The Tree that Fell in the Forest . . .

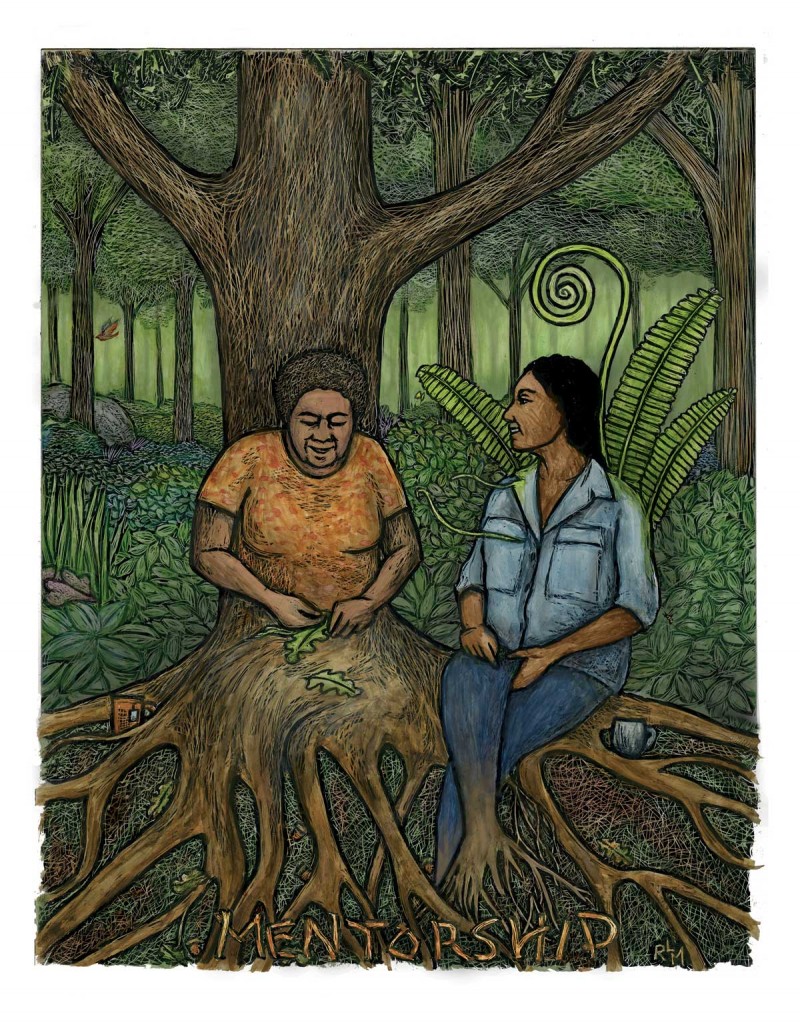

Ricardo Levins Morales , “Mentorship,” 2019, ink and watercolour on claybord 11 x 15 inches.

“My soul would sing of metamorphoses . . . of these bodies becoming other bodies . . . ”

– Ovid, The Metamorphoses

In coastal North Carolina, the ocean laps at the trunks of bald cypress, or what were bald cypress. What remains of bald cypress swamps are snags of dead trees, freckling the landscape. Along this coast, seas are rising at some of the fastest rates in the United States, bringing with them salty water that is deadly to the freshwater-adapted cypress. As the saltwater seeps in through manmade irrigation canals, the salt intrudes miles inland, decimating tracts of coastal forest and leaving spears of dead trunks skewering the beaches.

On the opposite coast, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, a 5-millimetre-long native beetle is wreaking havoc on the stunning ponderosa pine. Under normal conditions, the mountain pine beetle is an important part of the ecology, culling older trees whose time has come to give itself to the forest floor. But we’re not under normal conditions. A mixture of unprecedented drought, decades of fire suppression, and climate change have resulted in the proliferation of the beetles. So rather than a force preserving ecosystem balance, they have become destroyers of forests, leaving behind rows of rampikes as monuments to the ecological crisis.

The world is pockmarked with similar stories: Sitka spruce in Oregon, olive groves in Italy, and ash trees in Denmark. These cathedrals of dead trees are called ghost forests. It is a name whose uncanniness goes beyond the haunting physical remnants of the once-living pines, tupelo, and cypress. What also remains is their spirit. I don’t mean spirit in the body-soul dualism that has come to dominate Western Christianity. I mean spirit as the essence of life that permeates their material bodies, bound up in carbohydrates; sorbitol and sucrose, glucose and fructose. These carbon-based sugars are the spirit of life in forests, feeding, as they do in our own bodies, sustenance and growth.

Trees, even dead ones, have a story to tell. When a tree dies, this sugary spirit decomposes into the ground, feeding the next generation of life that is to grow in the space where the trees once dominated. Their song plays on, dissolved and metamorphosed into other bodies. These trees, sapped of their life, are emblems of our Anthropocene moment: a knife’s-edge between life as it was and the transformation into something else. A moment that looks so much like death, but in the eyes of the wise soil, is the making of something fresh and beautiful.

As distorted systems are warming our world and decimating what we love and cherish, ghost forests might offer us wisdom. While living, a tree does all it can to defend itself: calls on symbiotic insects, heals itself using sap, and cooperates with its neighbours to share energy. In the face of climate crisis, we ought to fight like hell for what is left. And yet, that fight may not be enough. Inevitably, from infection or from old age, the tree will die. In its death, it prepares the world around it for regeneration, sending its energy back into the ecosystem. The tree offers itself as a nurse log, a nursery for the cultivation of the next generation of fungus, mosses, ferns, and pines. What happens when our efforts to stop climate change are not enough? Like the tree, our world may come crashing down, but like any ecosystem, something new and young is there to take its place.

For what will we be a nurse log?

Avery Lamb is a student, scholar, and activist studying the intersection of Christianity and the environment at Duke Divinity School and the Nicholas School of the Environment.

Start the Discussion