Bendita Mezcla: Solidarity among Youth throughout NuestrAmérica

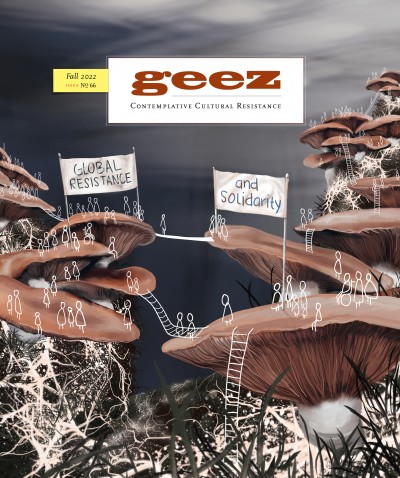

“Caminos de la Bendita Mezcla,” Alexander Serpas, Papel acuarelable/ pintura acrílica, 12 x 18 pulgadas, Febrero 2021.

This interview was originally conducted in Spanish. We include both the English and Español version online.

***

The question of what Bendita Mezcla is can be answered best through metaphor and story:

It’s a pot of stew that’s been simmering over a low heat, and each person who arrives adds an ingredient that they’ve brought from their own culture, from their land, from their hearth . . .

It’s a path, made by walking, traversed in community, from which we emerge transformed by the journey . . .

Once upon a time, there was a meeting beneath a huge mango tree in Paraguay during which a wise community-weaver and a young theologian together planted a small seed that grew and became the largest of all garden plants, with such big branches that the birds of all NuestrAmerica can perch in its shade . . .

So I’ve been told by members of the coordinating team: Fran, Rossy, and Laura. I would have told you that Bendita Mezcla is a formation process for emerging leaders in ecclesial base communities (CEBs) and eco-social movements in what we today call NuestrAmérica. It began with two rounds of mingas – community meetings or mini-retreats based on the methodologies of popular education. These meetings culminated in the publication of a multimedia book of interviews just in time for a continental meeting of CEBs in Guayaquil, Ecuador on the eve of the pandemic in March 2020.

The formation process, the escuelita, began in June of that year out of a desire to share the book with virtual learning communities. Since its inauguration, two groups of young people have completed the first year of the escuelita and some continued on to a second year in 2021. This year, in 2022, an in-person minga is being planned for July in El Salvador, this continent’s holy land.

That’s how I would have explained it, but that doesn’t taste like mango, and Bendita Mezcla does. Instead, I’ll offer my questions – questions that received stories instead of answers.

– Laurel Potter, tutor for Bendita Mezcla, Boston, Massachusetts

***

English Translation

How was Bendita Mezcla born?

Fran: I hold onto the sweet flavour of mangos as the initial flavour, like when you eat fruit before dinner. There is something of this in Bendita Mezcla, of the purest intuition of grassroots faith. What I mean to say is that it was born from the sweet belief that the faith of the majorities will save us. And we have to go back to that every time we feel that it is lacking—in order to refresh ourselves, so that we don’t forget, so that we don’t institutionalize ourselves, so we don’t fight, so we don’t get tired, to heal each other. We always have to come back to that. So with that in our hearts, the idea was born; at that time, it wasn’t even called Bendita Mezcla. It didn’t have a name.

Laura: We met through a screen, that’s it. I remember that I was so impressed by the book that had come out, and I wrote to Fran asking him how to access it so that I could cite it in my thesis. That’s how it started. And some time later, Fran surprised me with a nice message telling me a little about plans for the escuelita and inviting me to be a tutor.

So the escuelita wasn’t part of the original idea, right?

Fran: No. It came about in fidelity to the process. Even within popular education it happens that we perform a sort of intellectual extractivism. We go, we take, and we leave because we got what we needed. With good intentions, yeah? With love, but our commitment was that this process would return to the communities.

We were clear that we were going to systematize, that we would gather in order to learn. Because many grassroots processes stop halfway, because our lives are so chaotic. They don’t get to this step, which is a kind of thanksgiving.

What are the threads that Bendita Mezcla takes up from the great traditions of NuestrAmerica, from our femi-afro-amerindian ancestors? What are the sources or wisdoms that you take up?

Fran: We drink from three Latin American sources. The first is popular education: this absolute confidence in a backwards school with our feet in the air. The second is that we draw on liberation theology, the creation of a theology that belongs to Latin America, going back to listen to poor women and men, and to let ourselves be moved because the Spirit of God speaks there. And the third is recovering a narrative tradition, which has given much fruit in Latin America, and which has to do with an extraordinary capacity to tell what has happened, without making anything up, to give an account of our reality which is heavy with enchantment.

In the world-language of Bendita Mezcla, what does “resistance” mean?

Laura: The story that comes to mind is that of José Morales. In the second year, he was an educator, and he and I led our learning community. We were together, tutoring, and during that time, an armed conflict broke out in his community in Chiapas. They killed people in his community, and his community ended up fractured. It was a conflict of the poor against the poor. And despite everything – it was more than ten kilometres that he had to walk to get to the parish – he continued to walk there to be able to connect to the internet from a community deep in the mountains. His testimony impacted me greatly.

And I always recall the Cuban participants. Because it was much more difficult for them to connect. Fran had to work magic between Jitsi and connecting them to Zoom. But they didn’t give up. Yula still participates today, and she has had such a natural kind of leadership. She has her doctorate in philosophy, and she’s lovely. And she has resisted this difficult piece of exclusion from the digital world, from communication.

Fran: One of the students has said it best. We survived a global pandemic. And we survived by mixing ourselves together, not by isolating ourselves.

That’s been a beautiful gift of these times. To resist the beast – violence, drug trafficking, capitalism, the patriarchy, our own egos, our miseries, hunger – we resist with everyday things. That is, the beasts are huge, and our power is very contextual. I feel that our resistance is hardly ideological, or maybe it’s a different kind of ideological. When we have to struggle against capitalism, we don’t spout a whole speech about why capitalism is bad. Instead, we cook, we pass down recipes from generation to generation. We tell the story of the birth of our communities, and we ask our grandfather or grandmother who founded our community, and we see that there is resistance in this transmission of wisdom. I think that we attack the beasts from below, like we want to eat their feet.

This resistance surprises me and gives me hope. The beast is enormous, and I see that we have small revolutions everywhere, playing out.

Rossy: In 2020, we were still getting used to being virtual. And we are still resisting the exhaustion that virtual work can produce. I mean, since 2020, we’ve been meeting once a week, twice a week. And sometimes, if we have a meeting with our learning community, or if we have to respond to messages, we have to be here with our phones. And I remember in the first year when we started forming the learning communities with Francisco, it was midnight for me and three in the morning for him.

Also, in order to have students from Brazil and the U.S., we had to invent some maneuvers wherein we sent the English speakers with Laurel, and Pedro Pablo speaks Portuguese, so we sent him the students from Brazil. We tried to figure it out and resist everyone who says that diversity is impossible. And we’ve been a really diverse group, in every sense of the word, and it’s worked out for us.

What is solidarity?

Laura: Another story occurs to me. During the first year, I had a student named Cristóbal in my learning community. He’s from Nicaragua. And he had an accident and had to go to the hospital. And we had just started; it was maybe three weeks in. But everyone in our learning community called him and sent him messages. And we passed the news to the whole escuelita, to the large group, and they began to communicate with him. I think it awoke something very beautiful, and very genuine, after such a short time of knowing each other.

I also look at the time that each tutor has given. It’s a tremendous gesture of solidarity, especially these days, when everything has a price, when everything is bought and sold. To do this out of love for the process is so great.

Rossy: Father Pedro used to say that solidarity does not occur by itself, but rather that it is always accompanied by love. And love without solidarity isn’t love. So I believe that the love we’ve put into Bendita Mezcla forms us to be people of solidarity.

Among the group of the students, too, we’ve shown solidarity with all the different developments that we’ve been living through in our different countries. We’ve celebrated wins, and we’ve accompanied each other in different disasters, whether it’s something happening in our country or something personal. I think that we’ve established really strong interpersonal relationships.

And even though our goal is not to form virtual community, and even though people say you can’t form community virtually, I think that our coordinating team has the characteristics of a community. We see each other every week, sometimes so much that we get sick of each other! We have some tension, we argue, we get over it. And these are the characteristics of a community.

Fran: I’m happy that Bendita Mezcla struggles against fundamentalism, even our own, the fundamentalisms of Latin American progressives. We do not believe that north of the border wall there are only enemies. Because we know that folks build resistance everywhere. This is resistance too, yeah? Resisting in a way that maybe doesn’t respect the stereotypes that we are told about who is good and who is bad. It’s not that simple.

Actually, tomorrow marks two years since we inaugurated the escuelita. And that day, they held vigil for George Floyd. I remember that it was striking because we started the school with that image of Trump holding the Bible. Because as Bendita Mezcla, we want to be informed by the Spirit that goes to fight for that text. The stories that are in that book that the beast holds up do not belong to the beast. They belong to Life.

***

Versión en Española

¿Cómo nace Bendita Mezcla?

Fran: Yo tengo el sabor dulce de los mangos como un sabor inicial, como si uno comiera la fruta antes de comer. Hay algo de eso en el origen de Bendita Mezcla, de lo dulce de la intuición más pura de la fe popular. Es decir, nace de la convicción dulce de que la fe de las mayorías nos va a salvar. Y hay que volver allí todas las veces que haga falta – para refrescarnos, para no olvidarnos, para no institucionalizarnos, para no pelearnos, para no cansarnos, para sanarnos. Hay que volver allí. Entonces, con el corazón en eso nace la idea, que no se llamaba Bendita Mezcla, para nada; no tenía nombre.

Laura: Nos conocimos a través de la pantallita, no más. Me acuerdo que me impresionó mucho el libro que sacó, y yo le escribí a Fran, preguntándole cómo conseguirlo para citarlo en mi tesis. Así fue. Y después de un tiempo, Fran me sorprendió con un mensajito contándome un poco en qué consistía la escuelita e invitándome a ser tutora.

Entonces, ¿entiendo que la idea de la escuelita no existió desde el principio?

Fran: No – surgió como fidelidad al proceso. Aun en la educación popular, pasa que hacemos una especie de extractivismo intelectual. Vamos, tomamos, y lo llevamos porque nos sirve. Con buena voluntad, ¿eh? Con amor, pero el compromiso era que esto iba a volver a ellos, a ellas.

Lo que sí estaba claro era, vamos a sistematizar. Vamos a recoger a aprender. Porque muchos procesos populares, por lo caótico de nuestras vidas, se quedan a medias. Y no llegan a este momento, que es una especie de acción de gracias.

¿Cuáles son los hilos que retoma Bendita Mezcla en cuanto a las grandes tradiciones NuestrAmericanas y de nuestres ancestres femi-afro-amerindias? ¿Cuáles son las fuentes o sabidurías que retoma?

Fran: Bebíamos de un triple corriente latinoamericano. El primer es la educación popular, esta confianza absoluta en una escuela al revés, con las patas para arriba. Lo segundo, es que tenía que ver con la teología de la liberación, la creación de una teología propia de América Latina, el volver a escuchar a los y las pobres, y a dejarnos conmover porque el espíritu de Dios habla allí. Y la tercera es recuperar una tradición narrativa, que en América Latina ha dado frutos. Tiene que ver con una capacidad extraordinaria para contar lo que pasa, y no estar inventando, para contar una realidad que está cargada de encanto.

En el mundo-lenguaje de Bendita Mezcla, ¿qué es la resistencia?

Laura: Se me viene la historia del compañero José Morales; en el segundo año, él fue educador. Con José hicimos comunidad de aprendizaje, estuvimos juntos tutoreando, y pasó que estalló un conflicto armado en su comunidad en Chiapas. Mataron a gente en su comunidad, y la comunidad quedó fragmentada. Fue un conflicto de pobres entre pobres. Y a pesar de todo – eran más de diez kilómetros los que tenía que caminar para llegar a la parroquia – él seguía llegando allí para poder conectarse al internet desde una comunidad en lo profundo de la sierra. Su testimonio a mí me impactó mucho.

Y siempre me acuerdo de las compañeras cubanas. Porque era mucho más difícil conectarse. Fran tenía que hacer magia allí con Jitsi, para conectarla a Zoom, pero ellas no se rendían. Incluso Yula está hasta hoy. Y ha tenido una sencillez para estar al frente de todo. Siendo doctora en filosofía, y es un encanto. Y ha resistido lo duro de la exclusión del mundo digital, de las comunicaciones.

Fran: Lo decía uno de los chicos con más claridad, sobrevivimos a una pandemia mundial. Y también sobrevivíamos mezclándonos, no aislándonos.

Y hay un regalo hermoso de estos tiempos. Y es a resistir a la bestia – la violencia, el narcotráfico, el capitalismo, el patriarcado, nuestros egoísmos, nuestras miserias, al hambre – con cosas muy cotidianas. Es decir, grandes bestias y potencias muy del contexto. Siento que nuestra resistencia es poca ideológica, o ideológica de forma distinta. Cuando tenemos que luchar contra el capitalismo, no hacemos un discurso de por qué el capitalismo está malo, sino que cocinamos, nos pasamos recetas de generación en generación. Contamos el nacimiento de nuestra comunidad, y preguntamos al abuelo, a la abuelita que inició la comunidad, y vemos que en esta transmisión de sabiduría hay resistencia. Creo que atacamos a la bestia por abajo, como que le queremos comer los pies.

Esta resistencia me sorprende y me da esperanza. La bestia es enorme y veo que tenemos pequeñas revoluciones allí, sucediendo.

Rossy: En el 2020, estábamos acostumbrándonos a la virtualidad. Y al cansancio que puede producir la virtualidad estamos resistiendo también. Por ejemplo, nos vemos, desde el 2020, una vez a la semana, dos veces a la semana. Y a veces si hay reunión de comunidad de aprendizaje, o de estar contestado mensajes, es de estar aquí, con el teléfono. Y me acuerdo que en el primer año, cuando empezamos a formar las comunidades de aprendizaje con Francisco, para mí eran las doce de la noche. Y para él, eran las tres de la mañana.

También hemos resistido eso, que para tener a estudiantes de Brasil y de Estados Unidos, hicimos una maniobra de que a Laurel le mandábamos los que hablaban inglés, y a Pedro Pablo que habla portugués le mandábamos a los de Brasil. Tratábamos de hacer esta maniobra y resistir a eso que dicen que no se puede tener diversidad. Y hemos tenido una gran diversidad en todos los sentidos, y ha ido caminando.

¿Qué es la solidaridad?

Laura: Se me viene otra historia. En el primero año, yo en mi comunidad de aprendizaje tuve a Cristóbal, que es de Nicaragua. Y tuvo un accidente, y cayo al hospital. Y teníamos muy poquito, como tres semanas que nos habíamos configurado. Pero toda la comunidad le llamaron, le mandaron mensajitos. Después pasamos el dato a la escuela, a todo el grupo, se empezaron a comunicar con él. Se despertó algo muy lindo, muy genuino, a poco tiempo de conocernos.

También veo el tiempo de lxs voluntarixs que han sido tutores o educadores. Esto es un gesto de solidaridad tremendo, sobre todo ahora cuando todo se cobra, cuando todo es rentable. Hacer esto por puro amor al arte y amor a la escuela me parece genial.

Rossy: Padre Pedro decía que la solidaridad no se da por sí sola, sino que va acompañado con el amor. Y el amor sin solidaridad no es amor. Entonces yo creo que el amor que hemos puesto a Bendita Mezcla nos hace ser solidarios.

Dentro de los grupos con lxs escuelerxs, también, hemos sido solidarios en todos los procesos que van viviendo los países. Hemos celebrado los triunfos, hemos acompañado los desastres, ya sea de un acontecimiento del país o de manera personal. Creo que hemos establecido relaciones interpersonales bastante buenas.

Y aunque el objetivo no es formar comunidad en la virtualidad, y aunque muchas personas piensan que no se pueden formar comunidad en la virtualidad, yo creo que el equipo coordinador tiene las características de una comunidad. Nos vemos semanalmente, ¡a veces hasta nos aburrimos de vernos a cada rato! Tenemos estas tensiones, de discutir, de resolver. Y estas son las características de una comunidad.

Fran: Me alegra que Bendita Mezcla lucha en contra de los fundamentalismos, aún contra los propios, del progresismo latinoamericano. No creemos que del muro para arriba hay sólo enemigos. Porque sabemos que los pueblos construyen resistencias en todos lados. Eso también es resistir, ¿no? Resistir de una manera que quizás no respeta a los estereotipos de cómo nos dicen que hay que hacerlo, de quienes son los buenos y quienes son los malos. No es tan sencillo.

Efectivamente, mañana son dos años que inauguramos la escuelita. Y ese día velaban a George Floyd. Me acuerdo que fue impresionante porque empezamos la escuela con esa imagen de Trump sosteniendo una Biblia. Porque Bendita Mezcla quería estar marcado por el espíritu de ir a disputar estas letras. Las historias que hay adentro de ese libro que la bestia levanta, no son de la bestia. Son palabras de vida.

_Rossy Iraheta Marinero, Laura Lienlaf, and Francisco Bosch serve on the coordinating team for Bendita Mezcla. _

Rossy forms part of the CEBs of the Bajo Lempa region of the National Network of CEBs in El Salvador and serves on the core team of CEBs Continental. Psychologist by profession and popular educator by conviction, she is the Education Coordinator for FUNDAHMER, a Salvadoran nonprofit.

Laura is a theologian who accompanies collectives of family members that search for their disappeared loves ones in Mexico. She forms part of the coordinating team for the CEBs’ Óscar Arnulfo Romero school.

Francisco is an Argentine theologian. He has published two systematic books of popular and narrative theology: El grito descolonizador and Bendita Mezcla. He lives in Mar del Plata and works in the field of education.

Laurel Marshall Potter is a North American theologian who works among the CEBs in El Salvador.

Start the Discussion