This Is My Body: Knitting as a Spiritual Discipline against Fatphobia

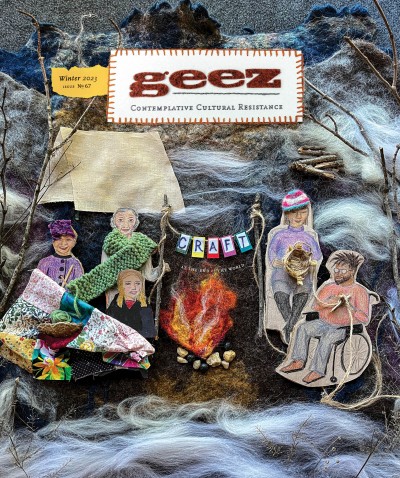

From series “Make Beauty Not War” by Michelle Both with Tora Klassen, November 2022.

To say that I start and end most days with knitting probably conjures up much more bucolic images in your head than are accurate.

Usually, I am groggily giving in to the demands of a toddler for breakfast before settling at the messy table with coffee and my knitting. Most mornings I need to drink half the cup before my hands remember how to hold the yarn and needles and begin the gentle routine. Not so glamorous after all. To be sure, knitting calms my sleep-addled brain with those movements, and provides quiet, interesting activity in the evening when the household settles again.

These are the meditative benefits of craft which are most commonly spoken about, especially in connection to spirituality. But there are other aspects to knitting, besides the quieting of a restless soul, which might also be described as spiritual. Making garments for my body, my real body and not a fantasy one, is a reminder of the goodness of my body and God’s goodness in creating it. Crafting breaks into the busyness of daily life to remind me that I am already enough.

For the most part, society tells me my body is valuable: I am white, have access to insured medical care when I need it, and have no disconnect between my sex or gender and cultural expectations. However, I am a bit larger than you are likely to see on a magazine cover and was large enough as a teen that I was told in not-so-many words that there was no point in me continuing ballet. For a long time I did not question why I could not knit a sweater in my size without adjustments.

Perhaps many of you reading this piece have painful memories of social exclusion and prejudice on the basis of your identity or body. Those with larger bodies may share the experience of a healthcare provider disregarding their pain and symptoms, instead prescribing weight loss as their sole treatment, or of having a doctor fail to see them as whole and complex patients and consequently not diagnosing a life-threatening medical condition.

I think the Christian church has exactly as much of a problem with fatphobia as its local context, more in some places than others. Our faith tradition’s relationship to embodiment is ever-intermingled with the aesthetic preferences and discourses about healthcare gained from our surrounding culture, and these often seem unchangeable.

Just as racism, ableism, sexism, transphobia, and other forms of oppression are sins of which we must individually and collectively repent, so is fatphobia. Fatphobia, like most forms of oppression, has deeply racist origins. As Sabrina Springs points out in Fearing the Black Body: Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, BMI (or the body-mass index) was developed as an actuarial table for health insurance companies and is rooted in eugenics.

Does your community value fat people as equally as thin? Take a look at the composition of your leadership, worship teams, and those providing pastoral and compassionate care for your church. Who has been excluded, and is it because of size? Fatness is not a moral failing, so deep introspection is needed here, siblings in Christ!

Knitting garments for myself has helped me to come to terms with a lot of the shame of not having an idealized body. When I patiently consider what would feel nice to wear, take the time to swatch my yarn, take true measurements of my body as it is (my proportions and dimensions, not those of a hypothetical mannequin), I am able to come into direct dialogue with my form. These days, I strive for body neutrality – trying not to hate the body I have – because body positivity can be a tiring goal.

Handmade fashion means investing love and time into the body I have. The alternatives are to craft ill-fitting garments, not make anything, or ignore an internal call to create. When I make something well-tailored rather than something that merely fits over my body, and when I prioritize breathable and sustainable fibres, I also gain the freedom to do tasks comfortably – like walking, gardening, washing the dishes, or cuddling my loved ones.

It is my great hope that everyone can come to know the joy of making clothes if they want to.

Several English translations of Psalm 139:13-14 say:

You knitted me together in my mother’s womb, I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.

The Hebrew is better translated as “you wove me” since knitting is a historically young craft. Clearly the Psalmist and the translators were apt on the power of metaphor. I create out of the love with which God first created me.

Julia de Boer (she/her) is a philosopher and yarn dyer working in Ontario. She gratefully resides by a large conservation area and is slowly learning about the plants which populate it and best gardening practices for a worse and then better climate.

Start the Discussion