in Antioch, Syria, to swoop into Galilee and Judea to restore order.

The revolutionaries retreated to the hill country, and the Romans burned many villages suspected of aiding the insurgent freedom fighters. The details of this history would surely have been instilled in the youth of the countryside.

Youth and young adulthood: Jesus wasn’t known to have a formal education (hence it was a surprise to people when he began to teach, Mark 6:1-2; John 7:14-15). What we can glean from the only story of his youth is that he had an independent streak, displayed intellectual acumen, exhibited religious zeal and seemed theologically precocious (Luke 2:41-51).

The residents of Nazareth, meanwhile, attest to his later reputation as a tekton, generically a “builder,” “craftsman,” “handyman,” or “skilled labourer.” It is extremely unlikely that such a person would have been an independent contractor, and so the rendering “construction worker” might be the most apt in terms of its social connotation. Slipping that term into the context of Mark 6:3, the question, “Isn’t this the construction worker?” emphasizes the shock and bewilderment regarding Jesus’s activity as a prophet, but also perhaps disdain at what he was earlier – a mere “construction worker” in pursuit of labour wherever it could be found.

Since Nazareth had limited opportunity for specialized trades, we can only surmise that Jesus engaged in this trade somewhere else, possibly in one of the four “towns” of Galilee, or in one of the two cities where “redistributive public revenues” supported grand building projects.

The story about his return to Nazareth (Mark 6) suggests that he has been away for some time. He may have left Nazareth initially to earn money to support his family (the burden of many firstborn sons), although the local village scandal surrounding his suspected illegitimacy might also have prompted an early departure. When his family learns that Jesus is an itinerating holy man who is rumoured to be out of his mind, they try to restrain him and to take him home (Mark 3:21, 31-35).

Likely then, Jesus was among the migrant workers in Galilee, with firsthand experience of what it meant to be a day labourer, degraded and shamed by a wealthy landowner (Matthew 20:1-16). The sharp socio-political and economic analyses expressed later during his prophetic career likely emerged during that period of liminal existence, perhaps during late night conscientization discussions led by scripturally literate leaders. After all, we also know that Jesus was caught up into the millenarian movement of John the Baptist, also suggestive of someone who was living on the margins.

All this and more had made him an ideal candidate for being drawn to the visionary experience of a dawning new world order, under the direct rule of God.

Gordon Zerbe teaches New Testament at Canadian Mennonite University and lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.