Sexuality like a Boulder: A Testament to William Stringfellow

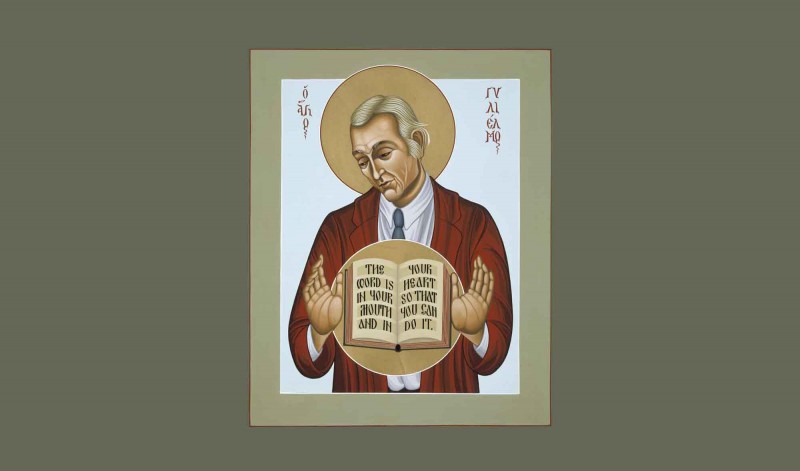

“William Stringfellow Keeper of the Word,” William H McNichols © frbillmcnichols-sacredimages.com, Acrylic on Wood.

The first time I remember “thinking theologically,” as in a light going on, was in high school reading Instead of Death (1963) by William Stringfellow. A little study book for young people, it set forth chapters on death, identity, vocation, work, loneliness, and yep, sex. First time I heard tell of the principalities. He declined to “talk down” to his young readers.

Stringfellow was frank in the paradoxes, if not ironies, of his theology. The search for self in sexuality was a frantic and futile path, destructive to oneself and others; yet, in Christ or by grace, sexuality was a realm in which a fullness of freedom, delight in one’s humanity, love, and even sacrament could be recognized. Good news.

He eventually became to me a mentor and friend, the subject of biographical research and reflection. In consequence, I’ve since come to re-read the book with an eye to his own life.

For example, he identifies himself there as vocationally celibate – in relation to any notion of “Christian marriage.” He lived in resistance to the principality of white, middle class, American family. He was, in fact, a gay man – which could be said to amount nearly to the same thing.

In Instead of Death he addresses homosexuality directly – a topic otherwise absent on the bookshelf of our church youth fellowship room. By then he’d served as general counsel for the George Henry Foundation, defending gay men, including his East Harlem clients, from prosecution, so he named the legal jeopardies involved. But for those living through the decades prior, his main concerns were pastoral: the temptations to suicide, desperate identity crises, falling victim to surveillance, extortion, blackmail, fear of exposure and social disgrace, unabsolved shame, collapse of family relationships, and despite lots of sex – perhaps never finding love.

One chapter appeared previously in The Christian Century. It concerned loneliness and may actually have been the most existentially personal of the book. Loneliness is described in excruciating detail, setting forth a list of the fruitless remedies to which humans turn for relief, including work, marriage, suicide, but also alcohol and sex. In the period prior, his own life had become somewhat dissolute, drinking heavily (or as he later put it, enthusiastically) and indulging one-night stands often arranged at the public baths.

But then, he met Anthony Towne who was bartending a party for the president of the World Council of Churches. Anthony requested Bill’s help in preventing an eviction he was facing, but Stringfellow neglected the commitment. On the day appointed, Anthony appeared at his door and Bill did the honourable thing: invited him to move in. A temporary arrangement became permanent. Became love. Became self-acceptance. As he would then write in Instead of Death, “Count your loneliness a means of grace . . . Love yourself and then your love of others will be neither suicidal nor destructive, neither jealous nor possessive . . . And when you love others – tell them so – celebrate it – not only by some words but by your life toward them and toward the whole of the world.”

Shortly they would move to a seedy penthouse on 79th Street with a vegetable garden and rabbits on the roof, plus a single bedroom with French doors. It became a churchly destination, the scene of movement fundraisers, and not a few parties. Though his work and reputation were flourishing, it was taking a toll on Bill’s health. By 1968, he finally quit alcohol, survived radical surgery, and moved with Anthony to Block Island – then a working-class community off the coast of Rhode Island.

When Anthony died suddenly in 1980, Stringfellow produced his most beautifully written book, A Simplicity of Faith, recounting intimately his experience in mourning. Grief is a form of love, and the book is a love tome – for Anthony, for the Island itself, and for the community who had accepted them. In the course of things, he variously describes Anthony as his “conscience” and his “sweet companion of seventeen years.” His copy editor, a dear friend on the Island, sat by his fireplace with the manuscript in her lap and asked, “Oh Bill, why don’t you just come out and say it?”

On the other hand, Daniel Berrigan commenting on a manuscript of mine, urged me to consider the economy and tact of Simplicity. Less is more, he said. The book was like a boulder, mostly buried, where enough is told but the rest is pure depth, understood because heard anyway. Like the love beneath this book, filling it. As Adrienne Rich writes:

ilence is not always or necessarily oppressive, it is not always or necessarily a denial or extinguishing of some reality. It can be fertilizing, it can bathe the imagination, it can, as in great open spaces . . . be the nimbus of a way of life, a condition of vision.

– Arts of the Possible

Some who knew him well described Stringfellow as “almost not out.” A wide circle of close friends would say, “Of course he was out. He and Anthony lived together as partners in practically everything.” Another friend, equally close, told me, “I don’t buy it.”

In the book, Bill speaks of Towne’s vocation being “in principle, monastic, as is my own. (That is the explanation of our relationship.)”

In “The Block Island Two” about Stringfellow and Towne on outhistory.org, Heather White considers the vocational matter. “These layered allusions to Christian monasticism convey through suggestive hints – rather than by direct persuasion – that Stringfellow’s profound intimacy with another man was brotherly and spiritual and thus completely platonic . . . Their life together is not merely a case study of the mid-century closet; it also shows how Christian traditions of spiritual brotherhood could continue to shelter same-sex love from social scrutiny.”

Fair enough. But to be clear, Stringfellow would count monastic community not as cover or closet, but truly vocational. Denied marriage, and painfully so, their monastic commitment was a common vocation. In Stringfellow’s theology, identity is a vocational matter: who one is called in the Word of God to be.

To several friends, Stringfellow identified his first love, in fact his first sexual encounter, as occurring with “another fellow,” at a Student Christian Movement conference during college. This first love was also entangled thoroughly with faith and his sense of radical freedom in the gospel. In one account he even conveyed it as a kind of conversion experience. Emotionally and with tears in his eyes, he told of a weekend they spent holding one another as they read aloud from the New Testament, discussing it in one another’s arms.

In those same college years, Stringfellow had invited Bayard Rustin to campus for a “Political Emphasis Week” of his own invention. Rustin was to be a central figure of the Freedom Struggle who determined that he needed to come out as a homosexual, for the sake of both integrity and movement. He was a nonviolent mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Though for a time it distanced itself from him over being out gay, he was eventually re-embraced to become the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. Rustin was the epitome of intersectionality, of courageous out-being, for which he paid a price. A price he expected others to freely pay.

A contemporary, Stringfellow never self-identified in publication or public pronouncement, even when he was addressing the topic, otherwise straightforwardly.

In 1965, he gave an address at the Hartford Cathedral, but first to the Mattachine Society, the first gay organization in the U.S., consciously laying the group infrastructure and groundwork for movement. Among his comments:

Can a homosexual be a Christian? Yes, if his sexuality is not an idol . . . For all varieties and forms of sex, for Christians, integrity lies in that which honours the gift of life which God has bestowed on each and every person. Sexuality is part of that gift, though it is never the fullness of that gift. Sex is a mundane symbol of that gift: a means by which that gift is proclaimed and celebrated . . . that [human beings] are called to love and affirm and help each other in the face of death . . . In that sense, from a Christian point of view, sex is good. There is, in other words, no fear in love. In fact, love casts out fear.

Can Stringfellow be looked to for wisdom, in this present moment? He was, to be sure, convinced that “the prominence of the sexual identity of a person was highly overrated.” He insisted that sexuality not be an idol, not be a source of “justification” (in the biblical sense – it was that which would entangle it with sin). He spoke publicly on these matters as if he could do so, without placing his own sexual location on the table. He wrote of his love for Anthony Towne while insisting, through rhetorical indirectness, that their partnership not be reduced to or subsumed under sexuality.

At the same time, I would argue that his embrace of same-sex love deeply affected his life and theology. It was an early choice and move to the margin, joining the outcasts among whom Jesus walked and ministered, which enabled seeing the world as outsider, from below, with others marginalized. Hence his bad career moves of going from Harvard Law to East Harlem, or reading U.S. empire as Babylon, or embracing his status as race traitor to white supremacy. The margins did intersect.

I’ve struggled to sort all this through, even the wisdom of writing it. I want to honour his vocation and his choices in context, but also bring his gifts to bear in an era of identity politics and the intersectional organizing to which I am myself committed. Since Bill’s death, advances in rights and protections by law, gains now so under attack, have been secured by a queer movement for which the politics of identity and risk were clear and necessary. I have no doubt he smiles in gratitude.

Bill Wylie-Kellermann is a nonviolent community activist, pastor, teacher, and author residing in Detroit, Michigan/Waawiyatanong. He has at least two books on William Stringfellow: A Keeper of the Word (Eerdmans, 1994) and William Stringfellow: Essential Writings .

Start the Discussion