The Disobedient Body

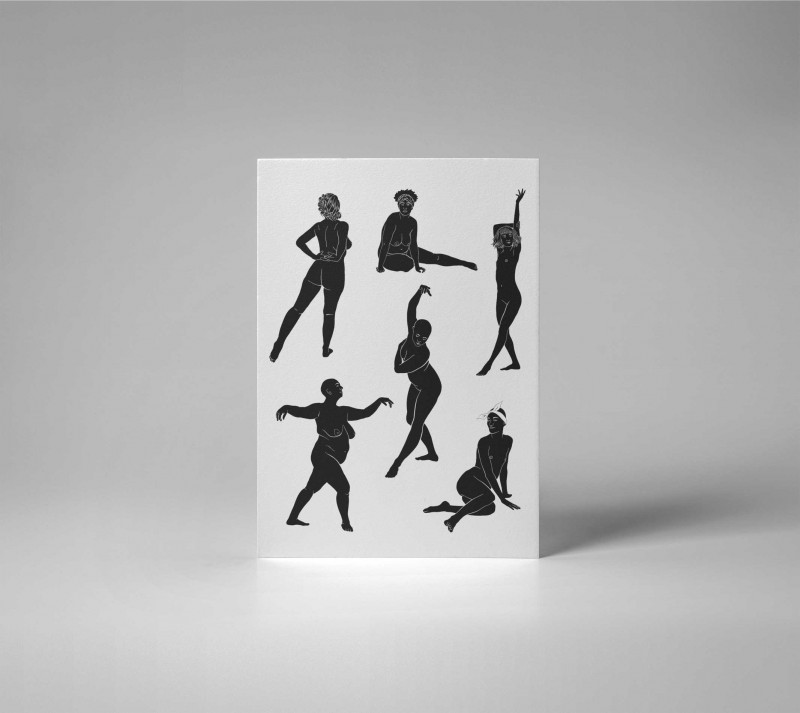

curvas de verdad Credit: Jessie Hernandez Klein

In a time when people protest via hashtags and newsfeeds, does putting your body on the line still say something?

This question is important because electronic communication really has, in my lifetime, changed the nature of activism. As someone who is both old and an early adopter, I remember when we first established electronic communication between the resistance in East Timor and the solidarity movement overseas, and my realization in that moment that everything was going to change. Electronic activism is not only about generating hashtags or signatures on Change.org petitions. It includes powerful actions of uncovering and sharing truth, and also has the possibility to create at least as much disruption as physical acts of civil disobedience. One well-executed distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) can shut down as much activity as dozens of blockades.

And yet there is still something about the body. Mario Savio’s 1964 demand that we throw our “bodies on the gears of the machine” is still resonant. So many of the movements which have moved societies towards justice have depended almost wholly on bodies and presence: the Madres of the Plaza de Mayo, the Women in Black, the unarmed crowds which surrounded government buildings in Prague or Belgrade or Jakarta and forced dictators down. The disobedient body, the body which insists on being present and visible in ways which power would deny, is still, perhaps, the primary vehicle of justice.

For we are our bodies. We are only fully present as bodies, marked by sex and gender and race and disability, displaying our relationships to power and privilege, and at the same time unique, specific, identifiable, and irreplaceable. The body says: Here. Now. I am. The body says I am in the way. I am unavoidable. I am the person who says no.

Power and economics, abstract as they may be made to seem, are finally about the fate of bodies – which bodies may be subjected to violence, which bodies may be deprived of good food or adequate shelter, which bodies may be protected from fire and flood, which bodies can be compelled to work under punishing conditions for the profit of others, which bodies may be allowed choices about sexuality or reproduction, which bodies are to be controlled, which bodies may be bought or sold or imprisoned, which bodies may be subjected to catastrophic climate events, which bodies are permissible to kill, and which are not. Capitalism would prefer to abstract us from these basic realities but they are the bedrock of all our systems. If justice is about reclaiming the right of each body to a decent life, then it must be bodies making that demand.

The body is the resource available to us all: those who lack access to the electronic world or the skills needed to use it subversively, those of us with no particular gifts but humanity and existence, those who cannot or choose not to speak. In fact, it is often the most despised bodies whose simple presence can be the most disruptive. It is the bodies that are not allowed into public space whose eruption into visibility can upend power relationships. It is silent presence that can speak the loudest.

The bodies, often showing the visible damage of illness, spread out on the street in ACT UP die-ins during the worst of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the developed world. The bodies of the Idle No More round dancers in shopping malls throughout the territory we call Canada. The bodies of Indigenous women and elders at the Wet’suwet’en blockade, making visible, in their presence, their unextinguished claim to the land of their ancestors. These are loud bodies.

I write this as a Christian – and as such, I also understand the body to be the crucial site of our relationship with God. The core doctrine of Christianity insists that God chose to be in a body, and the whole of the story is a story of bodies and material stuff. One of mud, blood, and spit, of tears and hair, of dried fish and broiled fish, of bread and water and wine. A story of a human body in the hands of power, beaten and mocked and nailed to a piece of wood, and yet still more in control of the story than all the tormentors. The story of how our human bodies are called to continue the work.

The Incarnation means, if it means anything at all, that the suffering of any creature’s body is a part of the suffering of Christ, and that bodies in resistance, stepping forward for love and justice, are part of the resurrection. In my own Anglo-Catholic tradition, our practices of worship are intended to reconnect us with our bodies and their appropriate acts and habits. They remind us of the importance of movement in community, human voices joined, basic food shared equally, and the recognition of mutual vulnerability. Properly understood and carried out, it is a powerful political pedagogy.

And it can work the other way around as well. For some years I found it impossible to attend church. It was also during those years that I found my own way of participating in the Incarnation. It was the liturgy of protest; the discipline of nonviolent civil disobedience; the type of affinity group structure developed by the Clamshell Alliance, with its demands for listening and attention; the inward locus of meditative control required by commitment to nonviolent action; the individual and coordinated structured movement with other bodies; the placing of the physical self at the centre of intersecting axis of power; the patience required in the process of arrest and imprisonment; which was my way of honouring and enacting the Body of Christ.

I do not intend to claim unique value for any one form of activism. Any campaign is likely to be successful if it includes action in multiple styles, pressure from multiple directions, and is carried out by different people according to their own gifts and beliefs. It is also true that any or all of our attempts may fail, and there is no failsafe tactic for creating greater justice. No kind of action, at this stage, can spare us serious, maybe more than serious, effects of climate change. But within that larger picture, bodies gathered in nonviolent resistance can still, at times, say the things which need to be said, stop the gears for at least a moment, and also perhaps help to form us into the kind of persons, the kind of community, which may persist.

Maggie Helwig is an author, activist, and rector of the Church of St Stephen-in-the-Fields (Anglican) in Toronto, Canada.

Photo credit: Jessie Hernandez Klein, “curvas de verdad,” April 2019, Digital illustration.

Start the Discussion