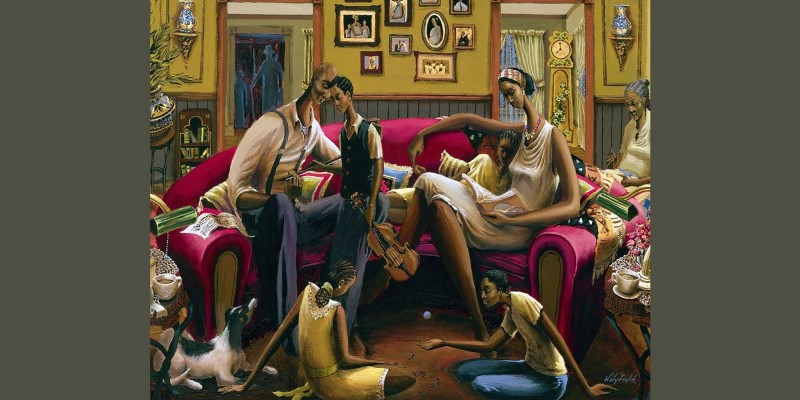

Writing and Our Craft of Black Family

“Soul’s Haven,” John Holyfield, Lithograph on paper, 30 x 24 inches.

We need stories to make it through grief.

I realize African Americans are finally in a place where we can develop clans with recognized talents, generational legacies in the public eye, developing and holding success. For many of us whose work is by nature private, we need to tell our stories well and uplift our folks. We need our memories to persist.

– Clarence Jackson

In Black Nationalist organizing, the family is the foundation of community. Strong nations are built upon the existence of vibrant family units. Creativity in the family is one of the building blocks for creativity in the hood.

I can’t write about the family I was born into without writing about grief: my mother and my younger brother have joined the Ancestors. To this day, mental and physical health challenges threaten to overwhelm us, individually and collectively.

I love you a bushel and a peck

a bushel and a peck

and a hug

around the neck.

– As sung by Linda Copeland

We need stories to make it through grief. By the rituals of repeated telling, the physical actions of those we loved are transformed – first to memory in our individual and collective minds, and then to spirit, which generates and gathers its own ability to move.

I was born into a clan of writers, a Black family that settled in Detroit, Michigan to create possibilities inside racist America. What have I learned about the craft of writing? It’s a returning. A search, a dedication – and so is family. As writers, as family, we keep coming back. It is a regularity, a ritual, a rhythm. Staying present with our shifting words, feelings, memories, each other.

Listen.

When I raise my eyes from my writing desk, I look out the window to a cluster of three trees: Father, Mother, and Son. Sometimes they dance in the wind. I look left and see my ancestral altar, pictures of my grandparents, loved ones, offerings, fragments of rock. Behind me a candle is lit.

Behind me are shelves of books. I was blessed to grow up in a house filled with books. I saw my father, Large Lee, take books with him even when visiting his own family. We inspired each other.

Listen.

By the time my brother teenaged Lee shot himself, he was a marching band drummer and two-sport athlete. He rapped on local radio shows and at high school parties. I remember a photograph of him standing in the centre of a crowd holding a microphone, a kaleidoscopic swirl of young Black Detroiters chanting, laughing, and partying around him.

Lee was my first and toughest critic. My raps and rhythms, unlike his, just weren’t good enough for the radio. I hold memories of writing together, listening together, absorbing these critical observations from my younger brother.

I supported my younger sister Lhea, who would go on to start a student organization on her college campus (called The Cypher) where hip hop and poetry could share in both spontaneous eruption and in meticulously-crafted lyricism.

I’m still trying to figure out

how someone with a

Black momma

someone who visits their cousins

every cookout and every Christmas

someone who loses sleep

over the number of genocides

can make it through

Chemical Physics

Neuroscience

Epigenetics

Theoretical Engineering

as an architect with some

sayso

and not be gunned down

by a genocidal future

on the first day of

Undergrad

– Lhea J Love, “Issues in Higher Education”

As Lhea and I began to explore poetry, my father would pull out poems from his files. He had decades of poetry, unpublished but intimately shared with his religious, activist, or family networks. He began writing again in the early 2000s and self-published three poetry chapbooks. This was a 10-year period when he would often stand up and offer a poem at family funerals.

We didn’t talk much about editing and publication, nor about how these transitions left holes in our hearts. But we listened to each other.

I offer the word “listen” in alignment with Cannach Macbride and Alex Rodriguez, who have been shaped by the deep listening practices of Pauline Oliveros. Listening is an act of creativity and care. I invite you to listen with a rigour that is intellectual but not necessarily academic. I invite you to listen in honour of my mother Linda.

Both of my parents were social workers who grew up in the U.S. South. They were active in Black Social Work organizing spaces – which means they studied, listened, and reflected on what family means, connecting to Nation-building inside racist America.

The Black family is the incubator of generational knowledge, traditions, values, and behaviours who serves as a protective mechanism against external threats and serves as a catalyst for the next ecological cycle.

– Tanya Smith Brice and Denise McLane-Davison, “The Strength of Black Families”

My mother’s listening and love penetrated deep. My sister Lhea told me recently, “Since (my daughter) Harper was born I think of everything mom ever taught me about letterheads, letter openers, corrective ink, the colour of ink, having books with Black characters, and the subliminals in children’s programming.”

We grew up seeing our grandmothers’ craft spaces. In reflecting upon his formal education, my father would tell us that social work school didn’t teach anything that he didn’t see my Granny do in action for her family.

In this capitalist pressure cooker, family is a trying: taking what is given, gathering resources, listening for opportunities. Both family and writing are acts of self-determination.

My folks tried to create a Black family that could navigate and thrive in a society that would try to murder their own children. They held a vision that we would find stability through education and professional success. We were introduced to afterschool programs, a caring Detroit village that nurtured Black excellence. Our young hands were busy crafting. My mother still tunes her listening to our gifts and talents so that we hear creativity and beauty in our own voices.

Our professional aims crumbled in the early 2000s under the weight of grief and loss. As we developed and faced losses at key points in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, we were unable to maintain the masks of hegemony required of us to build strictly professional lives.

Now we can’t measure anything, especially not ourselves. We shout into the page. We sing into the air. We fold ourselves into rhythms.

You have tried to fill your empty god with others’ possessions

And the obsession has left you empty.

We, therefore, empty our hearts to you.

We will love and watch you without fear.

–Large Copeland, “Our New World Order” (2003)

Listen.

This craft of writing is the offering of offerings. Each text is an altar, but not everyone approaches our words with reverence. Some people only see clutter, empty bottles, unexplained screams, lascivious gyrations. Obviously, not every reader recognizes the sacred. Especially when we are loud, violent, argumentative, or dissociated.

I don’t come from an entrepreneurial family. We didn’t talk about how to “successfully” put our words in the marketplace. But we did learn to write poems and songs that can be opened as presents. We learned how to kill the dove, its splashing blood a prayer around which we all might build and heal.

Owólabi/Will See is a Detroit, Michigan cultural organizer. He is a divorced father, a life coach, and a care worker with a passion for bringing the liberation lessons of Detroit to global audiences. He is a resident writer with Geez.

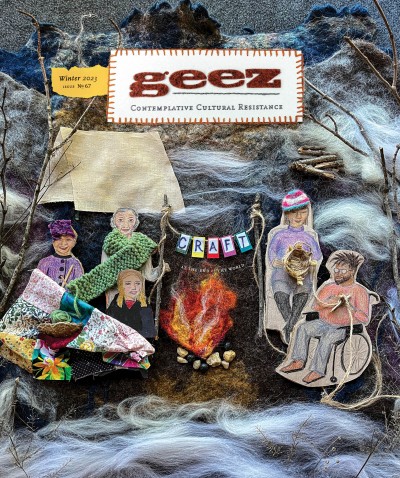

Start the Discussion