Three stations of the activist soul

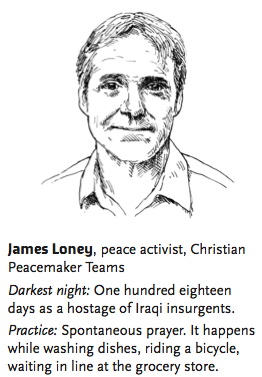

James Loney answers my questions with care, judiciously scouting the path each sentence will take before he speaks.

I’ve reached him by phone at a California monastery. He’s come here for a month of quiet self-examination, to reflect on his work as an activist, to heal from a recent break-up with his long-time partner, and to search for his way forward.

This scrupulous habit of self-examination gives weight to Loney’s words. It may also be why it took him three years to write a book about his four-month ordeal as a prisoner of Iraqi insurgents.

I’ve interviewed Loney once before, four years ago, when the Catholic Archdiocese of Winnipeg invited him to speak at a social justice conference, then uninvited him at the last minute because he is openly gay.

I want to hear Loney’s story. I don’t need to hear the facts of his life, public as they have become. I need to hear the story of his life, the tribulations of this activist’s inner journey.

Loney begins. “I was naturally inclined toward idealism.” He joined the Catholic Worker movement in his mid-20s and, together with two friends, started Zacchaeus House, a community that welcomed people in need of housing. The community quickly grew to include six households, a saw-mill, a bakery and a newspaper.

Even Loney is astounded when he thinks about everything he did in those ambitious days. Twenty years later, he has come to recognize a deep hurt that helped drive this activism.

“The presence of God was very real and tangible, but at the same time I had this deep abiding sense of being unworthy, of being disordered as a young gay [man],” says Loney. “I was afraid of this desire within me and afraid to accept that it could be true.”

Three stages on the journey

I spoke to several other activists – lifetime pursuers of peace, justice, social and ecological change. The stories I heard didn’t all follow the same plot or match some kind of template, but common elements emerged that I’ve ordered according to three stages of development.

I’m drawing upon my conversation with Loraine McKenzie Shepherd, a United Church minister in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and how she illustrates her own spiritual development. She uses the three ways of reading Scripture de- scribed by French philosopher and theologian Paul Ricoeur.

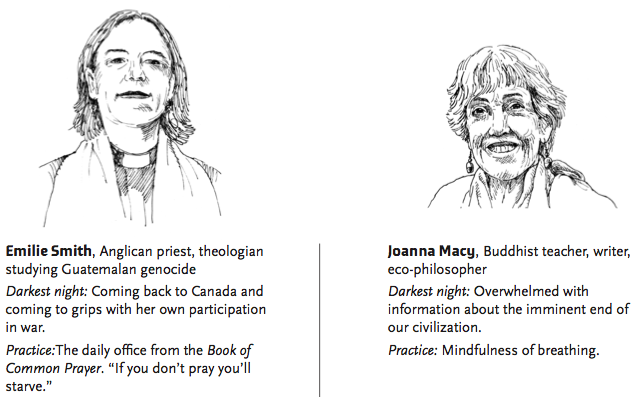

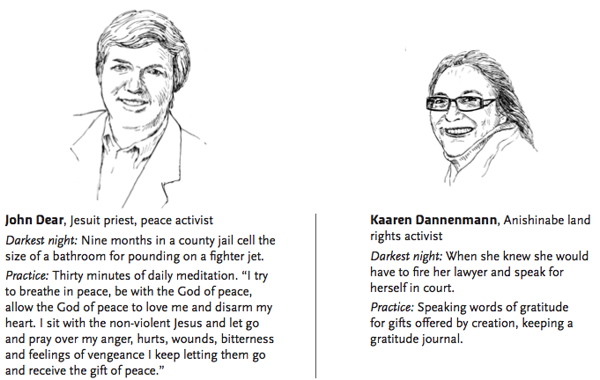

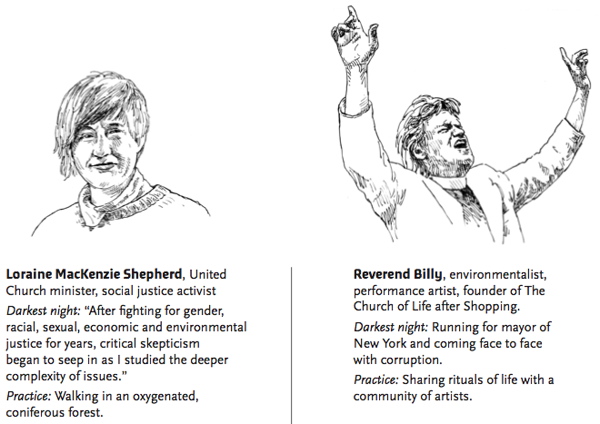

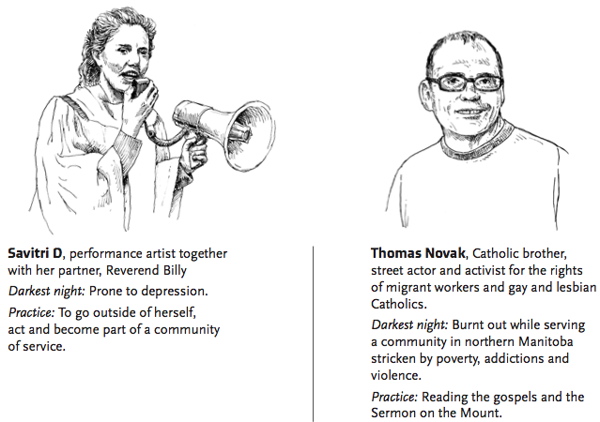

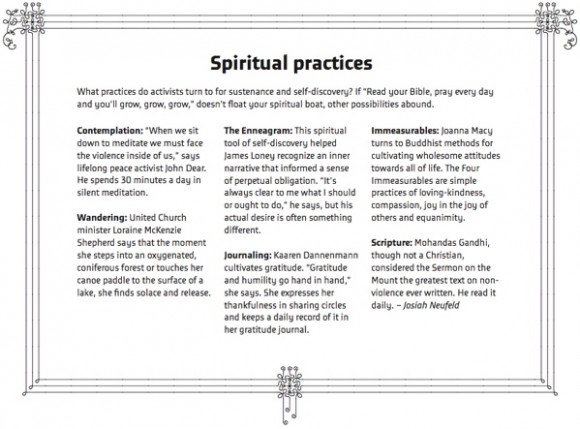

Geez asked nine activists about their darkest night and about the spiritual practices that sustain them.

All illustrations: Darryl Brown

The first stage of reading is literal and relatively naïve; here you believe that with enough faith everything will transpire according to God’s will.

The second stage involves a critical and questioning perspective; the reader establishes a distance from the text in order to analyze it.

The third stage is what Ricour calls a “second naiveté.”

The reader returns to Scripture trusting in its capacity to guide; this is a faith in spite of the questions. It’s not a literal reading, but one that embraces the symbolic or mystical meanings.

Brian McLaren, a popular theologian for the emerging church, explores similar seasons of spiritual growth in his newest book, Naked Spirituality. He charts the growth in terms of four movements: simplicity, complexity, perplexity and harmony. Less philosophical but much more accessible than Ricoeur, McLaren draws on the work of people such as James W. Fowler, Soren Kierkegaard and William Blake who have mapped phases in the journey of the spirit.

Guided by Ricoeur and others, I’ve named three stages along the spiritual path of an activist: idealism, darkness and mystery.

Idealism: The Spirit is upon me

Idealism is a place of ignition, of fire, of energy. Here the activist encounters her calling, is galvanized by exposure to injustice or impassioned by a need. The momentum of the idealist stage can carry a person for years, even decades.

In his idealist years Loney identified himself as a radical, celibate Catholic worker, called to give his life for the healing of the world. He helped create a justice-seeking community in Toronto that welcomed people from the streets and into their homes.

Another activist, Kaaren Dannenmann, first sensed her calling when she was a child living on the shores of Trout Lake in northern Ontario. Dannenmann is an Anishinabe woman who has devoted her life to fighting for her people’s right to live on their ancestral land – land from which they were evicted in the 1920s when the Canadian government found gold there.

“I’ve known from when I was a child growing up in Trout Lake that that’s where I belong, and that’s never wavered. I knew my adult life was going to be spent working to protect that,” says Dannenmann.

Over the last 20 years Dannenmann has built at least six log cabins on Trout Lake. According to Ontario’s Ministry of National Resources, this construction is illegal. She has represented herself in court, using her trial hearings to question Canada’s treatment of First Nations people.

A great danger in the idealism stage is the development of a saviour complex says Thomas Novak. He speaks from experience. Thirty-three years ago, Novak made his vows as a Missionary Oblate of Our Lady Immaculate, and he took his his title to heart. Oblate literally means sacrifice. Assigned to a northern community torn by addiction and violence, Novak worked non-stop for four years before he burned out. “I thought I could make a really big change. I was going to be a saviour,” he says.

Novak points out that Jesus himself evolved as an activist. At the beginning of each gospel, Novak sees an idealist Jesus brimming with passion and energy, on a mission to heal everyone he can lay hands on. When the Spirit drives him into the desert, he’s tempted with a career as a celebrity saviour. “Jesus had to come to grips with the fact that he was going to be a failure,” says Novak. “That’s really the story of Jesus’ life.”

Darkness: Why have you forsaken me?

“When I try to raise my thoughts to Heaven there is such convicting emptiness that those very thoughts return like sharp knives and hurt my very soul. I am told God loves me – and yet the reality of darkness and coldness and emptiness is so great that nothing touches my soul. Did I make a mistake in surrendering blindly to the Call of the Sacred Heart?”

When these words were published 10 years after the writer’s death, the world was shocked to learn that such aching doubt and spiritual loneliness had been the daily bread of one of the most inspiring figures of the century.

Mother Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 for her work among the poorest outcasts of India. When she died, the world called her a saint. Ten years later, letters she had wanted destroyed revealed her long dark night of the soul. With the exception of a five-week window, this sense of abandonment by God lasted from her arrival in India until her death 38 years later.

On the eve of his own death, deserted and betrayed by his closest friends, Jesus questioned the meaning of his life and the reason for his impending death. He begged for an escape but heard only silence. In his novel Silence, Shusaku Endo depicted this divine indifference with the recurring image of cold waves washing a darkened beach.

During the dark night God may retreat, fall silent or vanish completely. Ideals often collapse. Questions flourish; tried and true answers no longer assuage.

Even activists who don’t pin their hopes on a deity are prone to this darkness. Buddhist teacher, writer and eco-philosopher Joanna Macy says her darkest period came when her activism overwhelmed her with the knowledge that humans truly had the potential to destroy their world.

“My inner defenses against knowing that crumbled,” Macy says. In her memoir she likens the feeling to the “collapse of an inner scaffolding.” Even as she continued to join public protests, attend anti-nuclear conferences and fight nuclear power companies in court, she felt the inner slip of despair. At night she dreamed of apocalypse.

But even darker than abandonment or hopelessness is the night of guilt. Novak has counselled priests and nuns who once ran Canada’s residential schools. Their pain can be excruciating, he says. Residential schools were operated by churches in Canada with the goal of purging aboriginal identities from a generation of children.

“We know that some staff of residential schools did evil things,” says Novak, referencing many documented cases of physical, sexual and psychological abuse. “And we know that many staff were revolted by that and really loved the children. Yet even some of those are saying, ‘I would have done it differently today.’”

As stories of trauma continue to emerge, many former staff members are recoiling from the public exposure of the suffering they caused.

“It’s a very painful thing to look at the work you’ve devoted your whole life to and to say that maybe I was doing evil and not good,” Novak says.

Mystery: Peace be with you

Darkness must precede mystery, just as death comes before resurrection. When the resurrected Jesus appears to his disciples in the gospel of John, he offers no explanation for this mystical encounter. Instead he repeats, “Peace be with you.”

The second naiveté described by Ricoeur exchanges the night of skepticism for a renewed faith, one that no longer depends on literal belief but embraces mystery. In this stage, the activist returns to Scripture with awe, reading it with a posture open to its symbolic meanings and attentive to the mysterious movement of the Spirit.

“Words are mere guideposts now, and you recognize that most people have made them hitching posts,” writes Richard Rohr in The Naked Now. Rohr is writing about what he calls non-dual thinking: “a way of seeing that refuses to eliminate the negative, the problematic, the threatening parts of everything.”

This stage does not necessarily offer answers to questions encountered during the dark night, but often provides a way to live without answers. Mother Teresa never overcame her sense of forsakenness. Instead she learned to carry it with her, abandoning neither her faith nor her work.

In 1979 Macy wrote an essay she titled “How to deal with despair.” In it she told how, instead of turning her back on her tremendous grief for the earth, she learned to draw strength from it, to see it as a sign of her connectedness to all living things. She said in an email to Geez that her dark night engendered a “trust in the beauty of life and the power of the human ability to choose.”

Know yourself

Loney has travelled a personal yet common journey. He’s moved from an energetic idealism through periods of despair and into a sober confidence amid uncertainty. At 47, he can see how a combination of faith, idealism and feelings of unworthiness propelled what he calls the “radical gospel life project” of his youth.

In many ways his path to self-discovery as an activist parallels his journey towards accepting himself as a gay man. How did he make those discoveries, I ask. When? Where?

Loney is silent at the other end of the line. I fear that I’ve pushed him into uncomfortable territory. When he speaks, finally, it is with his usual deliberation. Nothing happened overnight; it was all a process, he says. It began at an intellectual level; Loney was 26 when, at a public lecture, he heard Catholic theologian John McNeill deconstruct the Christian theology that condemned homosexuality. For the first time Loney considered the possibility that love between two men or two women could be as sacred and beautiful as love between a man and a woman.

“I thought, wow, maybe the whole paradigm that I’ve been given is wrong,” Loney recalls. He began to read and study the topic for himself, a process that lasted several years. Only once he was able to counter his intellectual objections did Loney begin to open his heart and then his body to the truth of his sexuality.

“I suppose in a way it mirrored my activism,” he says. “I started with this idea of the world being one thing and I discovered that the narrative I had been given about the world wasn’t true, and when I accepted that I began to live differently.”

It has always been clear to Loney what he should or ought to do. “It’s much less clear to me what my actual desire is, what I want to do,” he says. “I’ve struggled in my activism to get in touch with my own passion or deepest desire to let my activism flow from that.

Each of us, whether we call ourselves activists or simply people of action, must find our own inner road. Often we stumble upon it in darkness.

Josiah Neufeld is a contributing writer to Geez magazine. He lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.