Another American Nightmare: The Burden of Oppression during a Pandemic

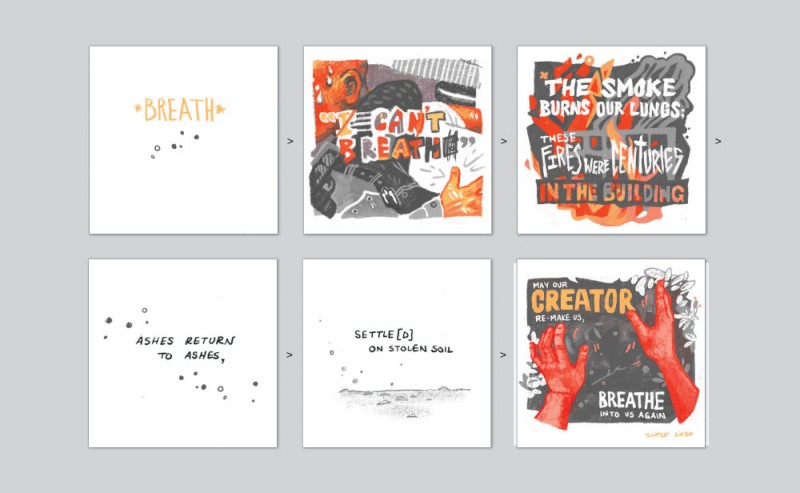

“Breath” by Nicole Wolf | This series was designed as a side-scrolling comic for Instagram – “a quieter piece, like a prayer.”

On a mid-March evening, when New York was officially under stay at home orders, I began compiling a list of Black people who had died from COVID-19.

“. . . And when I speak, I don’t speak as a Democrat. Or a Republican. Nor an American. I speak as a victim of America’s so-called democracy. You and I have never seen democracy – all we’ve seen is hypocrisy. When we open our eyes today and look around America, we see America, not through the eyes of someone who has enjoyed the fruits of Americanism. We see America through the eyes of someone who has been the victim of Americanism. We don’t see any American dream. We’ve experienced only the American nightmare.” – Malcolm X, 1964, “The Ballot or the Bullet”

On a mid-March evening, when New York was officially under stay at home orders, I began compiling a list of Black people who had died from COVID-19. I had about six names at the time, and they all had something in common: they were all denied a COVID-19 test multiple times though they were displaying classic symptoms of the virus.

Rana Zoe Mungin, a thirty-year-old teacher from Brooklyn, New York was one of the names on my list, and she weighed heavy on my heart. She was a Black woman, my age, and a teacher – my former career in a past life. After being denied a coronavirus test twice, Rana returned to the hospital eight days later with a fever. She was finally tested during her third odyssey to the hospital and was intubated for over a month.

Tragically, Rana Mungin fought a long fight but lost her life.

I began making a list of Black people dying from the virus early on because the history of the United States and its systems of oppression show me that a racial lens is required – and those who think otherwise are fortunate to not be victims of Americanism.

Victims of Americanism during this global pandemic – Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people – understand why race and class cannot be removed from the conversation, regardless of where we live in the world because white supremacy knows no borders. The systems and institutions purported to serve and improve the lives of U.S. citizens – healthcare, education, and criminal justice – are poisoned by white supremacy and harmful to BIPOC.

As COVID-19 began aggressively spreading across large U.S. cities, the shared sentiment from government officials was that this virus did not discriminate. On the contrary, we quickly learned that COVID-19’s primary victims are Black and Indigenous people, which is not surprising when historical context is examined.

The land of the United States was stolen from Indigenous people through invasion and violence by European colonizers. Enslaved Africans were forced into bondage to build the capitalism that has driven the United States since its inception. COVID-19 has brought senseless loss and grief, but it is the racist history of the United States and its violence against Black and Indigenous people that has caused these communities to suffer disproportionately.

The Real Underlying Conditions

In an April COVID-19 press conference, the Surgeon General of the United States, Jerome Adams, suggested that the disproportionate deaths in Black and Latinx communities are caused by higher rates of tobacco, drugs, and alcohol consumption. This statement was medical negligence. What he conveniently failed to mention is the historical and ongoing role of the federal government in causing underlying health conditions.

He did not mention racist housing policies, like redlining, which have forced Black Americans to live in low-income housing and purchase homes in the most defective areas of a city where landfills, coal plants, and factories were their backyards. He did not mention that these practices have compounded and led to higher rates of asthma, high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and kidney issues in Black communities.

Surgeon General Adams also failed to acknowledge disparities in healthcare. BIPOC have less access to quality healthcare, and Black people are less likely to trust medical professionals. In a 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, 40% of first- and second-year medical students believed dangerous myths, like the nerve endings of Black people are less sensitive than those of white people. They also believed that Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s, making them less susceptible to pain.

Would Rana Zoe be alive today if she was believed about her inability to breathe on her first trip to the hospital?

In addition to the physical health issues that COVID-19 presents to Black and Indigenous communities, the virus exacerbates social injustices. Surgeon General Adams did not mention that working from home is a privilege afforded to few. According to an Economic Policy Institute survey, only 16.2% of Latinx people and 19.7% of Black Americans are currently able to work from home.

For undocumented Latinx people, the risks of COVID-19 are further exacerbated. As ICE continues to pounce on undocumented immigrants, they are less likely to seek medical attention for fear of being detained.

And Indigenous communities, who have been forced off of their lands and worked hard to maintain their communities over the years, continue to suffer disproportionately from lack of access to clean water, food, and other services.

These are the underlying conditions that make it difficult to win the battle against COVID-19. And the list could go on and on.

Relentless Grief Demands Rest

As a society, we have to ask ourselves: What does it mean that COVID-19 disproportionately affects BIPOC? What does it mean that the people whose land we occupy and the workers who keep the capitalist machine of America running experience insufferable oppression? I don’t have the answers, but I want to believe in the unprecedented movement I’ve witnessed over the last few weeks and months.

Across the streets of America, there is a rallying cry for justice and the crucifixion of white supremacy. George Floyd, a Black man, murdered by the state in Minneapolis, Minnesota for the world to see, has called the world to action. The Black Lives Matter uprisings outside our windows are not only in his name, but Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Atatiana Jefferson, Sandra Bland, Rayshard Brooks, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Nina Pop, and so many, many more. We honour them.

How can Black people regroup after experiencing relentless death and grief at the hands of four hundred plus years of oppression?

To answer this question, I turned to Rachel Ricketts, a racial justice educator, spiritual activist, healer, and author. Ricketts named that “we need to allow ourselves to grieve and to acknowledge that we are in a time of grief. Grief can be an illuminating entrance to understand what we’re feeling about what’s going on.”

James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” Ricketts offered her own version relating to grief: “To be Black anywhere in the world is to be in a state of grief all the time.”

Black people are forced to grieve because of institutions and systems of oppression. “Black people have been socialized to work ourselves to death,” says Ricketts, referencing our enslaved ancestors. “Grieving really demands rest.” In the stillness is where we can be with and feel our feelings.

It’s important to acknowledge that grief is not only sadness but is a range of complex emotions. Ricketts’ definition of grief is a normal, natural human emotional response to loss, change, or lack of change. “In this heightened time, with a pandemic within a pandemic, there’s deep sadness, anger, rage, frustration, but there’s also hope, opportunity, and maybe a sense of relief in some way. And we’re experiencing it all at once,” says Ricketts.

She notes that she doesn’t expect to see a massive change in her lifetime. She has had to release whatever the outcome may be and focus on doing what she’s here to do. “A huge part of [my work] as a Black person is to care for myself,” says Ricketts. “Allowing myself to grieve is part of the resistance.”

Ricketts wants to create a world where white people are doing the work to dismantle the systems that they’ve created, while BIPOC – specifically Black and Indigenous people – rest. Not only physically rest, but mentally and emotionally. Ricketts adds that when we sit in the stillness with the depths of our grief, it may seem unbearable, but it won’t just be our own – it will also be the grief of our family members and ancestors.

This can be intimidating. It may feel like if you come undone, you won’t be able to put yourself back together. Ricketts relates and shares compassion for that experience but counters, saying, “Look at what you’ve had to endure. We are the most resilient people on the planet because we’ve been forced to be.” Rest and caring for ourselves is as crucial as protesting and being in the streets, says Ricketts. “We deserve to rest, we deserve to grieve and mourn for ourselves, our families, and our ancestors.”

Renée Cherez is a moo-loving, mermaid-believing empath seeking truth, justice, and freedom. She is based in New York.

Start the Discussion