The People’s Church

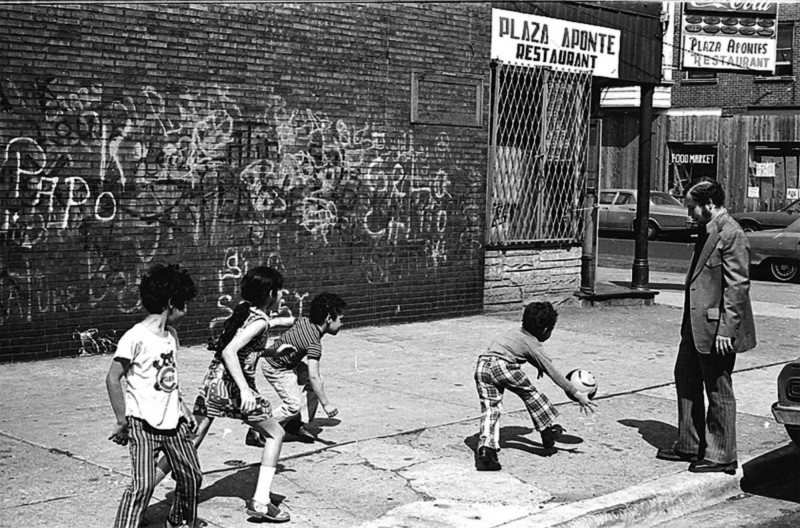

Jose (Cha-Cha) Jimenez outside of the Young Lords, and one of three aldermanic Campaign offices at Wilton and Grace, generously provided by Jimenez.

God is not dead.

God is bread.

The bread is rising!

Bread means revolution.

Organize for a new world.

Make the church a people’s church.

Wash off your brother’s blood.

The streets belong to the people.

And the church belongs to the streets.

In the midst of occupied territory,

The liberated zone is here.

—The New York Lords, “Celebration for a People’s Church,” 1969

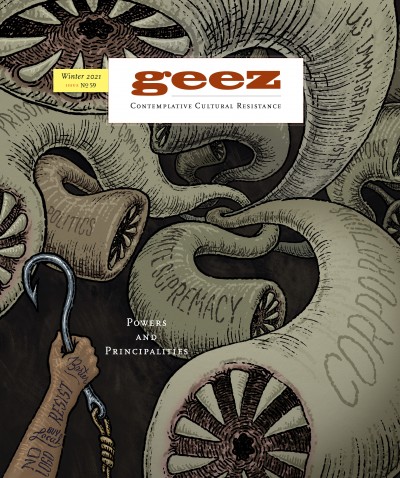

It doesn’t take much historical investigation to find violence, abuse of power, and exclusion in the history of Christianity. Whether we look to the heights of Christian political power as it appears in colonialist violence or the recent trend of white evangelicals mobilizing to support Christo-fascism and white supremacy, it’s clear that the Church has a body count too vast to tally up. How would we, Christians, turn away from this mess and do justice? How can we call out the demonic powers of death and destruction inhabiting our church and craft a new idea of church that serves God and serves people?

Because Christianity has been a motivating, or at least complicit, force in the spirit of death and destruction responsible for so much harm, the answer to casting out the evil in the church might be best found in the margins of the Church itself. Luckily, Christianity has deep margins to consider: for example, The Young Lords, a Puerto Rican street gang turned political organization waging a struggle they called the “Church Offensive.”

The Young Lords were politicized by the struggle against the gentrification of Chicago, Illinois’ Wicker Park and Lincoln Park neighbourhoods in 1968. Puerto Rican families were being forced out of their homes by a coalition of real estate agents and local politicians. In response, neighbourhood Puerto Rican youth, led by Cha-Cha Jimenez, among others, got organized and found militant and creative ways to fight back. The Young Lords Organization started local, but it quickly spread across the country to New York, Philadelphia, Connecticut, New Jersey, Boston, Milwaukee, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico.

To confront the principalities of their neighbourhoods, the Young Lords organized campaigns they called “Offensives,” a name they took from the military movement launched in North Vietnam a year earlier. In Chicago, the Offensives struggled to win resources for their besieged community. The Offensives were dramatic scenes of political action and theatre, and none more dramatic than what the Young Lords called the “Church Offensive,” a campaign that prophetically intervened, both with words and bodies, in Christian institutions.

After their occupation of Chicago’s McCormick Theological Seminary forced the institution to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in low-income housing in 1969, the Young Lords looked for other opportunities to confront Christians with the demands of their own faith. Jimenez and the Young Lords approached Armitage Avenue United Methodist Church, a local church in the Lincoln Park neighbourhood in Chicago, about renting out space in their building to serve breakfast to local youth and other community programs. From the start, negotiations between the Church and the Young Lords were troubled with ideological conflict. The Young Lords were affiliated with Communist struggles, while the congregants were predominately Cuban exiles.

The Young Lords responded by posing their desire to use church space in moral terms. They explained that even though they weren’t explicitly Christians, they wanted to do the work of Jesus by feeding children, providing free child care, establishing a free health clinic, and setting up a liberation school. The Young Lords attempted negotiations with the church in good faith, but eventually the conversation stalled. Ready to get on with their program, the Young Lords seized the church and occupied the space, re-christening the church as “The People’s Church.”

Though parishioners were not pleased, the Young Lords surprisingly found a sympathetic ear in the pastor of the church, Bruce Johnson, and his wife, Eugenia. When police arrived on the scene to forcefully evict the Young Lords, who were ready to resist, Johnson stopped the impending violence by vouching for the Young Lords, explaining that they had permission to be inside the church. Johnson and some of the church’s parishioners decided to throw in with the Young Lords and the People’s Church. Over the next year, The Young Lords would institute the programs they initially proposed, and as a result, the People’s Church became a political foothold in Chicago for radical politics.

But, the People’s Church didn’t last. Despite doing the work of mercy they set out to do, Johnson and the Young Lords suffered sustained political persecution. Later in 1969, Jiminez was incarcerated and put in solitary confinement for his work with the Young Lords. Worse, in September 1969, as Jimenez was in a cell, Bruce and Eugenia Johnson were found brutally murdered in their home – a murder case that remains unsolved to this day.

The Church, as we know it today, is complicit as a tool of racial capitalism, and it won’t just fix itself. The Young Lords’ Church Offensive offers a historical moment when another church was possible – a church that served God and served the people. The powers of death extinguished Chicago’s People’s Church, but that the People’s Church once existed at all is a promissory note that it could always exist again. Just as the Young Lords seized a Methodist church in 1969, perhaps today they might seize our imaginations. To cast out the demonic powers that plague the contemporary church, we can follow the example of the Young Lords – hijacking our own churches and institutions to turn them toward serving the people and doing justice.

Matt Bernico is an independent researcher, journalist, and organizer in the Fight for $15. You can hear more from him on the podcast he co-hosts, The Magnificast.

Start the Discussion