Building a Tomb: Dispatch from a Compost Chaplain

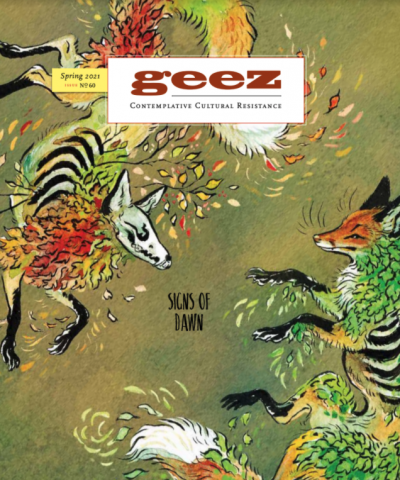

Image credit: Compost artists Mindful Waste, Lilly Lawrence, Yehuda Arye Potaznik, Jerry Ingeman, Em Jacoby, and LiAnn Grahm.

The stench of death is nearly impossible to contain when organic matter is left to decompose in the open air.

The audio is a transcript of the written piece recorded by Justin Eisinga for Geez Out Loud.

The stench of death is nearly impossible to contain when organic matter is left to decompose in the open air. If you live on or near a farm, this principle is one you encounter on a regular basis. But you do not need to be a farmer to understand that the scent of decomposition means something altogether wonderful is occurring. The smell of rotting food is a sign of life, indicating that intricate processes involving bacteria and fungi are at work. For people who compost, it is also an emblem of future food on the table – for the result of these processes contributes to the health of the soil in our gardens.

Compost, at its core, resembles a Shakespearean tragedy, as two lovers find themselves intertwined at their death. To generate healthy compost, two elements are required: carbon and nitrogen. We contribute these elements to our compost piles when we dump our green waste (in the form of food scraps and plants) and introduce it to our brown waste (dead leaves or straw). In their last days, the disintegration of these two types of matter introduces these foundational elements into the intricate dance of death and decay.

This dance is not only at the heart of composting; it is essential to all of life. “In nature, death and decay are as necessary – are, one may almost say, as lively – as life, and so nothing is wasted,” says Wendell Berry. To build a compost bin is akin to building a tomb, except this tomb is not meant to encase death permanently. The compost bin is a tomb built for resurrection.

***

I found solace and solidarity while building a tomb. During a season of great frustration and turmoil caused by the loss of social interaction and regular community rhythms, I dug holes with students, faculty, and staff at Canadian Mennonite University in the autumn of 2020, while we laughed and lamented about the state of academic learning and the world at large. Loss was ever-present with us in the transition to online learning and the closure of Outtatown Discipleship School, a gap-year program that had a profound impact on the lives of many students past and present. Together we needed to build a tomb. We needed to build a site of resurrection, an ossuary intended for the abundance of life through the death of matter.

Standing in the legacy of many who had advocated and yearned before me, I was hired by the university to research, design, and implement an on-campus composting system. I spent the summer learning all about manure and various methods for disposing of food waste on a campus of our size. I looked at all sorts of building designs and mechanical systems. At one point we were even thinking of converting an old shipping container into a composting facility. In the end, we settled on a simple three-bin system located behind our on-campus farm.

Alongside a newfound community of unexpected allies from various departments of the university, we organized a week of construction with students, faculty, and staff. Volunteers cleared the area, dug holes for posts, and screwed on planks of untreated lumber. Together we laboured and told stories; we were painfully honest in our conversations about the difficulties of the year while building something hopeful at the same time. One student, frustrated with how overwhelming everything was feeling, jammed her shovel into the ground, experiencing a visceral feeling of release as the dirt slid off into a pile of soil.

***

Building tombs is difficult work. It requires the gathering of many resources, including a community of workers and a pile of supplies. An eye for design and the rallying cry of a project manager are crucial components of the tomb-building experience. In my work, I have come to learn that building a place for things to die is ultimately an endeavour of building a community.

I wonder if this is what it was like as the wounded body of Jesus Christ hung from a Roman torture device. While Jesus was up there on the cross, I imagine a flurry of activity as his family, friends, and followers recognized that His death was imminent. I envision Mary Magdalene organizing everything, Joseph of Arimathea gathering the appropriate supplies, and the apostle John comforting everyone in their confusion and sorrow. They were to prepare a tomb, but unlike those of us who compost, they had no idea that this tomb was being built for resurrection. Unbeknownst to them, they were entering a liminal space marked by the feeling of loss and the expression of grief; the sealing of the tomb was to be a definitive indicator of the finality of death.

This liminal space is exactly where I find myself, now that the tomb is built and the rot has begun. “It takes willingness, fortitude, knowledge, skill, and a deep trust in Spirit,” says hospital chaplain and spiritual companion LaVera Crawley, “to go into these dark places as both witness and companion.” I have begun thinking of myself as a sort of “compost chaplain.” It has become my task to speak about matters of life and death with students, faculty, and staff, while attending to the death of matter in the compost bins behind the farm.

***

One way in which we must mark the liminal spaces of our lives, including the compost pile, is through ceremony and ritual. At the end of her book about Indigenous wisdom and plant science, botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer tells a story about minidewak, the Potawatomi giveaway ceremony. “Our elders say that ceremony is the way we can remember to remember,” says Kimmerer. “In the dance of the giveaway, remember that the Earth is a gift that we must pass on, just as it came to us.”

As I write this, winter has taken its strong and lengthy grip on Winnipeg, and the excitement of composting has faded. The tomb has been built and the smell of rotting food is replaced by the sting of icy cold air passing through my nostrils. In this liminal space, I am curious about the rituals that took place amongst Jesus’ community after they laid him in his tomb. I am curious about the ancient ceremonies performed by Indigenous peoples used to prepare loved ones for burial, even when the ground was icy and firm. I also wonder about the importance of ritual and ceremony as we build our own tombs for resurrection. For now, I offer this prayer every time I empty a container of nitrogenic food waste into its grave, laying it to rest with a comforting sheet of dead leaves that will become its carbon-rich companion:

Creator of all that lives, moves, and has its being

Attend to the death of this matter

As we attend to matters of life and death

In our lives and in the life of the Earth.

Amen

Justin Eisinga is chaplain of the compost and student of theology at Canadian Mennonite University in Treaty 1 Territory, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Start the Discussion