Tree Medicine

Erin Cutler , “Under you spreads a root system as immense as the branches you see above ground,” iv from “Instructions on Being with Trees,” 2020.

Trees have been my friends for as long as I can remember.

They are stoic in their wisdom and presence, never imposing but quietly connected just the same. One only has to consider the mighty cottonwood or the healing of cedar or tamarack to begin the ascent that is tree worship.

My apprenticeship with trees began when I was barely four years old and I planted a stick in the ground in our urban East End neighbourhood of Ottawa, Ontario. By the time we prepared to leave to return to our northern Ontario community four years later, the stick had grown into a tree that shaded the front of our townhouse. I found myself grief-stricken, crying fat tears at the knowledge that this was goodbye.

In those early days, I attended Catholic school where I learned of blessings, miracles, saints, and sinners. Though I eagerly committed to my Confirmation and beamed at the oratory responsibilities bestowed upon me by my teachers and priest for my First Communion, it was my time with trees that truly nurtured my reverence of ceremony and ritual.

As an Algonquin member of the Pikwakanagan First Nation, I have struggled over the years, like many others affected by historical oppression, to find a sense of my own identity and spirituality. A white-coded Anishinaabekwe, there were many situations where I struggled to find a way to belong. Many Indigenous people can speak to this reality of having one foot in both worlds – the mainstream and Indigenous worlds, as they exist now. History and harm separating me from my community by shades of colour depicted in melatonin.

It was our return to the north that left me grasping, without connection to the spirituality that I had become acclimated to during my time in Catholic school. The community was simply too small to support institutions; my elementary school consisted of thirty people, from junior kindergarten to grade eight, including teaching, administrative, and janitorial staff. The town had one paved road and many, many trees.

Though our community was small, our connection to family deepened. My maternal grandparents and uncle lived few doors away, their home situated on a knoll leading toward a deep blue lake that was encircled with evergreens and famous for its dangerous drop off and tales of monstrous fish. I can still remember the first time my grandfather gave in and allowed me to take the peddle boat out on my own with my sister. I copied my uncle and sketched in my sketchpad as we peddled and cruised.

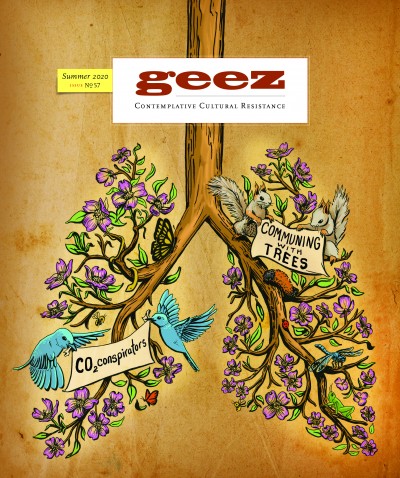

Hours were spent floating and sketching the wondrous stands of the pointy topped soldiers that guarded the shores of Caramat Lake and reassured me as we peddled close to shore. The small town was an isolating place to live, but while I played pretend games in the coolness of the forest floor, the strength of the trees sheltered me as I grew. I began to craft offerings of prayer and thanks, my hand tenderly placed upon the rough bark of thick and spindly trunks alike. Without communion or candles to light, I noticed the roots and the relationships at play amongst the trees.

As an adult, I continue to nurture the heartwork I discovered as a child, ever an apprentice to the trees. I am a member of the bear clan. It is a tradition for the bear clan members to hold gifts as a plant medicine woman, or mashkikiikwe, in order to offer healing gifts to the people, or Anishinaabeg.

Emboldened by written works of Robin Wall Kimmermer, I am still working to gain and share the knowledge and wisdom of trees, for it is without limits and so very similar to the teachings and values of my spirit. The rustling lullaby of wind in leaves, the rhythmic offerings of fruits, nuts, sap, and bark – all of it invites us to be kind to each other through their examples of generosity, giving without asking, and regularly falling to sacrifice themselves for our warmth and care.

There is a gift in being called on to help others remember the spirit of trees. Trees can create safety, as humble as their offerings may be, by simply remaining rooted and providing shade for the weary soul. When I find myself called on to offer spiritual counsel to my community, it is in the form of doula care. As a doula I facilitate teachings of birth and death, close to the practices once inherent in the upbringing of our communities.

I am regularly stricken by the teachings of cedar, a medicine tree gifted to the Anishinaabeg that offers grounding and protection as we enter and depart this place for the spirit realm. It is astonishing, the sheer endlessness of gifts offered by the cedar tree.

These teachings continue to form and reform, time and again. The strength of the golden tamarack parent towering at the edge of the road, grasping through the dirt to keep roots anchored to rock deeply set below the road. Across the concrete, the baby tamaracks flourish under their parent’s watchful position. All at once I am certain of the better life it has secured for its offspring: a life of unencumbered growth and better soil. These kin have been released to grow, free from the inevitable pressures applied by gravity and the elements withstood by the towering parent on the other side.

The selflessness of trees continues to resonate deeply within me. My understanding of my own family’s story of resilience has similar heroic underpinnings and I continue to look deeper at what the trees wish to teach me.

Tree medicines are plentiful yet somehow easily overlooked. We cannot continue our treading upon this world without learning from the gallantry of trees. I will continue to give thanks to the Creator for the offerings of medicines, of teachings that hold me up to withstand hardships brought down by pain and suffering, greed and mistrust. I will continue to hold space for others to respect the wisdom that has been gifted to us and forgotten, gently urging the remembering along.

Chrystal Wàban is a wife, mother, Spiritual Advisor/Founder of Blackbird Medicines and Indigenous Rights Program Coordinator for KAIROS Canada.

Start the Discussion