Not Against Flesh and Blood

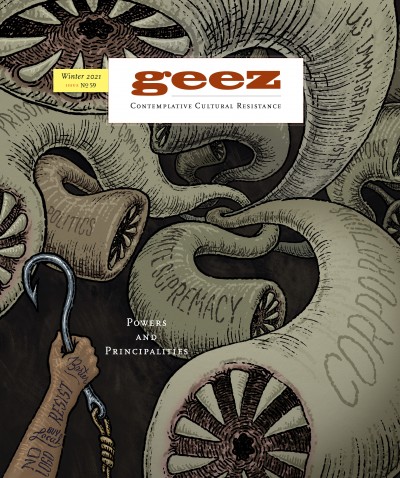

Detail of "Haunted by White Sumpremacy" by Darryl Brown.

The church soon found itself the darling of Constantine. Called on to legitimate the empire, the church abandoned much of its social critique. The Powers were soon divorced from political affairs and made airy spirits who preyed only on individuals. The state was thus freed of one of the most powerful brakes against idolatry . . .

– Walter Wink, Naming the Powers (1984)

When the Roman Emperor Constantine “converted” to Christianity in the 4th century CE, or more aptly when he successfully converted the church to empire, it required a reinterpretation of scripture. For example, New Testament terms related to political forces (rulers of this age, thrones, dominions, authorities, principalities, and powers) almost suddenly came to be read solely as spirits disconnected from corporate, institutional, structural, and indeed imperial realities. Their essential criticism was gutted. Constantine was off the hook. And for centuries the church was denied access to an entire language of social and political critique.

It took various historical crises to refill these terms with meaning. In Europe the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany made these words light up for Christians engaged in resistance. Liberation struggles in Africa and Latin America did something similar. In the U.S. it took the anti-war resistance to the Pentagon’s war-making state on the one hand, and the African American freedom struggle on the other, to bring this language back onto the map of Christian social ethics. In 1967, when Martin Luther King, Jr. identified the “giant triplets” of racism, militarism, and extreme materialism, he was naming the reigning principalities in the United States.

At present, a question hangs in the balance. Will a new generation of Christians actively engaging those same triplets, along with a further set of forces (armed white supremacy, militarized policing, official fascism, and climate catastrophe/environmental injustice), find this biblical terminology useful and illuminating?

In my own twenties, I met William Stringfellow, a “lay theologian,” as he was called, or an “organic” one we might say. From the vantage of the freedom struggle and the anti-war movement, he was among the first in the U.S. (and I’m including here academics, biblical scholars, and certified theologians), to reground the powers and principalities in common reality.

In 1964, he’d published a book, Free in Obedience, which named them as institutions, ideologies, and images. He was just beginning to categorize what would become a detailed and practically endless listing. Think: nation and state, corporations, the law, capitalism, Marxism, neoliberalism, patriarchy, sports, science, career, money, technology, family, white supremacy, even unions, movements, and churches, no less. He found the powers to be legion (check out Mark 5).

I read that book in preparation for hearing him speaking at my college. He sat to talk, frail from a yet-undiagnosed illness. But he spoke with fire in his eyes about the “power” of racism. The Black students, who said they’d never heard a white man talk like this, besieged him after with questions.

Later I learned that he’d begun seriously thinking on the principalities while doing street law in East Harlem. He’d gone to work there after graduating in 1956 from Harvard Law School. Poised for a lucrative practice, he was to all appearances making a bad career move. But from the people of his neighbourhood he heard tell of the powers, particularly in the way they spoke of The Man, or the police, or the welfare bureaucracy, liberal philanthropy, absentee landlords, the mafia – as if they were predatory creatures occupying the neighbourhood and arrayed against Black and Puerto Rican folk. (Here in Detroit, Mama Sandra Simmons just shorthands them as “monsters.”)

All ring a biblical bell: “Our struggle is not with enemies of flesh and blood, but against the rulers, the authorities, against the worldly powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in high places” (see Ephesians 6). And so began Stringfellow’s work of unpacking and regrounding the powers. (His best read is An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land.)

Stringfellow, in turn, became an elder and mentor to me in the ways and the wiles of the principalities.

From early on, he’d been attentive to the creation hymn in the first chapter of Colossians which proclaims the powers good and necessary for human life in society. In such terms, they have a life and integrity of their own, separate or separated from human beings. They are accountable to God in judgment for their vocation, their calling, their purpose to serve life and creation. And like human beings, they are subject to the fall, prone to confusion, distortion, and corruption. Even inversion. Where they are called to praise God and serve human life in creation, they end up presuming to take the place of God, and dehumanizing or enslaving human beings. They become demonic.

White supremacy, though it has ancient and even biblical analogues, is a “modern” principality. Its inception coincides with European capital expansion and “scientific enlightenment.” The latter not only desanctified and disenchanted the world, but sought to “objectively” categorize all of life into biological kingdoms, phylums, and classes – including, by extension, human beings according to race. The “savage races” had been discovered. This was necessary and convenient for the expansion project, the taking of land and the extracting of human labour.

Let us employ white supremacy as an exemplar in understanding the principalities. Subject to the fall, the powers suffer the effects of idolatry. Abetted by human beings they seek to supplant God, the Spirit of Life. They are idols, every one. Full blown, they are anti-Christ, which is to say anti-human. Their work is to capture and dehumanize. Whiteness is such an idol.

Walter Wink, the activist theologian and biblical scholar who wrote a magisterial trilogy on the powers, following Stringfellow’s lead, posited an ethical formula: they must be named, exposed, and engaged (by which he titled the three volumes of his work).

How to engage? Is there a way to withdraw the projection? The alienation of false worship? The New Testament writings do offer a multiplicitous view of powerly “redemption.” They claim in the end, the principalities are unable to separate us from the love of God (Romans 8:38-9), can, in baptism, be “died to” and so be freed from (Colossians 2:20), can be addressed and even evangelized, called back to their authentic vocations (Ephesians 3:10), be met in nonviolent combat of the spirit (Ephesians 6:10f.), be laid bare, made a spectacle, and disarmed (Colossians 2:15), be dethroned, neutralized, and put under subjection (1 Corinthians 15: 25-26; Ephesians 1:20), and be found subject to mortality, doomed (or graced even) to pass away (1 Corinthians 2:6-8).

What can this mean in our present moment for white supremacy? What could possibly be meant by redemption? It seems from its very foundation to be designed to dominate and destroy bodies, communities, and the creatures of Earth. What if white supremacy is simply among those powers doomed to pass away, and soon? What if it is the moment (even late) for this power to die, and for white people to die to it? Die out from under it? Even if doing so feels like being thrown to the ground in convulsions.

We are in a time of deep historical conflict which marks a dangerous and unsettling moment, and which also holds the possibility of real transformation. A young, lifegiving movement has risen up to challenge white supremacy and summon a massive cultural shift. It confronts racism in its blunt and most visible violence: police brutality. Little wonder the powers squeal and rage in backlash against it. They fight for survival and make that their sole and desperate purpose.

White supremacy as a principality is in systemic collusion with other powers. It has insinuated itself in law and policy, in the judicial system and mass incarceration, in the algorithms of data extraction, in systems of access to education, housing, food and water. It’s embedded in the mapping of social and geographic reality. And it has a spiritual grip.

One of Walter Wink’s biblical insights was just this, that the powers have an interiority, an invisible aspect, a spiritual dimension that must be named for them to be seen and recognized. It is the genius of their seduction and grasp. Remember, the legal apparatus of American apartheid, Jim Crow legislation, was repealed, judicially overridden, and legally dismantled. But because white supremacy has this spiritual dimension and capacity, it rises up and reconfigures itself in ever new and more guileful forms.

To disentangle racism from our institutions and from ourselves, requires not just deconstruction, but exorcism if you will. Or nonviolent weapons of the spirit, should you prefer. The churches have been altogether too timid, not only in joining this movement, but in bringing their gifts of discernment and spirit. Consider their tactics of liturgy, prayer, fasting, song, even ancient rites of exorcism. Nonetheless, the movement can be seen to draw on other traditions – African, Indigenous, and hip hop spirituality among them – to build community and engage this power. Music and rhythm, poetry and art, invocation of the ancestors, ceremony and procession are among the strategies for confronting its possessive claims.

The assault on Black bodies and Black lives is obvious. Less clear, perhaps, is the dehumanization that white supremacy wrecks upon white folks. We are deadened, emotionally incapacitated, in perpetual denial, dreading of shame, in bondage to the seductions of ersatz privilege. Dispossession entails confession of complicity in our own bondage. We live in a system of white supremacy, and white supremacy lives in us.

Recent work on race trauma indicates that white supremacy inflicts and encodes itself in our bodies. Differently so in Black, white, and police bodies, bypassing our reason and rationality. (See Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands.) This is a spiritual imprint. Confronting the systemic principality of racism begins with and is inseparable from our own healing and transformation.

Paul’s admonition, even in spiritual warfare, is to nonviolence: our fight is not with flesh and blood, but with the powers. In that sense, the enemy is not the racists, ourselves or others, but the racism itself.

Mr. Trump has been a pitiful victim, utterly dehumanized. He conjured and nourished, bid and unleashed white supremacy in a true collusion with his campaign. He armed, signaled, and marshalled it. But in fact, it used him in its latest rise. Wrapped him around its finger. Worked its dehumanizing way.

We have not yet come through the chaos which in him the powers have unbridled. He, with us all, will be living in it for Who Knows how long. The Biden/Harris election does not signal victory, but only the new moment and fronts for dethroning, de-spiriting, and dismantling white supremacy. And for keeping at the beloved community.

Bill Wylie-Kellermann is a nonviolent community activist, retired pastor, and author – most recently of Principalities in Particular: A Practical Theology of the Powers that Be . He lives in Detroit, Michigan.

Start the Discussion