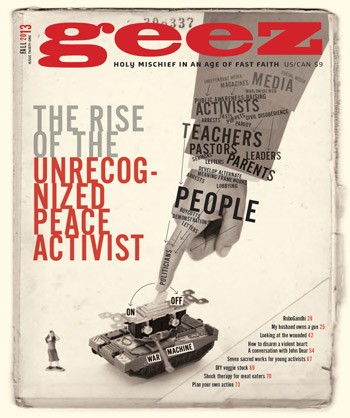

How to disarm a violent heart

Martin Sheen and John Dear Credit: Øyvind Bjørgo, http://www.flickr.com/photos/oyvindbjorgo/8543869187/

A conversation with John Dear on the inner life of an activist.

John Dear is an American Jesuit priest and peace activist who has been arrested more than 75 times for acts of civil disobedience, protesting war, nuclear weapons and injustice.

Dear turns his trials into stages for national conversations on the ethics of nuclear weapons and drone warfare. On April 9, 2009 he was arrested with 13 other anti-war activists for trespassing on the Creech Air Force base in Nevada to protest the Obama administration’s drone attacks in Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan. At the trial in September 2010, three expert witnesses spoke for hours about civilians killed by American drones, about citizens’ duty to stop war crimes and about the necessity of breaking minor laws in obedience to a higher law.

Astonishingly, the judge asked for three months to think it over. The judge ultimately found Dear and his fellow protesters guilty but gave them time served instead of jail sentences. Dear has been influenced by the lives and teachings of other nonviolent activists: Jesus, Gandhi, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr. and also Daniel and Philip Berrigan, with whom he has worked. He has written 24 books and delivered thousands of lectures and workshops on nonviolence, disarmament and spirituality.

Josiah Neufeld interviewed John Dear by phone and email at his home in Cerrillos, New Mexico in March 2011 and May 2013.

Tell me about the inner life of an activist.

If you’re going to be standing up against big, horrible injustices – I’m looking at Los Alamos where they’re building a new-generation nuclear weapon, the bombings in Afghanistan, the U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan – you have to be doing your inner work. Once you start scratching the surface of the powers of death and violence, it can trigger your own past wounds and stir up the violence within you. You think you’re working to get rid of nuclear weapons, but really you’re mad at your mother. Very few activists work on this. Millions of activists who worked against the Vietnam War in the 1960s were really angry and got burned out. But that’s not what happened with Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day or Daniel Berrigan.

How did the greatest peacemakers do it? They took quality time in prayer or meditation every day. The reason we don’t do that is that when you sit down to meditate you have to face yourself and all the violence inside you. If you’re going to give your life for a new world of peace you have to let go of your anger, bitterness, resentment. All the religious traditions teach that – allowing your heart to be disarmed and allowing the springs of peace to bubble up within you so you can radiate personally the peace you seek politically.

How did the greatest peacemakers do it? They took quality time in prayer or meditation every day. The reason we don’t do that is that when you sit down to meditate you have to face yourself and all the violence inside you. If you’re going to give your life for a new world of peace you have to let go of your anger, bitterness, resentment. All the religious traditions teach that – allowing your heart to be disarmed and allowing the springs of peace to bubble up within you so you can radiate personally the peace you seek politically.

Have you encountered violence within yourself?

Sure. Especially as I get older I recognize the violence within me. My take is that we’re now completely addicted to violence, the whole human race. We’re all brainwashed to be violent as kids, as families, as schools. Now after thousands of years of violence we’ve instituted it to the point where we say, “Yeah, it’s okay to drop a nuclear bomb.” I have priests and ministers telling me that all the time. We need to become sober people of nonviolence. Our churches and peace groups should be like 12-step groups where we begin the process of becoming nonviolent.

I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on this. The minute you stand up in the U.S. and speak out against the wars in the U.S. and Afghanistan you get renounced, you get hurt, harassed, persecuted. I’ve been attacked by thousands of people. The culture tells me to retaliate or to nurse resentment. But I want to break the cycle of violence in my own heart even as I work to abolish nuclear weapons.

What does that look like – breaking the cycle of violence in your own heart?

I’ll give you an example. I know Archbishop Desmond Tutu. I always joke that this guy is embarrassing. He’s so much fun to be with. He’s laughing all the time. But he was under death threats even as a boy. His whole life he’s been attacked. He should be a raging, angry lunatic. And yet he’s joyful and peaceful and loving and he’s changing the world.

I find the same things in Gandhi. His mere presence was contagious. Everybody wanted to be with him; he was such a delightful, loving, funny guy even though he was trying to overthrow the British empire. Every day of his life he read from the Sermon on the Mount. He said it was the greatest teaching on how to be a person of nonviolence in history. These are spectacular teachings. Jesus says, blessed are the peacemakers, love your enemies, hunger and thirst for righteousness, be as compassionate as God. And he says, “You have heard it said, ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ I say, do not even get angry.” If anger is at the root of your nonviolence, it won’t sustain you for the long haul. Then Jesus recommends two other emotions. He says you have to be people who mourn because your sisters and brothers around the world are dying. We in North America have to learn to grieve. Jesus also says, cultivate joy. Blessed are you when they persecute you for justice. Rejoice and be glad. Gandhi and Tutu both decided to conserve their anger, to turn it down and channel it into positive actions. But they actively took time every day to grieve and cultivate joy.

What spiritual practices sustain you?

I spend 30 minutes of meditation every day in solitude. I try to really breathe in peace and allow the God of peace to love me and disarm my heart. As a Christian I sit with the nonviolent Jesus and I try to let go or pray over my anger, wounds, resentment, bitterness, and receive the gifts of peace. I also read the gospels. I still think they’re the most radical thing there is, especially the Sermon on the Mount. The third thing is friends. I think you have to have like-minded friends involved in the peace and justice movement to sustain you. Ideally you should be in a community.

Public action itself can also be a source of new energy, but that comes after all these others. I always have some public event coming up – a serious demonstration, which usually involves a risk. I’ve been in and out of court for years and I’ve spent time in jail. Here in New Mexico we also hold a vigil every year at Los Alamos, the birthplace of the atomic bomb. I’m in a lot of trouble with the church authorities for doing this public witness, so that’s no joke for me. These events have a cost. But there’s something that sustains me there.

Public action itself can also be a source of new energy, but that comes after all these others. I always have some public event coming up – a serious demonstration, which usually involves a risk. I’ve been in and out of court for years and I’ve spent time in jail. Here in New Mexico we also hold a vigil every year at Los Alamos, the birthplace of the atomic bomb. I’m in a lot of trouble with the church authorities for doing this public witness, so that’s no joke for me. These events have a cost. But there’s something that sustains me there.

What’s the longest you’ve been in jail?

About nine months. Three friends and I hammered on a nuclear fighter bomber in North Carolina in 1993. They put me and Philip Berrigan in a tiny county jail. We never graduated to prison. We were in a cell the size of a bathroom for nine months. I never went outdoors except for the two or three times we went to court. Once a week we had a 15-minute visit. It was very hard for me, and I think that’s cruel and unusual punishment. Phillip and I developed a kind of monastic rhythm. We did Bible study in morning, read our mail, had lunch, did a writing session for an hour and then we had free time in the afternoon – I’m talking about free time in a nine-by-ten-foot space. After a month of this we realized we needed a formal check-in time to see how each other was doing, so at 6 p.m. we would ask, how was your day? We were trying to be nonviolent toward each other, but it was hard, and it got harder as time went on. We were expecting to go to prison for 10 years. But we also felt a profound experience of the God of peace.

You said earlier that in balancing contemplation and action, you need more time for contemplation?

We’re working to convert the systemic injustice of war, but even more importantly we are hoping to welcome a whole new world of peace and justice, a world without war or poverty or nuclear weapons or climate change, and that is beyond us. That is a gift from the God of peace. So this is a spiritual work. We’re talking about a new kind of mysticism that has radical social and economic and political implications that are a threat to the U.S. government and the forces of war and death in the world.

For me as a Christian that means trying to live my day – morning, noon and night – with the nonviolent Jesus. Now that may sound goofy or pious, but it really helps when you’re under arrest, when you have chains around you. If you think, “I’m not alone, I’m with the nonviolent Jesus,” then you’re not afraid, you remember your love, you feel profoundly centred and mindful and peaceful, and then you can even go to prison or be killed like Martin Luther King Jr. and be peaceful. It’s taken me a whole life to even see the possibility of that.

In apathetic times, how does one organize people for peace?

The same as in non-apathetic times. However, I have never experienced non-apathetic times. A billion people are starving, 30 wars are being waged and nuclear weapons and climate change threaten us all. Yet most of us living with the com- forts of the First World have no need or interest to get off the couch, turn off the TV and head out to the streets and organize meetings.

So we need to do whatever we can to wake people up, help build the movement for disarmament and justice, and stay involved in the struggle. Besides being activists, we have to be organizers. We need to call for a meeting, put out the tables and chairs, advertise the event, bring coffee and cookies, set the agenda and get people mobilized. We don’t have to worry about numbers. A handful of committed people can change the world. We just have to do the work, by bringing people together and inspiring them to take public action. Every time I’ve done this over the decades I’ve seen people who weren’t otherwise interested get involved. They just needed someone to call them together and get them interested in doing something. I’m amazed more people aren’t organizing actions for disarmament and justice. I hope everyone will try it. Do it as a Gandhian experiment in truth, and watch the outcome. You may be surprised. We have more power than we realize.

So we need to do whatever we can to wake people up, help build the movement for disarmament and justice, and stay involved in the struggle. Besides being activists, we have to be organizers. We need to call for a meeting, put out the tables and chairs, advertise the event, bring coffee and cookies, set the agenda and get people mobilized. We don’t have to worry about numbers. A handful of committed people can change the world. We just have to do the work, by bringing people together and inspiring them to take public action. Every time I’ve done this over the decades I’ve seen people who weren’t otherwise interested get involved. They just needed someone to call them together and get them interested in doing something. I’m amazed more people aren’t organizing actions for disarmament and justice. I hope everyone will try it. Do it as a Gandhian experiment in truth, and watch the outcome. You may be surprised. We have more power than we realize.

Josiah Neufeld is a writer and journalist currently working on an MFA in creative writing at the University of British Columbia. He cultivates inner peace walking among the giant cedars and Douglas firs near his home.

Sorry, comments are closed.