Basic Income: The Price of Human Dignity

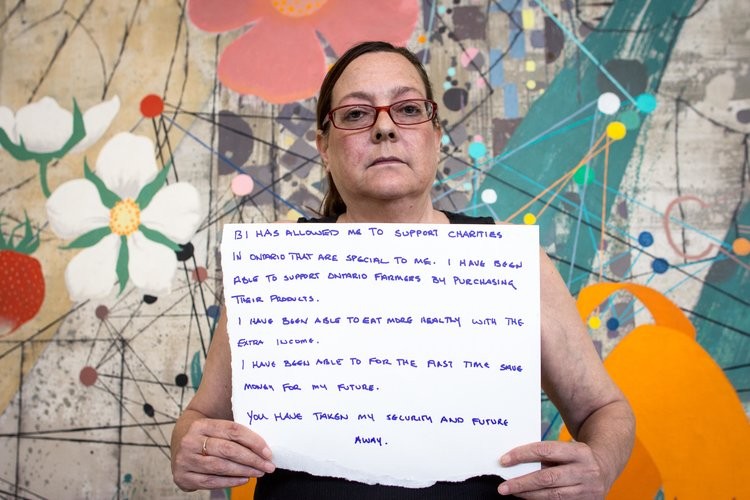

Hamilton, Ontario (from photo series Humans of Basic Income) Credit: Jessie Golem (link below)

It’s 6:30 on a drizzly November morning on Main Street in Winnipeg. Jessie, coffee in hand, is scanning through her agenda on her way to work.

She shifts her gym bag to the other shoulder as the elevator rises to the 29th floor, and wonders whether her mother can pick up the kids and give them dinner this evening. That would give her a bit of extra time to work on the new contract she just picked up. Jessie sighs and books a fitness class for noon before she dashes off to her first meeting of the day.

Just down the street, the doors at Siloam Mission open to admit the 60 or so people waiting for breakfast. Brenda waits patiently for coffee and a pastry, and asks whether a doctor might be in later to give her something for her debilitating cough. Last year, she spent several weeks in the hospital recovering from pneumonia.

Brenda isn’t homeless; she lives in a tiny room in a downtown residential hotel where her rent is paid directly by the province, leaving her just over $300 a month for basic needs. She has no cooking facilities and shares the shower (when it works) with several other tenants. She doesn’t feel safe in her room and spends as little time there as possible. She wears most of her clothing all the time so it will not be stolen.

After breakfast, Brenda will walk to Winnipeg Harvest food bank, where she sorts potatoes. She is a regular, and, while she keeps mostly to herself, she enjoys being around other people. Brenda has challenges in her life and sometimes stays away for days or weeks at a time, but most of the people at Harvest seem glad to see her when she comes back.

Both Brenda and Jessie have too much and too little. Brenda has too much time–more time than she needs or wants–to wait in lines for services, to walk for miles every day and to think about the bad breaks and bad decisions that have brought her here. It’s hard not to be drawn back into bad habits, which is why she likes to spend time working at Harvest.

Jessie has no time that isn’t allocated to her job, her kids, her home, and the thousand necessary requirements of a busy life. Jessie has money–not a lot, but right now she has enough to stop by Starbucks every morning and to ensure that her kids have access to decent daycare. However, this income isn’t secure. Like many people her age, she works on a contract basis. Today, her rent is paid and she has money to spend, but there are no benefits and no guarantee that this contract will be renewed at the end of the year. She seems to be either running flat out taking on as much work as she can to save for the lean times, or languishing between contracts, trying to get more work. She can’t help but wonder whether life is meant to be lived without a spare moment to think or to share a cup of tea with a friend.

Both Jessie and Brenda could benefit from a Basic Income. Basic Income has received a lot of attention worldwide, but most of us know little about what it means–whether it is feasible and what impact it could have on our lives. Ontario recently introduced a bold experiment designed to see if offering a Basic Income would give people the resources they need to break free of poverty and build better lives. Before anyone could know whether it would work, the experiment was cancelled after a provincial election.

In the Ontario experiment, someone like Brenda, with no money from other sources, would receive almost $17,000 a year–more than twice what she currently receives in basic living expenses and rent. That money would allow her to rent a safer apartment with her own bathroom and kitchen. She could buy a couple of cans of beans or chili rather than relying on Siloam for meals, and she would have a home where she could spend time alone or with a friend. Instead of drifting from crisis to crisis, she would have the modest luxury of deciding how to spend her own money and what to do with her time. Perhaps she could visit the small community where her brother lives. An income of $17,000 can buy dignity. Self-respect can provide a platform on which to create a more stable life.

Jessie too would benefit from Basic Income. In the Ontario experiment, her Basic Income would decline by 50 cents for every dollar she earned, so that she would receive nothing at all if she earned more than $34,000 a year. However, Jessie’s income is insecure. Today she might earn too much to receive a Basic Income, but in six months’ time, she might be unemployed. If her job ends tomorrow, Basic Income would be there to fill the gap between contracts. More importantly, she wouldn’t have to struggle so hard to find additional contracts and work extra hours whenever they come along, because a Basic Income would be there when she needs it.

Canadians can afford a program that guarantees no one will ever live on less than $17,000 a year. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, if the Ontario program were offered to all Canadians, the cost would be $43 billion a year. However, we already spend $20 billion a year on the provincial social assistance programs that a Basic Income would replace. Therefore, the net cost of a Basic Income program in Canada would be $23 billion a year–almost exactly what we now pay for our Canada Child Benefit and about half of what we pay for seniors’ pensions. We can afford this program–if we want it.

Basic Income fills the gaps in our social safety net, offering income security to everyone from laid- off factory workers to white-collar workers losing jobs to automation and artificial intelligence. If we address poverty and income insecurity by giving people the resources they need to live their lives with dignity and respect, we no longer have to treat the consequences of poverty when people like Brenda are hospitalized because they don’t have safe housing, warm clothes, and good food to fill their bellies. Basic Income is not a cost, but rather an investment in the kind of society we want to have.

Basic Income also has other consequences in our work-obsessed society. Many of us look to our jobs to find meaning in our lives, and we treat frenzied lifestyles as a mark of virtue. This causes distress among those who can’t find jobs they value. It also undervalues the importance of creative work, care work, community building, and fills time to think, reflect and dream. Basic Income redistributes income, but it also redistributes time. It challenges us to think about what we need and what we value, and reminds each one of us that everyone we meet is more than the job they are paid to do.

Evelyn L. Forget is an economist and the author of Basic Income for Canadians: The Key to a Healthier, Happier, More Secure Life for All. She lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba. One of her earliest experiences with redistribution took place the year she turned 12 and her father died. She spent a lot of time that fall working with a church youth group to create Christmas hampers for “the needy,” only to have one of those boxes delivered to her own home. It was a vivid lesson against “othering.”

Image: Jessie Golem

Dear reader, we welcome your response to this article or anything else you read in Geez magazine. Write to the Editor, Geez Magazine, 400 Edmonton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2M2. Alternately, you can connect with us via social media through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Start the Discussion