The Dance with Our DNA

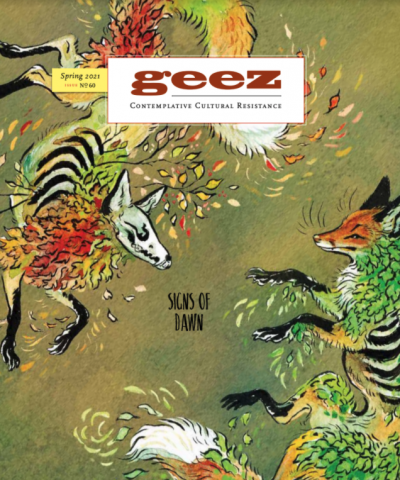

Image credit: Angelica Frausto, “My Ancestors Hold Me”, 2020, digital, 13 in x 13 in.

As a mixed person with Indigenous, Latinx, and white heritage, I’ve become practised at acknowledging the historical complexities that live within my own body.

The audio is a transcript of the written piece recorded by Naomi Ortiz for Geez Out Loud.

I came to doing ancestral work not because I had access to information through websites or even family stories, but because I felt responsibility to legacies that live on in my body. I am aware that violence got me here as much as love. Ancestral work is an invitation to the in-between.

Sitting on the side of the road at the edge of the desert, I look up into a mountain ridge full of Palo Verdes, Ocotillos, Jojoba bushes, and Saguaros. Intuitively, I know if I could see my ancestors and their numbers, they would stretch like this desert plant life as far as I could see.

I have had to make peace with where I’ve come from to understand my lived experience in the day-to-day world. Undocumented migration, forced displacement from ancestral lands, and colonizing history have all been passed down in one way or another, ending up in me. Before I could engage politically, I needed to find comfort with who I was and understand my responsibility to the world. My living family members to some extent or another all dance in confusion or shame with their DNA. I wasn’t going to receive this knowing from them, but perhaps through my own exploration I could offer mending to us.

Ancestral work is mending work. Although this work is often perceived to be healing with an assumption of restoration, I find it much more in line with how my friend describes mending cloth. She describes that in order to mend a knitted piece, she must unravel it further, pulling it apart until she has solid strings to work with. Then she can begin to mend. When she’s done, it might be hard to see the mended section; the yarn may feel rough where the rest of the garment is smooth and soft. The mended section may look slightly lighter or darker. Mending changes the entire piece of clothing forever.

Healing is often used to justify the prevention and eradication of my disabled body. Healing, in the sense of restoration, is a focus on the future; it can be compelling because it releases us from here and now. Mending asks us to lean into the vulnerability that this moment offers and to accept that change has occurred. What continues into the future will look different than what existed in the past.

I do this through deep meditation. Ancestral knowledge that lives within my body isn’t delivered to me through words or stories. It exists like a taste in the back of my mouth or a shape I can’t quite make out in the distance. I try to listen to and take in this fuzzy information. I know strength lies there, as does violence. As I move through my days, work, and relationships, I have the choice to do better, or at least to do different. I hope that the choices I make in support of the Indigenous communities on whose land I live, and the choices I make in poetry and art exploring my grief about climate change, carry ripples of solidarity and integrity. Yet, I don’t know. I will have no way to know – and that’s part of the ancestral legacy that only the next generation will be able to judge.

Ancestral work is witnessing work. I don’t have access to historical documents detailing the brutality that I’m sure exists in my lineage, but I feel it in my body. Like picking up a trace of smoke in the wind, I feel it on a subtle level. I acknowledge and grieve both the harm perpetrated by my ancestors, and my ancestors’ experience of annihilation that leaves a lingering ache. The bravery of those ancestors who made choices to do the right thing feeds my courage and is something I celebrate.

Acknowledging my ancestors as individuals is different than how I relate to them in my spiritual life. My ancestors have become witnesses to my life. This collective power is what I’ve clung to when I have felt all alone. I choose to resurrect a faith in the ancestors who show up to support me and my highest good. I lean back into their stewardship. I trust what I can never know. I also believe that the ramifications of how I live my life affects not just future generations, but reverberates backwards to mend. Not as a way to absolve, but as an opportunity to be more in alignment with the truth. To be in touch with understanding that much of the violence of today is built upon ancestral actions. I do not turn away or distract myself from things that are hard. Yet I also do not submerge myself below the depths of that which inspires intense grief.

Ancestral work is grief work. I found that I have to make ritual space for it. What that looks like for me is simple. Most mornings I attend to my grief and shine a light on what is existing in that tender spot. I tell my ancestors what I’m grieving. I ask them to witness me. Tending to my grief this way doesn’t offer resolution, but it does allow me an attention to tough things in a measured but real way. I also create art to delve deeper into my own understanding of what I’m actually feeling.

Crip ancestors also have a lot to teach me. I’ve learned about ingenuity, activism, defined limits, and necessary boundaries from previous histories of disabled elders. However, I’ve also observed what internalized shame around disability looks like.

I asked myself, what do these ancestors teach about power and privilege? What about survival and choice? Resurrecting their stories through a critical lens as well as spotlight of hope helps me to do my own work with the learned desire for supremacy.

Sometimes I find myself wondering if ancestral work borders on religious faith. I don’t know if I have absolute trust in the ways that I feel guided by ancestors. I try to taper intuitive knowledge with my own common sense and values of what is wrong and right. But I also don’t know if I have absolute trust in religious saviours or figures either. Mostly, I think what I experience is gratitude.

Ancestors as people are different than ancestors as energy. I learn how to be comfortable doing the deep work, relying on and creating rituals around that which I may never clearly understand. What I do trust is the process. By committing myself to deepen, mend, and listen, I am hopefully engaging in my own growth and enhancing the ways I show up and am responsible to the world.

Naomi Ortiz is the author of Sustaining Spirit: Self-Care for Social Justice and lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Start the Discussion