Reading the Torah Towards Liberation

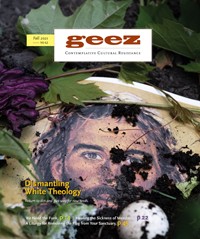

Melad Jajou, “The Re-Creation of Adam,” July 2021, Gouache and Prismacolour on Mylar, 13.25 x 7.5 inches.

Twice a week, my chevruta (learning partner) and I, both of us Black, Trans Jews, spend a few hours working our way through a page of Talmud, word by word.

Between the dictionaries and notebooks stacked up beside us, we catch a glimpse of the future, a shared vision in which we, and our people, are free.

Talmud plays a central role in my life, and the chevruta relationship is vital to studying as a practice. We learn from each other, witness each other’s brilliance, hold each other accountable, and offer each other a soft place to land when the text (and the world it represents) hurts. Together we can reach backwards into our tradition to find tools and strategies, and practice the love and care it takes to move us towards a world liberated from anti-Blackness and transphobia. We know that when we bring ourselves to meet each other and the rabbis in any given text, we aren’t passively receiving a set of laws; far from it. We receive the offerings of our ancestors and offer parts of ourselves in turn, and we are both changed because of it.

Recently, my chevruta and I studied the text that introduces the concept of pikuach nefesh (Talmud Bavli Yoma 83a, 85a/b). Pikuach nefesh grants permission to suspend halacha, Jewish law, when a life is in danger. Often translated as, “to save a life,” its literal meaning is closer to, “to open up a soul.”

In this text, the rabbis present a dilemma: you pass a pile of rubble on shabbat and you suspect that someone is buried underneath. The actions it would take to uncover them, however, are not permitted on shabbat. Immediately they respond that, because of pikuach nefesh, you dig them out. Their clarity is striking. Their students ask for proof. Whether it’s ignorance or due diligence that leads them to question their teachers, or some combination of the two, what follows is a process that allows for a radical shift in what’s considered normative.

The rabbis are operating on a key assumption: life supersedes practice. To be clear, this is not to say that life supersedes halacha. In fact, they insist that life is fundamental to halacha. As we sat in front of the text we found ourselves in the company of thinkers who would take our questions seriously, something we are rarely afforded in contemporary Jewish spaces. What would it take for the divinity of Black people to be accepted as truth? How do we get to the point where Black Lives Matter is redundant as a political slogan because it’s made manifest in systems of care, in respect for our shared humanity, and in our ability to thrive? These questions, for us, are not abstract. As in the case of the person buried under rubble, it is life and death, and we see daily the ways in which people choose their comfort over our lives.

I know that my life – my thoughts, relationships, desires, way of moving through the world – and those of my chevruta, are holy. It’s not ego that leads me to this conclusion, but humility before the One/ones who made me. Personally, I don’t need this knowing to be grounded in Torah. It is a fact of my life and I trust it comes from a divine Source. But for those who do need to see it plainly, it’s been there all along.

The Torah says, “Observe Shabbat.”

The rabbis say, “People are dying.”

G!d affirms us in what we already know. G!d says, “Live.”

Kendra Watkins lives, works, and listens in Detroit, Michigan (Waawiiyaatanong), where they seek to bring liberatory Jewish practice to marginalized Jews.

Start the Discussion