Parenting Kids to Live in This Broken, Hopeful World

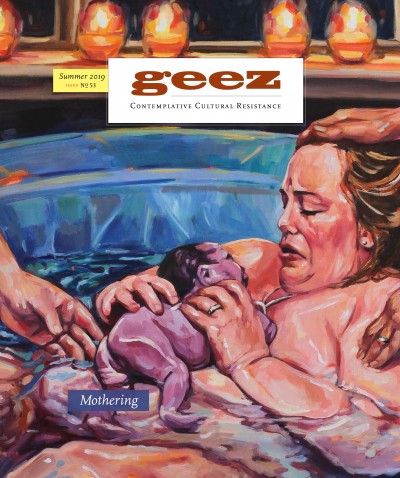

"Lotus" Credit: Amanda Greavette, 2017 (link below)

When it comes to living out intentional, countercultural values, my life partner and I sometimes viewed parenting as the great compromise.

Seen through lenses that have not yet crossed that life-changing threshold, parenting seemed like the pivotal turn that made people committed to social change suddenly choose different, safer, or more homogeneous neighborhoods; big houses; more convenient, packaged foods; better school districts; gas-guzzling large vehicles; and endless screen entertainments. It also appeared to blunt the prophetic edge. Parents were too exhausted or routine-bound to show up at demonstrations, too tired to read, and too hard to have “real” conversations with. Choosing to raise a child in consumptive North America in a time of environmental crisis was also not an easy decision.

So it was rather late (at age 40) – and with a shade of concern – that we had our own kids. How much would they change the shape of our lives? We’d lived for almost fifteen years in pretty urban realities. Would we leave our low-income, urban neighborhood where gunshots and police cars are not unusual, and where our kids would live as a racial minority? My son was less than five months old when my pediatrician asked us where we planned to send him to school.

The experience of parenting runs deeper than issues and political commitments. Parenting teaches us the immensity of love, forgiveness, our own inner work, patience, and joy. It is a path full of spiritual lessons, some of them much deeper and soul shifting than where we choose to live and go to school. In fact, my entire perspective in this article assumes some space of parental choice, which is what most parents do not necessarily have.

Our parenting is as affected by social location as every other part of our lives. I parent from a particular place – educated, a middle-class background, white with racial privilege, and more than adequate income to cover basic housing, transportation, and food. My musings are probably irrelevant to the majority of the world’s parents who are not in that particular group. But if you are in that tribe, you may resonate with my struggles.

Parenting can be our excuse not to make hard choices – which are also transformative – for ourselves or our family. If I want to raise children who want to build a more just, transformed world, they must begin to understand these choices require having skin in the game. If we believe in combatting racism, we need to live in spaces that challenge our racial conditioning. If we want to turn our planet’s environmental trajectory and live more sustainably, we will have to model a very different, non-consumptive and less carbon-dependent life. If we want to build human community and interaction, we will need to be wise as serpents in the use and abstinence from our screen devices.

It is all too easy to talk to our children about such values while living basically comfortable lives that keep most of our economic, racial, and educational privileges intact. We can raise them knowing that racism is bad, but still keep them in what my kids refer to as PWIs (Primarily White Institutions). We can teach them the planet is suffering so that they recycle, without living in more hard-core ways that actually begin to alter the patterns of human consumption.

It is important to share with our children our choices and why we make them. This is very hard when children are young, but if parents consistently own our choices and explain them at age-appropriate levels, kids grow up with the sense that they are operating in a world that is larger than their own circle and which has needs beyond their immediate gratification.

For me, it was critical that my kids felt my love, realized l wanted to spend time with them, and grasped that our rich, full life depended on quality relationships and experiences as opposed to material things. It was important that I not pass on a purchase or experience by dismissively saying that it “cost too much.” While that was sometimes true, it was also a convenient shorthand for a larger worldview in which we didn’t choose to spend our resources in that way, or we had limited resources because of the good work we chose to do. Your kids need to know what you value. When I didn’t explain this, my kids thought we were poor and would focus on getting rich to get those things we denied them. But when they understood we were making certain choices, it was a different ballgame.

Sharing these realities can make the world heavy for kids, but most children grow up in heavy worlds. Learning to carry the world is a part of maturing. When I was growing up in South Carolina in the sixties, my loving, white parents made a pivotal decision which they believed was for my own good. They shielded me from news of the civil-rights movement – one of the most powerful social change movements ever in this country – because they wanted to protect me from turmoil and unrest. When I, at age nine, heard on the school bus that Dr. Martin Luther King had been shot, I didn’t know who he was. I did have a beautiful, rural childhood, but to me, the fact that it left me completely ignorant of such a powerful movement unfolding in my backyard, a movement which touched many people I knew, is haunting. What else do I not now see in my bubble of protected comfort?

It is critical and inevitable that our children engage the world. To help them do that while you are there with them and helping them process it is important. Yet we must also be prepared for the time (usually ages twelve until at least twenty) they begin to challenge your values and the interpretation of the world you handed them.

At some point in these years, you realize that your kids are on their own journey. Not only is it impossible to have them clone your perspectives, but it would also be a great disservice to them. For both of my kids, this led to a period where they were lashing back at the choices we had made for them. My daughter desperately wanted to move to the suburbs. My son was embarrassed by our small house, shabby neighborhood, and total lack of fashion. Both wanted to play computer games and have phones and found our screen prohibitions ridiculous and mortifying in front of friends. My daughter’s insightful line was: “Just because you are deciding to live poor does not help poor people in other parts of the world so there’s no point to it!”

At this juncture my son, two years older, told her: “Don’t worry. In two years, you will agree with Mom and Dad. I went through that angsty place too!” And to my utter shock, he turned out to be right. In a few years, she couldn’t imagine living in the suburbs.

At this stage, when peer pressure is at its height, it is appropriate to make some compromises, especially if the likely outcome of resisting compromise is that your kid will be ostracized over the long haul. Kidding is endurable. Extended social isolation is not. I found that when our children understood the “why” of our choices, they were empowered to explain them. This made them somewhat proud that our family was different even when they realized that their friends just found it a little weird.

Ultimately, your children will forge their own path, and it is just as likely to be different from your own as it is to be similar. You must begin releasing them to their own choices. Now that my son is a college sophomore and my daughter a rising senior in high school, we reflect on what they might have had us do differently as parents. They have some insights for me.

“You raised us in the city, yet sometimes you almost chide us for being city kids. I just feel that is healthy, immersive. It shows that we had a good experience,” comments my daughter. “On the other hand, if I do mainstream about some lifestyle issues – fashion or makeup or shopping – this does not mean anything went wrong. It does not mean I am trying to conform, or that I have released all the values you raised me with.”

My son reminds me that if parents try to control too much, their kids may mature with little ability to self-regulate and discipline themselves. “I liked your parenting. You were pretty understanding of my buying clothing and sneakers, though you disagreed. I see fashion as artistic and it’s important in Philly and the neighborhood. You gave me your critique, but eventually gave in, and I am grateful.

“Screen stuff was harder. Screens are entrenched in today’s world and my own vocation as a film-maker. There might have been ways to be healthier about them. You were too hard-core, too dismissive of all screens. I find that today I am not good at self-regulation because I was not exposed to that discipline of balance with screens.”

To parent is to spend entire days making choices about how to respond to one’s child. There are many spaces for grace. Ultimately, we need to love both our children and this world – passionately. That is the truthful place from which we begin.

Dee Dee Risher lives in Philadelphia in the Vine and Fig Tree Community. Many other honest struggles around parenting are described in her recent book, The Soulmaking Room (Upper Room Books, 2016). She has written an entire book of poems about her grandmother, a farm wife, who shaped Dee Dee by her primal love of nature. She taught Dee Dee the names of hundreds of shells, flowers, birds, and plants, and she stuck reminders of natural beauty all over the eclectic farmhouse her grandfather built – then rebuilt when it burned to the ground only a few months later.

Image credit: Amanda Greavette, “Lotus,” 2017, oil on canvas, 16×20”, The Birth Project.

Start the Discussion