O, Brother Jian, Where Art Thou?

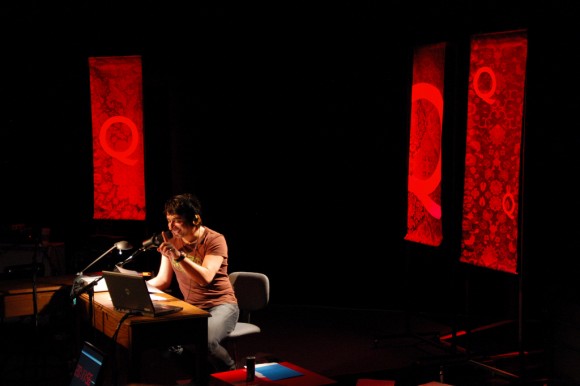

Credit: Derek K. Miller, https://www.flickr.com/photos/penmachine/3389479872/

Messes in the dark make headlines every morning

Everyone makes mistakes like it’s the only way they learn.

Be careful ‘cause the lights come on without a warning

People seem so confused when they’re caught with some bullshit

from “Messes” by David Bazan

The precipitous collapse of Jian Ghomeshi’s career has been equal parts scandal and spectacle, spontaneously generating piles of cheap humour and plenty of opportunities to feel self-righteous.

I’ve logged well over a thousand hours of listening to him on Q over the years and have long been impressed, not only by the caliber of the guests he and his team manage to land, but by the steadily improving quality of Ghomeshi’s interview skills. I often listened to Q not just for what he was doing but to try to understand how he did what he did – tone of voice, inflection, quick-thinking responses to interviewees, improvising questions that could sometimes get jaded celebrities off their well-worn scripts and speaking off-the-cuff. In the days after the story broke I cracked a handful of easy jokes at Ghomeshi’s expense, mostly to hide how hurt I felt about it all and to mask fact that I actually really miss the guy.

It may well be that you’ve grown a bit tired of hearing about Ghomeshi, but before the scandal broke, Q was a bona fide CBC hit, not only in Canada, but across the border, too. The New York Times called it “amazingly good – especially for a daily program,” and The Washington Post called it “the most popular new arts and culture radio show in America.”

Losing kindness

Ghomeshi was fired at the end of October, and what started out looking like “he said/she said” quickly turned into “and so did she/and she/and she” until we got all the way up to nine women saying Ghomeshi’s, ahem, “sexual tastes” were actually terrifying cases of violence and abuse. Police have so far charged him with seven counts of sexual assault and one of overcoming resistance by choking.

The usual cadre of sanctimonious trolls and haters and their servile, caustic missives established the prevalent tone of the conversation, once again demonstrating that social media is quick, easy, often unreliable, and almost entirely anathema to self-reflection and sustained, genuine thought. But top-notch reporters like Carol Off and Anna Maria Tremonti, two of CBC’s very best, stepped up and offered fine, professional journalism on the complex, volatile story, digging for depth, context, and social analysis rather than more and more lascivious details about Ghomeshi and his rough sex life.

Curiously absent from the analysis so far is any real discussion about sex. In his famous, now-deleted Facebook letter, which he posted just before the story broke, Ghomeshi said that “sexual preferences are a human right.” As the layers of the story unfolded, that which Ghomeshi described as “rough sex” was, for these women, violent and abusive, but so far the closest we have come to moral analysis is questioning whether or not what took place was consensual. We have pawned all of the other deeper things that sex can be – communicative, healing, procreative, and genuinely loving; nested within immeasurable relational layers of family, community and culture – for the great prize of liberation, its limits only defined by words like “consent” and “rights.” “Losing kindness,” wrote Lao-tzu, “they turn to justness.”

Rights and freedoms

With sex so gloriously liberated, we’re promised that the shifting tectonic plates that comprise our culture’s understanding of sexuality can be safely managed by a few sheaves of legal documents that define terms like “partner” and “consent.” Self-centred assumptions about supposed “rights” convince us to go ahead, strip down, and get it on with whomever you want, with the assumption that Ghomeshi and his girlfriends and all the rest of us will be just fine. It’s 2014, after all, where not only have we cast off all the restrictive, puritanical notions about sexuality, we’ve also outgrown our forebears’ tendencies towards misogyny, barbarism, cruelty, and abuse, right? Right?

If you’ve decided that uninhibited sexual pleasure is your life’s number one goal and primary pursuit, then consider yourself to have been born in the right time and the right place, so long as you make sure it’s all consensual. If, however, your life includes more than simply getting your jollies with your genitals; if it includes things like love, friendship, work, vocation, community, eating healthy, and the practice of any number of other non-erotic pastimes; if your life involves more than just you and whatever consenting sexual partner(s) you happen to be naked with at the time, you have to consider that your supposedly liberated sexuality is, in fact, necessarily bounded by an immeasurably complex fabric of commitments and responsibilities. The only thing we’ve truly liberated sex from is making babies. That and the risk of catching some sort of exotic-sounding venereal disease. Because in every other conceivable emotional, social, psychological, and spiritual way, sex is just as dangerous as it has always been.

In fact, safe sex may be actually more dangerous than its supposedly “unsafe” iteration because it has become wholly unmoored. Every wisdom tradition, religious or otherwise, tells you that full, rich living, including sexual expression, requires disciplining one’s desires and ordering one’s loves. But the isolated, individual freedom of uninhibited sexual desire is brutish, cold, and ultimately lonely. We cannot solve the problem of privileged men and their sexual abuse habits by increased education on the precise definition of “consent.” The problem is much bigger than Ghomeshi, bigger than his (allegedly) abusive sexual style, bigger than a lack of education or learning or cultural sensitivity.

Dislocated from the meaningful contexts of community and history, unbounded sexual liberation naturally devolves into all kinds of selfishness, violence, and abuse. Common sense tells us everyone wants freedom, and we assume that we deserve it and are entitled to it even if we can’t articulate what it is or what it actually means. Our “right” to freedom means we don’t have to listen to anyone who tells us what we can or cannot do, sexually or otherwise. That is until someone like Ghomeshi crosses an unarticulated boundary line, giving everyone the chance to point a finger and say what a creep that guy is. Ghomeshi’s “right” to sex and privacy have clashed with the rights of at least nine women to not be hit, not to mention the public’s right to know when our public figures behave scandalously, and the media’s right to scrutinize and expose the scintillating, gossipy details of one of its own celebrities.

However boldly Ghomeshi might otherwise claim, sex is not a right. He was never entitled to sex, and neither am I and neither are you. The state does not need to ensure your access to sex, and the laws are not in place to protect your private sense of what sex is and what it’s for. Sex is a gratuitous gift that only makes sense in the context of love, not freedom.

Love above all

In case you’re as confused as I am about what “love” actually means, we all at least implicitly know that consent is not the same thing as love. Our sense of “love” is so saturated with obsessive sexuality and muddled with sentimentality and sales pitches that, were it not for its genuine practice, it would be a dead word. I love the new My Brightest Diamond album, so much better than Taylor Swift, but heck, she sings about love, too; I loved John Favareau’s movie Chef; for the past seven years I’ve loved listening to Q with Jian Ghomeshi – oh, and I love Erika, and the three young kids we made together.

It’s worth asking around about this. Start by speaking to a new mother with a newborn in her arms: ask her about love. Ask the husband who has cared for his wife the past three decades since she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Talk to anyone who lives in a L’Arche community, or an adult child who invites their aging parents to move in. Ask the parents whose two-year-old has cancer. I guarantee that not one of them will even so much as mention the word “rights,” that the love they recount will have very little flash and glamour, but plenty of ballast, routine, care, and the kind of self-less giving that ties sacrificial love to things like kindness, patience, and hope. Genuine love doesn’t provide all freedom’s easy off-ramps, but in the clear light of the authentic practice of love, the promises of sexual freedom look embarrassing and frivolous.

Ours is a sexually liberated time, it’s true, but if the only outrage we can muster is over a disputed definition of “consent,” we’re straining out gnats to swallow the camel whole. Like all the other mammals, we humans have an instinct for the mechanics of sex, and our liberated sexuality provides us with abundant possibilities and opportunities for fucking: even Jian can attest to that. But check with any one of his accusers, the women on the receiving end of his (alleged) unsolicited punching, and this much will be absolutely clear: we are drifting further and further away from love.

Kurt Armstrong is a handyman, lay minister at Saint Margaret’s Anglican, and freelance writer. He and his wife have three kids, and they live in Winnipeg.

Kurt Armstrong is a handyman, lay minister at Saint Margaret’s Anglican, and freelance writer. He and his wife have three kids, and they live in Winnipeg.

4 Comments

Sorry, comments are closed.

To Kurt – my colleague, co-contributor, and friend:

My best response to this article would be in the form of an giant audible sigh.

Because this is an old story. And I am tired of hearing it.

I heard it as a child sitting in a church pew, being told of Eve’s sin and the culpability I hold within that story as a woman. I heard it everyday in high school when the dress code dictated how much of my knee was allowed to be visible at any given time. I heard it at Christian College when the Promise Keepers guy told us that every 3 days sperm build so much in men’s testicles that they literally go crazy, so therefore we shouldn’t wear tank tops.

The problem here is not the so-called darkness and dangers of a “free” sexuality, but in the fierce holding of power over women’s bodies which have been rampant throughout time; a power which I hear echoing within your words.

This piece does a grave disservice by assuming that casual sexual activities are carried out without thought to community, kindness, or responsibility. In fact, the discourse and philosophy of consent is rooted within these three. Consent recognizes no person holds power over another; no one person’s desires are more important, no one can truly act out the scenarios of “unbridled” sexuality to which you somewhat bizarrely allude. Your constant reference to consentful-yet-uninhibited sexual behavior makes little logistical sense.

To assume that all sexual encounters outside a long-term context are devoid of love . . . I don’t know what to say. It is simply not true.

I can’t help but connect your words with the words of my church, of my high school, of my college, all of which were precisely targeted at controlling my body as a woman. I only hear social control. I only hear a shaming placed upon me and my sexual activities. I hear patriarchy.

To begrudge sexual liberation in the name of love is to begrudge love itself. Real love is neither controlling nor coersive; it is based upon consent, community, kindness and responsibility. That is my understanding of Christlike love, within both casual and long-term encounters. To dictate the sexual behavior of others, to measure the worth of every intimate encounter based upon the time invested and/or number of babies created, is beyond our scope of authority. And blaming the sex-positive movement for being at fault here ultimately and unsurprisigngly lets Ghomeshi and others like him off of the hook.

Again, this is an old story.

Bre Woligroski Winnipeg January 21st, 2015 9:56am

Actually, you are both talking about the same thing. I see no disconnect.

I like this overview and am happy that someone has finally brought up the

elephant in the room, sex.

Thank-you, Kurt, for starting a much-needed discussion.

Shannon in Ottawa

Shannon Lee Mannion Ottawa, ON January 22nd, 2015 4:57am

Yo Kurt,

Firstly, apologies for doing this online comment thing as opposed to chatting in person: I’d far sooner talk this over brews (I feel like writing can really distort the tone of the message, especially on subjects this personal).

Just wanted to echo Bre’s thoughts on the matter. I find the rhetoric around sexual intimacy in this piece to be a bit troublesome. Basically, I’m failing to see evidence for why “love” expressed through physical intimacy necessitates long-term commitment. I’ve had a few plutonic friends who have only been in my life for a couple of months. I certainly don’t love them less because I’ve moved to a different city, or have simply parted ways.

Not sure why it can’t be the same with physical intimacy; I’m just not sure why we can be “emotionally” intimate with dozens of friends in a lifetime but not accompany that with “physical” intimacy. Unless, of course, there’s a fundamental divide between “spirit” and “matter.” Which I don’t personally buy (but maybe that’s why I’m not a Christian anymore). I’d suggest chatting with some folks in polyamorous relationships if you want to hear more about this stuff.

This sort of sentence – “the isolated, individual freedom of uninhibited sexual desire is brutish, cold, and ultimately lonely” – seems far too sweeping to be justified.

Also, I respect the discussion, but the conflation of sexual promiscuity with an ongoing court case concerning abuse and psychological manipulation seems a bit … soon. Ghomeshi’s actions had a sexual component to them, but were fundamentally criminal. Not fair to combine the two and maybe a value judgment on the former.

Hope this doesn’t come off as snarky or patronizing, dude. – James

James Wilt Calgary, AB January 22nd, 2015 1:40pm

A very thoughtful, eloquent essay. Thank you, and thanks for pointing out the “elephant in the room” — love.

Diane Engelstad Fenelon Falls ON February 5th, 2015 10:50pm